Wales Arts Review brings you part one of Nerys Williams‘ captivating memorial lecture from the Estyn yn Ddistaw/ Holy Glimmers of Goodbyes: A Day of Reflection on the Poetry of War and Peace in Wales organised by Literature Wales and held at the National Assembly for Wales in February of this year. Williams examines how Welsh and American war poetry represents conflict, space, and ideas of home, and reaches from World War One to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. This article features the famous Welsh poet Hedd Wyn who died at war before being able to accept his Eisteddfod Award.

How do we locate war poetry? Where exactly does war poetry ‘live’ and where can one find it? In attempting to answer these questions we might want to consider war poetry’s relationship to ideas of ‘home’; how war poetry offers a reimagining of what home might be. Perhaps, a more fundamental question might be how does war impact our everyday landscape and how does that change our perception of home? In attempting to address these aspects of war poetry, with particular attention to the work of Welsh poets including Hedd Wyn, I will map the shift from ‘soldier’ or WW1 poetry to more recent war poetry, associated with conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But to begin, I want to begin to offer a perspective on that more intractable question, where might war be found, and its impact on our everyday landscape, by turning to visual art from West Wales. Osi Rhys Osmond’s late paintings offer a complex negotiating of how ideas of home are inscribed by war. A series entitled Hawk and Helicopter (2011) shows us how the aerial space of Carmarthen Bay is inhabited by Chinook helicopters. In Osmond’s paintings, hawks and sea birds share the sky with military hardware. The catalogue for the original exhibition at Swansea’s Mission Gallery describes the series of paintings as ‘an account by drawing, painting and text of the artist’s experiences, thoughts and observations’ which was created ‘while watching and painting the sunset from a high point facing south-west, overlooking Carmarthen Bay.’ The exhibition notes remind us that the Bay is ‘designated as a Special Area of Conservation, as well as housing a military testing ground on its estuary edge.’

One of the most startling of the series is Osmond’s ‘Chinook’ painting. This work depicts a low-lying sun and a seascape which is overwhelmed by a graphic rendition of a precariously tilted military helicopter. The helicopter’s flight pattern is placed in parallel with a seabird’s. Following Osmond’s death, the painting was presented as a gift from the people of Wales, to the Flemish Parliament at the Senedd Cardiff, on November 16th 2017. In his notes for the original exhibition, Osmond evocatively described the processes of mediating a landscape that is intruded upon by the activity of the MOD operations from Pendine and Aberporth. Capturing the wildlife of Carmarthen Bay on canvas required intense observation. Periods of meditation were routinely disrupted by the military test runs in the sky:

Vast flocks of wading birds, migrants and residents congregate, roost, feed, preen, hunt and breed. Foxes prowl shorelines and rabbits tumble in cliff top warrens. Mad hares strut high fields. Cormorants guano their red roosting rocks a rancid pink. Ravens clank and tumble, blackly. The rivers pour down as the moon drawn tide ebbs and flows. This is the normality of the place. Occasionally, this is disturbed by unexpected sights and strange sounds, for here hawks hunt and sometimes helicopters hover; peregrine falcons and Chinooks appear and disappear, fly, rise, descend, hunt, patrol, attack and retreat. The sudden raucous voice of the Chinook bruises the sky, assaults hearing, the blade’s violent clatter shatters the clear estuarine light.

War poetry has always offered a complex perspective on how war intersects with ideas of home and belonging, as well as the relationship of travel and mobility. I will argue that the superimposition of war upon the landscape of home becomes increasingly more apparent in recent poetry of 21st Century Wales and America.

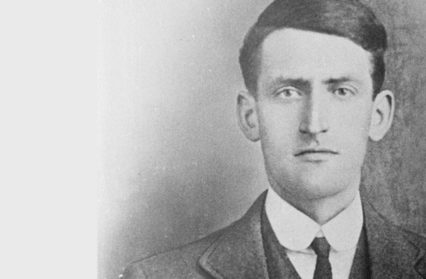

GWILYM WILLIAMS (PENYBONT, CARMARTHENSHIRE) WW1

Commemorating a war poet in the Everyday

In a small village in West Wales, a commemorative black stone cross sits on the brow of the hill, near a chapel in a small village in Carmarthenshire. The scene is replicated in hundreds of other villages in Wales. This memorial in the village of Pen-y-Bont near Trelech is fenced off and accessible only through a small latch gate. Children after Sunday school would dare each other to walk around it, braving the sheer drop. The cross commemorates the loss of three local men in WW1: Pte David Harries, Pte David Davies and 2nd Lieut Gwilym Williams. Williams was from the local farm Nant-yr-Afr, a graduate of the Department of Welsh, Aberystwyth and a promising poet. He won numerous Eisteddfodic chairs, including the Chair of the University Eisteddfod in 1912, his winning ode was entitled ‘Gwanwyn Bywyd’ (‘Springtime of Life’).

