Steph Power spoke with Emma Jenkins, the associate director of WNO’s production of In Parenthesis, about this particular opera.

In David Jones’s World War I epic poem, In Parenthesis, legend and history, memory and reality collide in the cataclysmic Battle of the Somme. Jones was one of the few riflemen of the wholly outnumbered 15th Royal Welch Fusiliers to survive their fateful engagement with the Germans at Mametz Wood in July 1916. The work he wrote some twelve years later about his experiences up to and including that infamous event defies classification. Part reportage, part eulogy, part autobiography and part collective dream, it stands as one of the great landmarks of 20th century literature and as testament to a time in which cherished illusions about the nature of modern civilisation were stripped away forever.

Adapting In Parenthesis for the operatic stage demands particular skill and sensitivity. When David Antrobus and Emma Jenkins called on Welsh National Opera to answer that challenge, the company responded with a commission for a new opera from composer Iain Bell, setting their jointly-written libretto. The work commemorates the centenary of the Battle of the Somme in celebration of the company’s own 70th anniversary this year.

Directed by WNO artistic director David Pountney and conducted by WNO conductor laureate Carlo Rizzi, the world premiere of In Parenthesis takes place this Friday, May 13 at Cardiff’s Wales Millennium Centre. During rehearsals, Steph Power talked to Emma Jenkins – also the opera’s associate director – about Jones’s poetic intent, and his unique imagery, narrative style and use of archetypes within a rich tapestry of allusions. Together they explore how Jones envisioned all wars past and present through the prism of the Great War; and how she and David Antrobus seek through their libretto to honour that spirit and the ‘many men so beautiful’ who fought at Mametz.

Steph Power: It’s Welsh National Opera’s 70th anniversary, and the company has commissioned a major new opera, In Parenthesis, to commemorate the centenary of the Battle of the Somme. That’s a very significant act of remembrance.

Emma Jenkins: Yes it is, very much so.

Steph Power: How far is David Jones’s poem itself an act of remembrance?

Emma Jenkins: It is an act of remembrance, but not in the sense of other war poets. I think it’s completely unique in the canon; I don’t know if you can even say that this is a ‘war poem’ in the conventional sense of that phrase.

Steph Power: What was Jones seeking to do in your view, and what makes his poem unique?

Emma Jenkins: This is very much an artist looking back through the prism of memory; it was ten years after the war before he even started work on In Parenthesis, and it wasn’t published until 1937. It’s about how events become twisted, changed, even fantasised over through memory and time. You can’t really say that David Jones is a poet or an artist or an engraver in a conventional sense – he called himself a maker of things, always looking for the right form to express what was in his mind. In his art he looks through ordinary events and objects and sees something extraordinary and fantastical beyond. I think his catholicism is important here because of the idea of transubstantiation; the idea that with that cup you’re holding, I don’t just see the cup, I see the grail. It’s about the idea that we’re all connected by a cultural ancestry.

These ideas pervade In Parenthesis. I guess it’s something that could really only happen in a pagan English or Celtic context, where you see the essence of magic inside something ordinary. Of course there is the basic story of the journey of these men to Southampton and to the frontline, then finally to the Somme where they meet their deaths. And that’s all very important. But Jones is immediately penetrating that veil and seeing through it to, for example, the story of Y Goddodin. He’s seeing these men who are also warriors from the 6th century perhaps, or soldiers at Cresson. He sees a soldier giving out rations in the trenches as communion.

Jones never sees something as it actually is. But he does more than that. He brings all that history and legend into the present moment ‘as if it happened on that very spot right here, right now’ as he says at the beginning of In Parenthesis. So we’re not just looking back and saying oh, wasn’t it dreadful. We’re looking back and seeing all wars, all warriors that have ever been, coalescing in a single moment. And we’re bringing them forward into the present, living it as if it was happening right now.

Steph Power: So as the veils are pierced we enter a kind of timeless zone?

Emma Jenkins: Yes – where these soldiers can link minds with their ancestors. Jones sees a man climbing Queen’s Nullah which is just before Mametz Wood; they’re all caked in chalk with their tin hats on – they could be from The Vision of Piers Ploughman, or from Agincourt, with exactly the same tin hats.

