Over the next week, Wales Arts Review will republish pieces from our archive that we hope will contribute to the conversations going on in relation to #BlackLivesMatter. We hope to offer a Welsh context to some of the issues, and to encourage further conversations, reflections and, hopefully, change.

This piece was originally published in November 2019.

*

On the 180th anniversary of the Chartist Uprising in Newport, Shaheen Sutton asks, what has happened to the story of the black chartists?

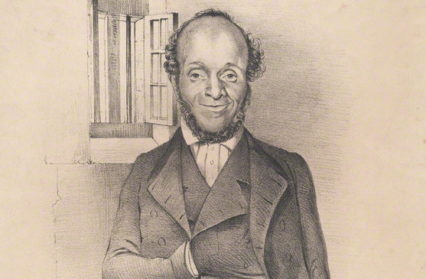

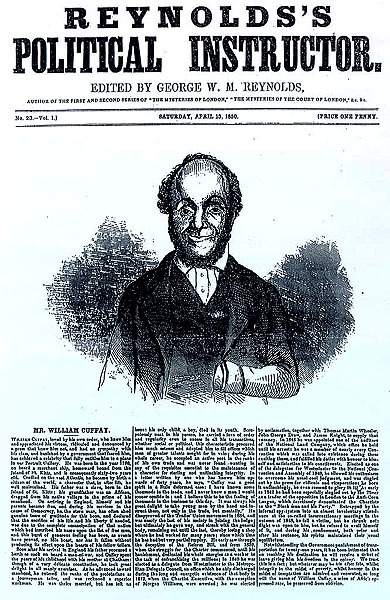

This year marks the 180th Anniversary of the Uprising in Newport, famously led by John Frost. This has been widely hailed as the first mass political movement of the British working classes, and a pivotal moment in Welsh history. As children in Britain are proudly taught, the Chartists’ aim was to achieve suffragette rights, inscribed in a People’s Charter. But not heroicized in schools, and all but now forgotten, yet every bit as worthy of recognition, was William Cuffay (1788-1870). Cuffay helped link Newport to the broader movement of Chartism in Britain, and emerged as a prominent leader of the organisation. He was dubbed ‘the Black man and his party’ in the national media. William Cuffay was the forgotten Black Chartist.

Cuffay was born in Chatham, in Kent, the son of a white English woman and a former slave from St Kitts. He was born with deformed spine and shin bones, and in adulthood was a physically small man, 4’11 tall. Neither his ethnicity or disability thwarted his determination to succeed. He became a successful London Tailor by profession.

Although always interested in working class politics, his awakening came when he joined the strike called by the Grand National Trades Union in 1834. For striking, he was sacked from a job he held for many years. It was not long after that he joined the Chartist movement. Cuffay made immediate impact. In his first year, he helped set up the Metropolitan Tailors Charter Association. After one particularly impassioned and effective speech, ‘on the Peoples Charter’, around 80 people joined.

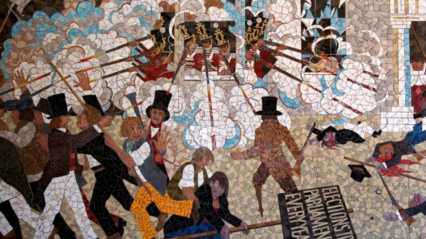

My introduction to William Cuffay and the Chartists was twofold. Growing up in Newport, I’d often walked past a wall in what was once John Frost Square (now Friars Walk), where there was a magnificent mosaic mural depicting scenes from the Newport Uprising. This mural was controversially demolished in 2013. In hope, I would scan the mural to see if there were any black and brown people amongst the Chartist marchers. As a kid already struggling with her sense of belonging and identity in Wales, I began to wonder about issues of representation and inclusion. Although Newport had the second oldest multicultural community in Wales, nonesuch were depicted in the mural.

Undeterred, this led me to want to learn more about the experiences of other black and minority people who came before me and made a home in Wales. In my late teens – as a nascent Socialist – by fortune I picked up the book Staying Power by Peter Fryer, and that is where I discovered that there had been at least one Black Chartist called William Cuffay. This man immediately tied me to a history that had previously excluded me: this was my British and Welsh history too.

On November 4th 1839, thousands marched down Stow Hill in Newport to the Westgate Hotel chanting their demands before a violent battle with police ensued. 22 Chartists perished and 21 were charged with high treason. Three prominent leaders, John Frost, William Jones and Zephaniah Williams, were arrested and subsequently sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered at The Shire Hall in Monmouth.

