In the lead-up to the American presidential election, Caragh Medlicott delves into QAnon, a conspiracy theory which casts Donald Trump as a ‘hero’, and reveals the risks such ‘fringe’ conspiracy theories pose to the world.

In the age of anonymous messaging boards and far-right chat forums, conspiracy theories spread like weeds on a disused lawn. When coronavirus swept the world, it seemed inevitable that virus-deniers and conspiracy theorists would see something darker lurking beneath the anxiety-rich surface of a deadly pandemic. It’s almost surprising that this year’s headline conspiracy theory is not overtly covid-related, yet there’s no denying that the isolating effects of the virus’ contagion have provided a rich breeding ground for one particular theory’s virulent spread.

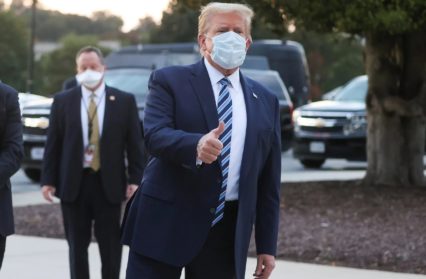

You might have heard of QAnon, but if you haven’t you’ve likely still encountered rumblings of its key tenets: paedophile rings, satanic worship and blood-drinking. This far-reaching, baseless conspiracy theory certainly draws on old tropes, but here it casts an unlikely hero in Donald Trump (QAnon supporters believe Trump was appointed president to save the world). Though the theory has reached a fever pitch this year, it first raised its head three years ago.

Like many a conspiracy theory, it all began with 4Chan – the anonymous imageboard site with a reputation for far-right alignment. In October 2017, an incognito user began sharing a series of posts claiming to have a high-level of US security clearance, each post was signed off ‘Q’ (these posts would later become known as ‘Q drops’). Each of Q’s messages purported insider knowledge regarding a global cabal of powerful sex traffickers. The posts are written cryptically, like a comic book pastiche of what top-secret reports might sound like.

QAnon bears some resemblance to 2016’s Pizzagate theory, a conspiracy that interpreted leaked emails between Hilary Clinton and her campaign manager John Podesta as coded messages revealing a Democrat-run human trafficking ring fronted by food chains. Pizzagate didn’t drum up the same attention that QAnon has received since, but it still culminated in a man from North Carolina opening fire on a pizzeria in Washington D.C.

Hilary Clinton was one of the key villains in the Pizzagate theory, and she – along with a number of other high-ranking Democrats – is a baddie for QAnon followers too. Other supposed deep state insiders include typical suspects like George Soros – the billionaire philanthropist who is a frequent subject of many anti-Semitic conspiracies – as well as less likely liberal celebs, including Tom Hanks and Chrissy Tiegen. It’s easy to scoff at QAnon’s far-fetched ideas, (followers believe that the celebrity elite drink the blood of children to regenerate their lifeforce), yet reports on their growing followers make for sombre reading. This is no joke: the FBI has labelled QAnon a domestic terrorism threat; Reddit has a support page for those who’ve lost loved ones to the cultish grip of QAnon’s ranks.

When I was a kid I associated conspiracy theories with cartoonish American documentaries, the kind broadcast late at night on obscure cable channels. They were about the paranormal activity of the Bermuda Triangle, the supposedly faked footage of the moon landing, all the furtive secrets of Area 51. I’m sure even then there were many people embroiled in more dangerous conjecture, but there’s no denying that this last decade has been rocket fuel for increasingly violent conspiracies and fringe movements. The current climate is detestable – loved ones of victims killed in mass shootings are harassed online; the manosphere celebrates violence enacted on women; in August, 4Chan lit up in support of ‘vigilante’ Kyle Rittenhouse who shot two unarmed Black Lives Matter protestors dead. The internet has a lot to answer for.