Steph Power: Why do you think Jones chose to write about this eight-month period up to Mametz? He fought at Ypres and Passchendaele too.

Emma Jenkins: It’s very significant. I think it’s because we’re at a turning point in how war is waged. This is the very last time we could look at soldiers and say this is how war’s always been fought. After 1916 there’s a more mechanised form of warfare; what we would recognise as modern warfare, with what Jones calls ‘tractored howitzers’, modern artillery and ammunition. After that period, you probably couldn’t make these connections, pierce the veil in the same way, look back and see something magical and timeless – something legendary, actually.

Steph Power: In Parenthesis seems to capture a turning point in the whole idea of modernity; part of that is how the new technology sits alongside references to Malory, say, and ancient Welsh poems. Jones talks a lot about the new inventions of the chemists, the poison gas. I suppose it’s the first use of weapons of mass destruction – and then the awfulness of the slaughter at Mametz with the machine guns. That too marked a sort of turning point in how humanity viewed itself.

Emma Jenkins: Yes. I think so, very much. And don’t forget they didn’t even get things like tin hats until February-March of ’16; that’s the first time they even get issued with the proper covering rather than soft hats! People think WWI uniform is a specific thing, but it’s not, it was very make-shift. Everyone looked a little bit different: some wore sheepskins, which would have been literally bits of old fleece with holes in, tied around. Nothing is the same after this period and I think that really interests Jones.

A toxic form of warfare came in. He talks about that quite specifically in Part 3 where there’s this destruction of the mangold field. As always with Jones it’s the mangolds’ bleeding their bowels onto the field, as it were, that captures his imagination. He’s got that almost autistic attention to detail, obsessive focus on a single thing. Very like an artist – actually the whole poem is very like an artist’s storyboard.

Steph Power: The imagery is strikingly visual isn’t it? Of course he was an artist and had studied at the Camberwell and Westminster schools – the opera is subtitled ‘an Artist’s Vision of the Somme’. I think his father was a printmaker too?

Emma Jenkins: Yes, in Rotherhithe. So Jones is a sort of cockney, really – a Welsh cockney. [His father was Welsh and his mother, English].

Steph Power: Like many of his fellow Royal Welch Fusiliers at that point.

Emma Jenkins: Yes, they were cockneys with a mixture of Welshmen. That’s actually important too.

Steph Power: What did that mean for Jones’s use of language, and of slang?

Emma Jenkins: He describes two racial groups that at first you wouldn’t think to be so similar, but they each talk in parables; they each have their folklore and their musicality of language and slang, and they share a common military slang. I can’t remember the exact quote, but in the preface to In Parenthesis he says: ‘These came from Wales, those from London. Together they bore in their bodies the genuine tradition of the Island of Britain.’ So we’ve tried to bring that out in the opera. We have our cheeky chappies Watkin and Wastebottom; a cockney and a Welshman who have a special relationship. Then there’s Lewis and Ball. Again, Lewis is the Welshman, steeped in his Welshness. He can trace his ancestry back beyond Llewelyn – even to Aeneus, before Britain was Britain. And then you have the cockney, Ball, who rather wishes he was a Welshman.

Steph Power: Like Jones himself: Private Ball is Private Jones, in effect.

Emma Jenkins: Exactly. And Jones is obviously very into his Celtic heritage but he’s a Londoner, Anglo-Welsh. It was very important for him to join a Welsh regiment. He’d heard Lloyd-George speak of raising a Welsh army of the sort that had fought in bygone times, and he took it very seriously. He wanted to be a soldier. He was totally incompetent – like Ball – but he wanted to be a proper soldier.

Steph Power: When Owen Sheers was researching his play Mametz, he was struck by the patriotic, almost blood fervour there was to join up. My sense is that Jones felt it as a kind of historical need to defend the Celtic races, and that’s part of what gets fed into the poem through the many ancient and mythic tales to which he alludes. To me the bardic references feel key here. In the opera, you’ve introduced the Bard of Germania and the Bard of Britannia, a soprano and baritone respectively. Can you say what they are about?