After graduation, Williams taught at Newtown and Walsall near Birmingham. In July 1915 he joined the army and was made a lieutenant in the 17th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. In May 1916 Gwilym was in Fauquissart. He was injured by a bullet on 20th May and died the following day in the hospital at Merville. Williams was buried at Merville Cemetery on 22nd May 1916. He was twenty-six years old.

Not unlike Hedd Wyn (Ellis Evans), following Williams’s death, his poetry was collected and published in a volume, edited by his brother John Williams. This overlooked volume Dan Yr Helyg/Under the Willows (1917) contains englynion, lyrics and longer work or pryddest as well as essays. A long, and sadly, unfinished work by Williams, Gwladgawrch (Patriotism) finds correspondence between Belgium and Wales. The poet in the excerpts below presents a relationship between Belgium’s battle for survival and freedom and Wales’s dream of political self-determination. The space of home and battlefield are in close dialogue with one another:

Gwell nag anrheg aur y treisiwr

Ydoedd rhyddid ganddi hi,

Dyna bechod Belgium fechan,

Dyna’i bythol fri.Mae cynhaeaf arall weithion,

Ar dy feysydd Belgium brudd,

A pheiriannau Mawrth yn rhuo–

‘N lladd bob nos, bob dyddGwell nag anrheg ydoedd rhyddid

gan ei dewrion gwladgar hi.

Dyna cododd gwrando Cymru

I anfarwol fri.Better than a violator’s bribe

is Belgium’s idea of the free.

Through her resistance

valour and honour we see.There’s another harvest moving

Belgium fields, a broken might,

war machines are roaring

killing day and night.Better than treasure was freedom

of her patriots countrywide

Wales listened with attention

Honouring Belgium’s pride.

(Translation by Nerys Williams)

In Williams’ poetry, there is a distinct sense of longing for y filltir sgwar, the local community and landscape is presented as a space of solace in his poetry. The world war is outside this idealised space, remote even. Williams was influenced by the Romantics and in particular the nature poetry of Wordsworth. The poetry of Under the Willowsconfigures an unviolated Welsh landscape, a space of retreat and healing. In an essay included in the volume ‘Natur Fel Cyfrwng Diwylliant’ (‘Nature as a form of Culture’) Williams emphasises how the living world offers not only a mental haven but also a mentorship in humility, wisdom and altruism. Here is a translated extract from ‘Nature as a Form of Culture’:

Nature teaches us not only knowledge but wisdom. While pride is associated with the attainment of knowledge, the key trait of wisdom is humility. Humanity need both to be safe and strong… If one searches for a range and intensity of the soul, if one desires to grow in empathy, self-sacrifice, if one seeks for humanity a sense of depth and inclusiveness, one must take Nature as an instructor. (Trans. NW)

HEDD WYN (Ellis Evans): Poetry and Community

Hedd Wyn (Ellis Evans) is often seen as a pastoral poet, having written his memorial volume Cerddi’r Bugail (The Shepherd’s Lyrics) in 1918. Evans grew up with poetry acting as a communal function, not only in local and national eisteddfodau and religious culture but also in commemorative events such as birthdays and weddings. As the war asserted itself, he found himself writing elegies by request for the families in Trawsfynydd and the surrounding area. These poems offered gestures of empathy and mourning. Formally the poems would often be englynion, a four-lined cynghanedd measured verse. In these slight and metrically intricate poems, we find Evans trying to negotiate a bardic tradition with very modern war.

I would also argue that he is knowingly using the traditions of Welsh culture to interrogate a ‘new’ tradition of modern militarism. We can sense a growing of encrypted weariness in these works. As a poet he was in a difficult position, having to write elegies that somehow offered some solace to the families.