In a tangible link to these events, a month later at a meeting of the Metropolitan Tailors Association, Cuffay moved a motion in support of the Newport Uprising, raising the following resolution…

That it is the opinion of this meeting, that the insurrection in South Wales has been brought on by the injustice and cruelty of the government; first, by the insulting and scornful manner in which they rejected the great petition of the people from the Charter. Secondly, by the cruel, unjust, and vindictive treatment of those …, suffering incarceration in various dungeons throughout the kingdom; … We therefore do most deeply feel for, and sympathise with, our brethren in Wales, and with Mr. Frost in particular; and further, we pledge ourselves to use every exertion to save them.

Eventually, after a national petitioning campaign supported tirelessly by Cuffay, the government relented and decided that the three Newport Chartist leaders would be sentenced to transportation to Australia for life. In total, sixty Chartists were transported from Monmouthshire to Van Damiens land in 1842.

By the mid 1840s, now in his fifties, Cuffay was gaining growing recognition as the Black Leader of London Chartism. The more prominent and influential his powerful and eloquent orations, the more he was targeted by opponents in the press. Inevitably, Cuffay’s skin colour became a focus for ridicule. Indicative of his growing importance, Cuffay was even racially caricatured as a savage by the otherwise more reformist satirical forerunner to ‘Have I Got News For You,’ Punch magazine.

The last significant Chartist demonstration was at Kennington Common in 1848. Here, William Cuffay was arrested for conspiring to levy war against the Queen. Tried at the Old Bailey, he remained a dignified figure throughout the trial, objecting only to what he saw as an overly middle-class jury, and to the nature of the evidence against him (which had been gathered by the police spies). Although he had many times spoken on behalf of others, his locality never sent any delegates to Cuffay’s trial. Left alone, he was sentenced to transportation at the age of 60 to Australia, for life.

The last significant Chartist demonstration was at Kennington Common in 1848. Here, William Cuffay was arrested for conspiring to levy war against the Queen. Tried at the Old Bailey, he remained a dignified figure throughout the trial, objecting only to what he saw as an overly middle-class jury, and to the nature of the evidence against him (which had been gathered by the police spies). Although he had many times spoken on behalf of others, his locality never sent any delegates to Cuffay’s trial. Left alone, he was sentenced to transportation at the age of 60 to Australia, for life.

This was not the first time I had come across a free Black man in Britain being transported to Australia. Black ‘criminals’ had been amongst the earliest transportees from late eighteenth century London. To paraphrase James Walvin, these were early globetrotters of the most unfortunate kind: from Africa to the Americas; from the Caribbean to Britain; and then in chains to Australia. The ironic thing about Black transportation to Australia was that in the 1830s the maritime slave trade had been abolished in the UK, but Transportation was slavery under different name.

William Cuffay’s prison ship landed in Tasmania in November 1849. Ever resourceful, he found opportunities to practice his trade as a tailor and eventually settled in Hobart. He received a pardon in 1856, but continued to campaign for the rights of working people. In October 1869, now in his eighties, Cuffay fell into poverty and became very ill and was admitted to the workhouse where he died, in July 1870.

Whilst eminently worthy of rescue from historic obscurity, William Cuffay was not the only Black Chartist. There were others, like David Anthony Duffy and Benjamin Prophitt, who both led demonstrations in Camberwell in 1848. There was William Davidson and Robert Wedderburn, both men the children of black enslaved mothers.

Nowadays, on the Anniversary of the Newport Uprising, we will rightfully recognise the sacrifices of the Chartists and the leaders. But we are not encouraged to think of the role of ‘the others’, the Black Chartists. In Newport, every year now you will see children from local schools enacting the protest Chartist March down Stow Hill dotted with black and brown faces, so is it far-fetched that in 1839 that there would have been Welsh black and brown chartists amongst them? I think not. I suspect the now removed Chartist mural already knew a thing or two about removing history.

It would not have been a significant number, but I have always continued to wonder how many of the thousands that marched down Stow Hill in Newport on the 4th November 1839 were – or were the offspring of – settled runaway slaves or freed slaves, ex-slaves co-opted to stand up and fight for their rights alongside working class white men; and how many of those that were buried in unmarked graves may have been black men, unnamed and unclaimed?

Knowing what I know now about Black people’s presence in Britain since Roman times, I cannot fathom that there were no black people at this protest. Whitewashing of aspects of British and Welsh history is not uncommon. My mind goes, for example, to Nathaniel Wells, whose social advance in Georgian Monmouthshire is another lost Welsh black story.

There is so much unearthing to do, in the same way the 1919 race riots in Newport have come to the surface on its 100th anniversary this year, other Welsh Black stories await telling. It is why it is important British Black and Asian History is be on the curriculum. Black and Asian History is British and Welsh History. William Cuffay is part of my history. And your history. A Chartist, a working-class hero. Where are the black Chartists? They are there, if you care to look for them.

Shaheen Sutton has worked in the changing field of equality, diversity and social justice, both in Wales and Scotland.