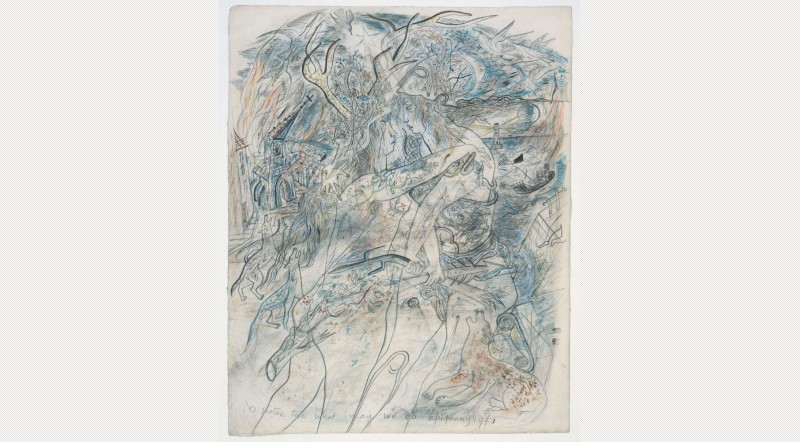

Emma Jenkins: We were really inspired by Jones’s later WWII painting, Epiphany 1941: Germania and Brittania Embracing. We wanted to have a narrator or narrative force; like a Greek chorus in a way, so they would drive the narration but also participate in it. So we thought let’s create two Bards, one called Germania and the other Brittania! And they’re big roles – they’re really important. They’re virtually never off stage; in fact, no-one is ever really off stage, it’s a marathon, especially for Ball [who is sung by tenor, Andrew Bidlack]! But these roles are very important.

Obviously this is about the WNO chorus as well, and we wanted to create something special for the ladies. There are no women in In Parenthesis, so we wanted to create a female force, a Chorus of Remembrance, a Chorus of Dryads. That force is like the force of nature, they are the spirits of Mametz Wood. I suppose you could call them the receptacle of memory. They are the ones who say we must remember, and who bring that up to the present day. The Bards dictate how the Chorus of Remembrance drives the opera, and how it occasionally interacts with the characters – and how the Chorus then finally transforms the tragedy into something transcendent and beautiful.

Steph Power: Right. So those roles are the dramatic pivot as it were, of that simultaneous past and present which affects Ball and the other soldiers?

Emma Jenkins: Absolutely. Think of it as two parallel universes, running alongside. In one universe you’ve got the temporal world, soldiers and life in the trenches. Alongside it is this parallel universe of myth and legend, of amazing things where unicorns can suddenly appear in the wood. That world is the world of the Bards and of the Chorus of Remembrance. Initially it’s the temporal world that predominates. But because Ball the visionary has a foot in both camps, he’s always seeing into the other world and being influenced by it. And finally that world becomes more and more prominent. Really, by the end of the opera it subsumes the temporal world so that these soldiers have completely become one with their ancestor warriors of the past. They’ve become legends in their own right.

That then allows us to have this resurrection at the end, where the Queen of the Woods changes her form into the benevolent giver of life. She garlands the men and each of them receive a special flower that allows them to then be reborn in nature with the promise that they will live with her for a thousand years. It is a dreadful tragedy of course. But I think the way Iain’s written it, the audience will come away feeling really uplifted. It’s not what you expect at the end of all of that – he’s done an amazing job, just fantastic, sounds I’ve never heard before. There’s a fifteen-minute period where everybody dies in this ghastly carnage, and then suddenly the Queen of the Wood appears and the wood becomes regenerated and the men are reborn. But for Ball, the punishment, if you like, for being the survivor is that he has to keep telling the tale again and again and again like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and the wedding guest. It’s that kind of relationship.

Steph Power: So there’s a kind of Orphic reading of the underworld journey there – and the Ancient Mariner is another very clear theme of In Parenthesis isn’t it?

