Helen Calcutt experiences Owen Sheers at the Alan Garner Centre in Wolverhampton where he discusses his work such as his poems, Pink Mist and World Maps.

The translation of pain into language gives remarkable energy to any piece of writing. Literature that draws from the suffering of another, or of oneself, is crucially honest, and while most writings are ‘not equipped for life in a world where people actually die’, some master the articulation. The brutal honesty of this kind of writing (I can think of Janos Pilinszky’s Fable, Homer’s Odyssey, Poe’s Conqueror Worm) sustain the inevitable erosion that time’s passing impedes, and in their learned immortality, inherit a bleaker strength that somehow outlasts – and furthermore defines – what we (should) consider to be ‘long-standing literature’.

This idea – that things must make their mark – seems to have deeply embedded itself within the anatomy of Owen Sheers’ work. It occurs again and again, whether in writings of contemporary war, the beauty of the Welsh landscape, or ‘the victory of the human spirit’. This is a good sign – both the writer and his work are developing in synchrony. And the integral subject of the writing (that infinitely gentle, infinitely suffering thing) seems to be revealing itself.

Sitting in the small, perfectly heated library centre in Wolverhampton, I’m struck by the notion of ‘subject’ – that quietly centred seed from which most ideas or inspirations trickle. And it’s not that I’ve arrived with this already in mind. It’s the man himself who brings it to the table:

‘It’s a beautiful thing,’ he says, ‘people coming together to read and share poetry.’ He then goes on to explain that poetry (or good poetry at least) inherits a deeply profound sense of longevity which can be seen in World Maps. That once loved and learned embeds itself in the brain, like a watermark. Poetry; or any kind of heightened language; should be distilled ‘in the touch of wind’, or ‘the taste of rain’. There’s no denying Sheers’ almost benumbed dedication to producing this sort of work, and this desire to shape the perfect poem has perhaps originated from the ingrained belief that language has a distinct purpose.

There’s a call to this idea in his poem World Maps, with its ‘goose-bump patterns, black on brown/a disease of the skin, the legacy/of drinking Kava…’– but I find it explored more expansively in his dramatic verse for radio, Pink Mist.

Owen Sheers’ poetry is good, but his dramatic verse is excellent, especially in World Maps. His use of lyrical language in a dramatic context is both lurid and gentle – both human and quiet. His writing has always been ‘dramatic’, and the grafted weight of his poetry, in particular, demands aural attention. All this comes to a head in Pink Mist. He reads three extracts, all of them tailored to embroider those elements that make language so keen and purposeful. I’m not impressed by the actual presentation. There’s a slight effect to his voice that is suggestive of performance poetry that doesn’t suit. The dramatic verse is naturally taut; energetic. Those natural pulses and inflexions don’t need emphasising.

But I’m not detracted from the maturity of the writing. The whole idea of Pink Mist – the continuation of pain and suffering outside of battle, again, calls to the notion of ever-fixed marks. I get the feeling that, for Sheers, pain is incredibly important, and therefore must be articulated. Perhaps this is why war is such an enticing subject for him. His love of the works of poets such as Keith Douglas, Wilfred Owen, and Ted Hughes are suggestive of a fascination with the things that affect us: or rather shape us, in either a deeply profound and/or negative way. This could be a war of the battlefield, the landscape, or of the heart. For Sheers I think this is synonymous, though perhaps more prevalent in the emotional and physical journey of a soldier.

On hearing these first three extracts I notice a reference to earlier work. In one section he describes a bird egg resting among feathers. The image is incredibly precise, and incredibly concentrated, drawn-out quietly from the page, but beautiful nevertheless. I’m reminded of an earlier poem called ‘When you died’. In it, the lines read:

I, afraid of the sudden peck

Stretched my hand into the dark

To take the warms eggs, one of them

Wearing a feather

There’s a living strength to this image. And it’s echoed again in Pink Mist. Eggshells both protect and injured: they can be easily broken, and in breaking come to represent something different. There’s a soft, archaic afterglow in the presence of something collapsed, and I’m immediately reminded of The Hanged Man by Leonard Baskin. There’s nothing content about our internal (or external) scars, but like the image, every twine and ligament is focused at the surface, directing our attention ‘straight to its depths.’ It would seem that they exist for some purpose, perhaps to be examined, and in this painful revelation, healed.

In lifting the surface of these scars and articulating their depths, Sheers pencils his own mark of excellence. The same maturity and style grace the pages of Calon, a journey to the heart of Welsh Rugby, and Skirrid Hill, his second poetry collection. He reads from both, but neither compares. Sheers’ strengths have come to the fore in Pink Mist. Here we have the balance of heightened reality and hardened truth, coupled with human and spiritual intensity. There’s a new musicality to his writing that I love, and I’m particularly delighted to sense a strong feminine presence. Three of the characters in Pink Mist are women, and not only do we hear the stories of those left behind in war but also the prophetic, perhaps even somatic energy of the female voice. There’s a calling to this again, in earlier works. In poems from Skirrid Hill for example there’s some use of feminine rhyme, with the stress on the penultimate syllable of each line: and his relationship with women (mother, friends, lovers,) is frequently explored. But this presence doesn’t seem to be fully realised; perhaps at times even suppressed. In Pink Mist the female ‘other’ is dutifully embraced – she is allowed to speak in full volume – and again, Sheers proves himself as a writer of both depth and maturity, whose work forever strengthens, offering a richer experience for both the reader and listener.

In the Q and A Owen Sheers was asked how he was found returning to the format of straight poetry. The answer was ‘difficult.’ I’m not surprised. I think perhaps this desire, or need to write in a dramatic context has always been evident. If we look at Skirrid Hill, we open with the poem ‘Last Act’- a dramatic opening to a lyrical sequence. We have ‘Intermission’, a poem that provides balance, and lastly ‘Skirrid Fawr’ a wholesome albeit elegiac end to an intimate journey. And still, there’s this idea of marks. In poems such as ‘Shadow Man’: ‘it isn’t the number of steps/that will matter/but the depth of their impression’, ‘Mametz Wood’, ‘Marking Time’, ‘Swallows’, ‘Keyways’, ‘Hedge School’, ‘Landmarks’ and ‘Skirrid Fawr’ – this recurring image bleeds from almost every page until eventually, it is there itself like a wound. Clear and unimagined.

How satisfying to know of an artist so fully engaged with the internal workings of his own creativity, and at the cusp of, what might be, the total realisation of subject. But there’s a final struggle to be had – or perhaps a final question to be asked. I wonder – has Sheers discovered his own personal mark? Many of his poems explore themes of loss or sadness, and some of them deal with pain such as World Maps. But none are as raw or unguarded as one might hope of a serious writer. His work can be wonderfully un-bordered; taking us from continent to continent, tenderly and skilfully unravelling the threads of intimacy, confronting the human condition, and peering between the brighter lines and graphs to source the black expanses of human suffering. But what about the landscapes of his own heart? Sheers is, undoubtedly, quite brilliant at translating and transcribing the pain of others. But I ask the question – will he ever fully master the articulation of his own?

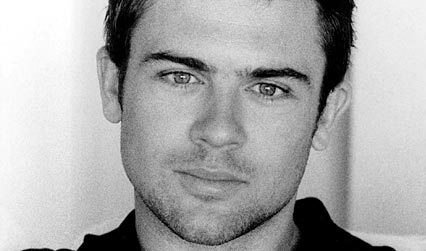

Owen Sheers is the writer of several poems including Pink Mist and World Maps.

Helen Calcutt contributes regularly to Wales Arts Review.

For other articles included in this collection, go here.