One of Hedd Wyn’s most well-known elegies ‘Marw Oddi Cartref ‘/ ‘Dying Far from Home’ was for Corporal Robert Hughes, Fronwynion, Trawsfynydd. Hughes did not die on the field, but in Alesbury camp, he had married a couple of weeks earlier. This poem was in fact a newspaper poem published on January 29th1916 in the Rhedegydd. In this poem we can see Hedd Wyn’s anger at the ceaseless and incomprehensible loss of life, the displacement of a Welsh soldier, uprooted from a nurturing community and the loss of hope. The poem reflects on the industrialisation of death through a mass killing machine. Importantly it also issues its own challenge to any ambition of monumentality. One might think of Siegfried Sassoon’s own riposte to commemorative memorialisation in the poem ‘On Passing the New Menin Gate’ (‘this sepulchre of crime’). Evans equally seeks no grandiose edifices, instead, he suggests that nature should command and reclaim the graves of the dead.

Marw Oddi Cartref (excerpted)

Mae beddrod ei fam yn Nhrawsfynydd,

Cynefin y gwynt a’r glaw,

Ac yntau ynghwsg ar obennydd

Ym mynwent yr estron draw.

Bu farw a’r byd yn ei drafferth

Yng nghanol y rhyfel mawr:

Bu farw mor ifanc a phrydferth

A chwmwl yn nwylo’r wawr.Ni ddaw gyda’r hafau melynion

Byth mwy i’w ardal am dro;

Cans mynwent sy’n nhiroedd yr estron

Ac yntau ynghwsg yn ei gro.Ac weithian yn erw y marw

Caed yntau huno mewn hedd;

Boed adain y nef dros ei weddw,

A dail a rhos dros ei feddDying Far From Home

Trawsfynydd, his mother’s burial ground

Home of wind and rain.

He is asleep- a pillow – a mound

A graveyard of unknown terrain.The maelstrom world- in it he died

buried in the Great War.

Dying so young, and wide eyed,

a cloud held in dawn’s early tor.No more summer’s bright band

No more walking’s digression –

Only this grave, in unfamiliar land

Body curled in earth’s rotationAnd somehow in this dead acre

Let him find a form of peace.

His widow shielded – Heaven’s maker

Heath and leaves cover his grave’s lease.

(Translated by Nerys Williams)

Francis Ledwidge The Spaces of Commemoration (from Pastoral Poet to War Poet)

In Ireland, Ellis Evans is known as the poet who was killed on the same day as Francis Ledwidge (whereas the reverse is of course true in Wales). Both poets died on the same day on 31st July in Flanders in 1917 a few hundred yards from one another. Ledwidge served in three theatres of war Gallipoli, Macedonia and Flanders/Western front. His first volume, Songs of the Fields (1915) was a pastoral hymn to his hometown, Slane, in the Boyne Valley and is an exploration of love and nature. This first volume also includes a cycle of poems that owed their existence to Irish mythology. Like Hedd Wyn there is a keen sense of the botanist’s eye in his poetry and a rooted sense of belonging, class and community.

Ledwidge did not often deviate from the pastoral. Hence the reference to him as ‘the poet of the Blackbirds’, a name derived from some of his most famous early poems ‘Behind the Closed Eye’ and ‘The Blackbird’. Even his love and war poetry contains significant elements of landscape and the bucolic. His two posthumous volumes, Songs of Peace (1917) and Last Songs (1918) were edited by Lord Dunsany, his patron. In these volumes, he did address more directly elements of warfare. His subject matter was often, albeit obliquely, reflections on a global war.

One of Ledwidge’s most famous late poems ‘Soliloquy’ went through conservative editing for its posthumous publication. In effect, this war poem was gelded by its editor. The removal of the poem’s final line changed the context and politics of the poem, as well as the reputation of the poet. Thankfully, the final acidic line (placed in italics below) has been reinstated recently and inscribed in the monument to Ledwidge in Artillery Wood, Ypres. Its re-inclusion grants the poem and poet’s voice a fierce agency:

And now I’m drinking wine in France,

The helpless child of circumstance.

To-morrow will be loud with war,

How will I be accounted for?

It is too late now to retrieve

A fallen dream, too late to grieve

A name unmade, but not too late

To thank the gods for what is great;

A keen-edged sword, a soldier’s heart,

Is greater than a poet’s art.

And greater than a poet’s fame

A little grave that has no name.Whence honour turns away in shame

Next week in Part Two of Nerys Williams‘ exploration into the form, she asks, Where is Welsh War Poetry?