Emma Jenkins: Yes, it’s really important, that idea of a survivor, and the survivor’s guilt and the job of the survivor to tell the tale; to bear witness and to remember and to make others remember. That’s why Jones grabs the reader and demands their attention. That’s what the Bards are doing at the start of the opera to us the audience. They’re saying listen to our tale. It’s their way of purging themselves. At the end it’s Ball, the only survivor of this event, who has to take on that mantle; to be the Bard, and the one who has to sing that song in perpetuity.

Steph Power: One of the debates around In Parenthesis has been how difficult it is to talk about the awfulness of war and the bravery of soldiers without somehow ennobling war itself. What are your thoughts on that?

Emma Jenkins: Jones actually had a bit of a bee in his bonnet about that. Paul Hills, the art historian who knew Jones, tells a lovely story. Somebody criticised Jones for trying to make the tale heroic and he threw a book across the room and he said words to the effect that, ‘compared to running around the corridors of Westminster Arts School what we did was bloody heroic!’ We weren’t there, this is a man who was. If that’s how he saw it, who are we to judge or bring our political correctness to it? It’s a thing we could never understand. This is a man who never really recovered from what we would probably now call post-traumatic stress disorder.

He doesn’t glamorise war – quite the opposite! He’s just saying war happens, it’s always happened, it will always happen, and in these intense, heightened moments of existence somehow we open ourselves up to experiences we might never have in another situation. And you know, he’s not talking figuratively when he talks about being invested with the spirits of warriors past; with Llewelyn literally coming into your body and taking over you, or Henry V or any of these characters – or Maximus even. He means it literally, as a visceral experience. It’s as important as daily life in the trenches, like being out on fatigues; it’s as real to him, and it’s as real to war.

Steph Power: There seems something fundamental here about the nature of trauma, that relates not just to war situations but to anybody who’s experienced what that does to perception. And perhaps people sometimes confuse the nobility of Jones’s writing with an ennobling of war. He’s writing about a situation that is completely mad. But is he attempting to create meaning out of it in any usual sense?

Emma Jenkins: It is insane. But more than making meaning, I think he’d probably say he was trying to make a shape for it. He’s never really about meaning in an intellectual or academic sense, for him it’s all about a shape. I think In Parenthesis is like a spatial reasoning puzzle. Writing the libretto was a bit like that – it’s not like saying, well, we’ll take this theme, we’ll take that theme and just bang it all together! I really think Jones was trying to find his place in the whole thing, and its place in the whole canon of myth and legend and to find a shape for all of that. He’s a very objective writer actually. It’s almost like a camera, or a reporter’s eye view, given without necessarily stating a subjective opinion. And because he’s got that artist’s eye, it comes out as this sort of storyboard. It’s very modernist.

This is written through the prism of memory, and how memory changes everything – you augment certain things, don’t you, and you forget other things. So there are lots of points that are inaccurate historically, if you look at the actual regimental diary. It was never meant to be an historically accurate account.

Power: Jones actually says in his notes on the poem where he may have remembered something wrong. It’s almost as if he’s still talking to himself or to his memories when he writes those notes. It’s unimaginable what he must have been carrying having lived through the Somme.

Jenkins: He never got over it. It was with him every single day and he became increasingly agoraphobic as he got older. He’s very open about it and says that once you’ve been knitted into the texture of the trenches, you’ve become assimilated and you’ll never be the same again. You’ve become part of this place out of time. And that’s how he lived his life from then on.

Power: You mentioned Jones’s catholicsm earlier. He converted in 1921, before he started writing In Parenthesis – and he went to live with Eric Gill and his family in Capel-y-Ffin.

Jenkins: Yes he lived with Eric Gill and was engaged to his daughter Petra for a while. His sexual repression is quite well documented – it’s important because it makes him the artist he is, and I think you can see that. His relationships with his fellow soldiers were very important but again it’s very difficult to say where he was coming from with all that. But the way he views women is very interesting: as something on a pedestal, something removed from him. I suppose it helps us understand how he can make that link to the idea of the destroyer and the creator; the Queen of the Woods as this sort of benevolent giver. And also the way he paints women is very iconic.

