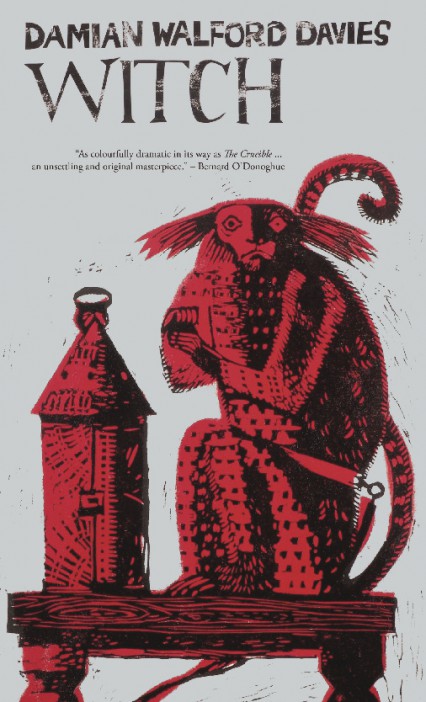

Laura Wainwright reviews Damian Walford-Davies latest collection, Witch.

‘My garden borders on the deadfold / where they murder down the lambs’, Thomas Love, a priest living in an English village in the mid-seventeenth century, ruefully confides in the opening section of Damian Walford-Davies’s brooding book-length poetic sequence, Witch. In this fascinating and deeply unsettling work, Walford-Davies vividly recreates the world of the Suffolk witch hunts, where scores of women and men were persecuted and brutally punished for allegedly practicing witchcraft. The largest witch trial in English history – an event that culminated in the execution by hanging of eighteen people – took place in the Suffolk village of Bury St Edmonds in 1645.

Set two years prior to this, from February 1643 through to March 1644, in the midst of the English Civil War, Witch records the events and exposes the social climate of hypocrisy and suspicion, and zealotry and corruption, that feeds malicious rumours about a mother and daughter and leads to their indictment as witches.

by Damian Walford-Davies

80pp, Seren, £8.99

Its seven parts, in which the characters at the centre of the hysteria all put forward their conflicting, subjective and often skewed accounts – from gossiping, superstitious villagers to the Witchfinder General-like Francis Hurst, ‘Discoverer of witches’, and Valentine Lind, the ‘Judge of Assize’ – lend the book an irresistible narrative drive. ‘She came / towards me on the causeway’, Nicolas Strelley, an influential local gentleman, claims, for example:

flaunting spears of loosestrife

from the marsh. My horse

shucked, stammered – pitched

me into rippling weed.

From the brink she offered

flowers. Sodden, I saw

my wife again, a woman

on a slender lip of land

drawn shrill against the sky.

Her purple petals dazzled. Love!

I tendered. Then I said it: witch.

Walford-Davies maintains the taut couplet form of the above lines throughout, eloquently reinforcing the poems’ interrelated themes of fear, obduracy and control. In its exploration of these themes and, of course, in its historical subject matter, Witch cannot escape comparison with Arthur Miller’s dramatic portrayal of the more famous 1692 witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts. Just as The Crucible spoke to the realities of McCarthyism in 1950s America, however, Witch has a similarly ‘shrill’ parabolic quality, warning against ongoing intolerance, discrimination and abuses of power in our twenty-first century world.