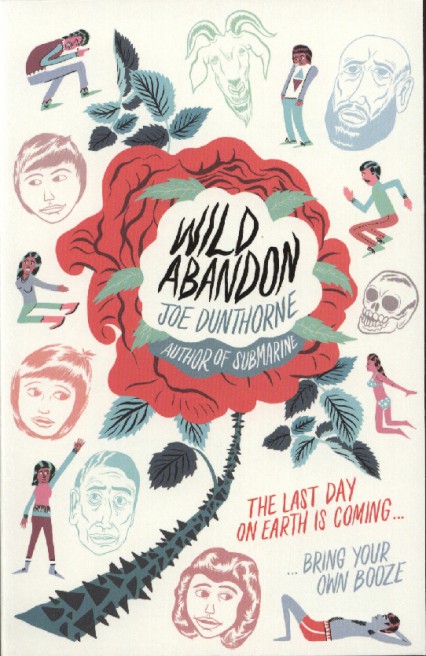

John Lavin casts a critical eye over the latest novel from Joe Dunthorne, Wild Abandon.

Following up a character as successfully realised as Oliver Tate – the hilarious, borderline-sociopathic hero of Joe Dunthorne’s debut novel, Submarine – might have seemed like a tall order; but in Wild Abandon, his sophomore piece, Dunthorne gives us not one but five major characters to relish.

The setting is a small commune in Gower. First and foremost are the siblings: seventeen year-old Kate and eleven year-old Albert, who instantly remind the reader familiar with Submarine of Dunthorne’s peerless facility for entering the adolescent mind. The memorable opening scene takes us from the community’s goat pen – ‘I’m going to milk the face off you,’ Albert told the goats. ‘I’m going to milk you to death’ – to the communal shower, which Kate and Albert share, partly because Albert refuses to wash otherwise, and partly because the community’s solar-powered water heater only has enough hot water for very short showers:

When the shower water ‘turned’ – channelling deep-chilled hill water – the screams of visiting back packers could be heard from the bottom of the garden.

The inappropriate nature of a young woman sharing a shower with a boy on the cusp of puberty provides a fitting introduction to the topsy-turvy world of the community (or ‘The Rave House’ as it is misleadingly known to locals.) Formed by Kate and Albert’s parents, Don and Freya, along with two other friends, the community has turned into a breeding ground of seething resentments far removed from the Utopian ideals which instigated it.

by Joe Dunthorne

pp.241, Penguin £8.99

Don, in particular, is a masterly creation: a sympathetic character and yet surely one of the most annoying in contemporary fiction. Much of the true comedy gold in Wild Abandon is inadvertently down to Don. In this instance, he is talking his son through the advantages of his ‘Human Filter’; a hat, glove and wire device he has created as kind of rites-of-passage for teenagers at the community (based on a genuine work of art by the Polish artist Wodiczko, called the ‘Personal Instrument’); while his longsuffering wife chops wood nearby:

The chopping sound slowed.

‘It’s an example of how we sometimes take for granted the way in which the world influences us….’ The chopping stopped. ‘…Think of all these inputs as ingredients in the recipe that will go to make you – Albert Riley – the delicious fluffy man-cake that we all hope you will rise to.’

The chopping started again, faster now. Don moved his hands around, opening and closing his palms as though practicing t’ai chi.

Freya, as we may gather from this extract, has reached the point whereby her husband’s self-righteous proselytising about the importance of ethical living and the community make it difficult for her to be in the same room as him. She feels that he is placing more importance on his ideals than on her own welfare and the welfare of their son, who is becoming increasingly dysfunctional. One example of the way he has consistently neglected her own feelings is the way in which he has fondly called her ‘the executioner’ ever since she dispatched the farm’s first pig. It is a name – and a job – that has stuck but it had been Don who had been meant to kill that first hog. However, ‘the night before the slaughter, while julienning spring onions, he took the lid off his trigger finger.’

Another character at odds with Don is Patrick, he and Freya’s ex-landlord and one of the founders of the community. Importantly, he is also the man who, until he suffers a bhang lassi-instigated broken ankle, has been the community’s main source of funds since its inception. Once in hospital he refuses to return to the community. Don is deeply upset but is so lacking in self-awareness that he fails to realise that the real root of his disquiet is the loss of Patrick’s money. Patrick himself, is far from in the dark regarding this matter and when Don, against his wishes, comes to visit him in hospital, hurls a bag of urine – ‘one and a half litres’ – at his former friend:

Don… thought for just a second that maybe it was some kind of welcome, a conciliatory balloon perhaps, and this expression – a golden balloon, for me? – was the one he had when it hit.

Patrick leaves the community for a flat in the Mumbles and Kate, unable to cope with her parent’s marriage disintegrating around her while she revises for A-levels, moves in with Geraint, her boyfriend, and his ultra-suburban parents. Having been brought up to believe that the outward normality of suburbia is merely a front for a deep moral malaise, she cannot help but distrust the kindness shown to her there. When she finally leaves she is convinced that she has been wrong about this. Unbeknownst to her, Geraint’s father has spent many years being blackmailed by a woman he once slept with while abusing his capacity as a bereavement councillor.

Wild Abandon is a novel of such ironies. Dunthorne is a marvellously non-judgemental author and yet, not a cold one either. He has affection for his all his characters, while at the same time not shirking when it comes to showing them in their best and worst light. Stylistically the novel is an interesting mixture of the old and the new. Dunthorne has as a rare grasp of how contemporary British society works – and what it sounds like – but the novel itself is structured in a way that recalls British ensemble-piece novels of the late 1950s and early 60s like Iris Murdoch’s The Bell (another novel about a community) and Kingsley Amis’ Take a Girl Like You. Like Amis senior, he has a great gift for comic timing – you have to wait approximately thirty pages before you find out what the frequently referred to ‘wwoofers’ stands for, when you finally do it is ‘worldwide opportunities on organic farms’ – but the novel is also steeped in a very human sadness: the sadness of the end of a marriage – and of love seeming to do more damage than good.