Power: How does it feel to be making an opera of In Parenthesis in Wales, where it’s such a revered text – and for good reason?!

Jenkins: That feels alright! Well, it was our idea in the first place; we proposed it to David Pountney, though I don’t think either of us thought it would escalate like it has! There’s quite a lot of hype around it now, which we’re just ignoring. We can just do our best – nothing is more important than representing this poem in a way that will honour David Jones and the men at Mametz. And everything so far has either come up to our hopes or exceeded them. The music is beyond what either David or I could ever have dreamt of. Iain just dived into that idiom straight away and he writes from the heart, so that’s fantastic. David Pountney’s vision of the production couldn’t be more sensitive – it’s just wonderful the way he’s conceived it. And we’ve got a dream cast who, again, are so able to grasp the idiom.

It’s not easy but I think there’s been so much preparation for everybody in terms of dramaturgy ahead of time. Iain’s prepared them all so well; six, nine months before they’ve even come to rehearsal. So I don’t think we could have done anything more – we’ve done our very best to make this a sensitive, hopefully very beautiful and inspiring, uplifting experience. It’s a tragedy but people should go away feeling good, just as David Jones did when he saw the pictures of Mametz regenerated; he didn’t go back there himself but friends did, and he was bowled over by how nature could take the wood back and return it to its sappy, almost pagan, regenerative greenery.

Power: The opera has two acts: the title of Act I, ‘The Many Men so Beautiful’, comes from Jones’s first part, and the title of Act II, ‘The Five Unmistakeable Marks’, from his seventh and final part. So the interval between them takes on board the six-month gap in Jones’s poem.

Jenkins: Yes. We did consider keeping seven parts, but you can’t – not in a piece of drama.

Power: No, of course not. What feels key is that you’ve put the Boast of Dai Greatcoat at the end of Act I, with the Queen of the Woods echoing him in a way at the end of the piece. Dai seems to embody the bard as man – he can’t physically see the fantastical characters in the way that Ball can. Nonetheless he himself channels the idea of the otherworldly bard – through the spirit of Aneurin in Y Gododdin, for example.

Jenkins: That’s right, Dai does very much channel that spirit. He’s this ancient soldier – no-one knows how old. And that’s part of the humour in the Boast of Dai Greatcoat: you know, ‘I’m older than you, I served with the Black Prince’ – ‘well, I served with Lucifer’ – ‘well I was there at Calvary’! Dai is this legend of a man and soldier. Who nows how long he’s been at war? – he’s never been out of it. And yes, the spirit of Aneurin, the spirit of Llewelyn – ‘before and before and before again’, as David Jones says – are all within him.

He’s deeply into his Welshness and he’s very special to the Queen of the Woods because he is that pagan man who’s walked with Merlin, and so she says at the end, ‘I have a very special one [flower] for Dai’. Dai’s death is hopefully incredibly poignant – though of course each death is deeply moving, and the guys are doing an amazing job! When we were writing I felt the part of Dai had to be Donald Maxwell – so it’s wonderful that he’s free, and he couldn’t be more pleased. But when Dai gets hit, there are these incredible horns that swell, and he doesn’t sing that much as he dies, just ‘Mam, mammy, mother of me’. And then it’s as if he seizes the Golden Bough, demands the fructification of the land. It’s just very beautiful the way he dies – if that’s possible!

We really wanted to bring Dai centre stage because the legend of Dai Greatcoat is the soldier Jones always wanted to be. This is a man who’s survived every single war since Calvary, perhaps since Lucifer’s rebellion, but he dies here on these fields.

Power: Jones’s language is very Shakespearean in places, alongside all the slang – with references to Henry V, Macbeth and so on – just as we honour 400 years since the death of that particular bard! Actually I often think of Birnam Wood in relation to the wood at Mametz.

Jenkins: Yes, I do too! And in Part 4 when he’s looking out and sees Biez Wood and we have that famous passage ‘To groves always men come both to their joys and their undoing’. And you’re bound to think of Henry V, that’s so important to Jones, he memorised big chunks of the play. It’s on these same fields.