We know by now that our online worlds are not uniform. The web is far from objective, what we see on social media is an amalgamation of who we follow and what our data suggests we like. Algorithms internalise the human biases of online users and their original developers. Even Google’s search results vary depending on location. The rise of fringe groups has been exacerbated not just by the globality of the web, but the increasingly tribal factions of the online world. We may like to think of ourselves as separate from the groupthink of the fringes, but if we’re honest with ourselves, how many of us truly expose ourselves to viewpoints we disagree with? How often do we use social media as a venue for open discussion? I can only speak for myself, and the answer is not often.

The problem with this is that for the aggressive and the disenfranchised, it becomes easy to channel toxic emotions into communities that say your anger is justified, that tell you you’re smart for seeing behind the veil. In these forums, confirmation bias rules – the ridiculous becomes viable. The reality of fringe, far-right groups is that though they may be sidelined from mainstream culture, in their totality they make up vast portions of the global population. Their recent flourishing has become symptomatic of a political system wracked by partisanship, oneupmanship and right-wing populism. In the instance of QAnon, the line between the fringe world of conspiracy theories and real, mainstream politics is already beginning to blur.

To date, two Republicans known to have expressed vocal support for QAnon have won Senate primaries: Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Witzke. President Trump himself has refused to debunk the theory. When asked in August about the conspiracy and his supposed role in waging war against the deep state, Trump’s insouciant response followed that he knew little about QAnon other than that they ‘like me very much, which I appreciate’. It’s a concerning (yet unsurprising) response from a man who has shown time and again that his supporters will always be met with praise, regardless of dubious ethics. In impact, it’s solidified the beliefs of QAnon’s already dedicated followers.

As we draw closer to the US election, Trump seems to be actively stoking suspicion. Viewed in isolation, his bizarre comments that Joe Biden is controlled by ‘people in the shadows’ seem like nothing more than typical Trump bluster, but in light of his knowledge of QAnon, it seems a darker tactic altogether. Experts are growing increasingly concerned about Trump’s posturing in the lead up to the November election; he has been characteristically blasé about his engagement in voter suppression, he continues to preemptively characterise the result as ‘a hoax’. In the background, QAnon propaganda is already rife with calls to arms should mail-in voting go in the Democrats’ favour. Unfortunately, a Trump win doesn’t guarantee placation, either; his reelection would only legitimise QAnon’s far-right, extremist views.

Any person even passingly curious about conspiracy theories will have noticed how they have become increasingly overlapped in recent years, grown from the same source like mould in a petri dish. The paedophile trope is commonplace by now, and Jeffery Epstein’s arrest was seen by many as confirmation of the tip of an untold iceberg. Stateside, QAnon poses huge risks, ideologically and literally – but conspiracy theories of this kind are not limited by borders. In the UK, QAnon has intersected with 5G conspiracy theories and covid-deniers. A ‘Save Our Children’ march held outside Buckingham Palace in August was one of many globally, with other locations spanning Australia, Canada and New Zealand (in London protestors were seen waving ‘Q’ placards).

We live in a society openly intolerant of extremism, yet somehow conspiracy theories seem missing from the public’s fear lexicon. There have been countless cases of violence enacted by men (predominantly young, white men) where proven links to far-right, fringe online forums have been written off in favour of ‘lone wolf’ headlines. Facebook played a huge part in the spread of QAnon: its algorithm threw up more and more content to those who joined related groups and pages. In typical style, Facebook’s eventual crackdown came much too late. These increasingly volatile, wide-spread conspiracy theorists must be taken seriously; those who break ranks should be offered venues for rehabilitation to help with the unlearning of poisonous doctrine. Crucially, we must find new ways to convincingly stamp out fake news – and force tech giants to slow, not further, the spread of dangerous misinformation. Conspiracy theories might be fantasy, but the risk they pose is all too real.

You might also like…

As Christmas in Wales is further restricted by a new lockdown based on the sort of evidence we always have to take on trust, Nigel Jarrett looks at a coronavirus conspiracy theory and the issue of free speech.

Caragh Medlicott is a Wales Arts Review senior editor.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.