Power: This entire four years of WWI commemoration is a chance to re-evaluate the 20th century and where we are now. Everything we’ve touched on seems testament to how the poem – and from what you’re saying, the opera – encapsulates reflection on an epoch rather than a simple act of remembrance.

Jenkins: Yes, I do hope it comes across as something much deeper. This should hopefully feel a little bit different, and a bit fresh and unexpected too.

Power: It feels important that, through the Bard of Germania, you’ve named the Germans – given their national-mythic element a voice if you like. And through that the German soldiers, who would have been going through the same things in the trenches.

Jenkins: Yes, Jones doesn’t make this a Welsh tragedy. This is something for everybody. At the beginning of In Parenthesis he says for ‘the enemy front-fighters who shared our pains against whom we found ourselves by misadventure.’ He makes no distinction, there is no partisan sentiment. Someone I spoke to recently was quite keen to say this is a Welsh tragedy. But it just isn’t! This is about men. That’s it. Of course it’s a big Welsh tragedy, but Jones is not writing from that point of view. He honours ‘the bearded infantry who we shared our long loaves with’.

He’s not interested in Wales, England, Scotland in a nationalist sense. He’s interested in the Isle of Britain, that ancient isle right back to Maximus AD 383 and further, when we became part of the Roman empire. If he’d known about genetics he’d probably have been interested in the fact that we can all trace our genes back to a single eukaryotic cell in the primeval soup – that shared pool of ancestral memory. This is why the character of Lewis is very important – because Lewis can trace his ancestry first back to Llewelyn, then back to Romulus and Remus and beyond, to Aeneas. Jones says ‘the towers of Troy still burn’ for Lewis, who lives that reality. He is the son of Aeneas, not ‘just’ a Welshman. It’s a kind of cultural connectivity that we’ve probably lost as a society, whereas Jones still remembers that time when, if you put your cup on the table, all of us would think of the grail, not just one of us. We’d have a shared moment where we would all penetrate that veil.

Power: In the poem the whole area of battle – not just that area between the two frontlines – feels like a no-man’s land. Maybe that’s part of Jones’s title, In Parenthesis; indicating a type of space as well as being somehow out of time. But the area’s more than that – it’s paradoxically also a kind of everyman’s land.

Jenkins: Yes absolutely. And if you think of the gap between the frontlines it could sometimes be only a matter of a few metres so they could hear each other coughing and moving around. That’s why when they went on these night sorties they would sometimes jump into the wrong trench – they thought they were at their own. We’re talking feet in places, it’s crazy. That whole idea of the ‘stand to’ as well – this moment where they all stood at dawn and dusk. They would have seen the whites of each others’ eyes. I find that unbelievable.

Power: You’ve popped a Christmas truce into the opera, where the two sides come together for a brief moment in no-man’s land.

Jenkins: Well we’ve sort of cheekily popped that in. It’s not the famous Christmas truce but we really wanted to make something of that. We wanted to hear the Germans and we thought it would be lovely if they sang ‘Es ist ein Ros’ and then the Fusiliers sang back. In the original poem they sing ‘Casey Jones is Mounted on his Tractor’ – or something like that! Which is an old cockney song and wouldn’t really have worked in the opera, so here it’s a carol. In fact the German officer is out in the auditorium, so in a sense the orchestra pit is no-man’s land. We’ll hear that sound coming across the audience and then everyone comes forward onto the forestage and sings back.

Power: That sounds very powerful!

Jenkins: I hope so. There should be lots of unusual moments like that, that would be unexpected in more usual interpretations of WWI events, or productions that honour it.

Power: It’s an extraordinary text. To honour In Parenthesis you can’t do anything conventional – and Jones wasn’t that himself.

Jenkins: No. We’ve gone all out really to bring out that essence in the production as well. We’re not holding back.

Header image courtesy of WNO. For further information about Iain Bell’s In Parenthesis, go to WNO’s dedicated mini-website: http://inparenthesis.org.uk/

All rehearsal photos, credit Betina Skovbro