A new series in which we ask Wales’ top writers to share a glimpse of their work space. In this first instalment, Man Booker-nominated and two-time Wales Book of the Year-winner Patrick McGuinness welcomes readers into his clutter.

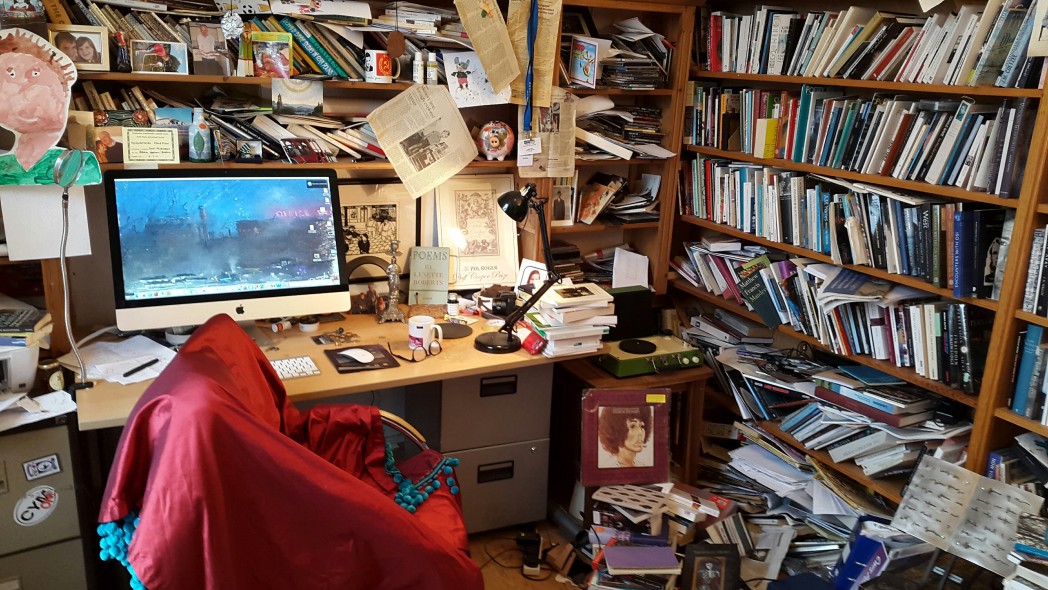

This is my study in Caernarfon. I think and work amid clutter, but this is where the clutter is contained. The room is at the front of the house, and faces the Menai Straits by way of Menai Motors, a car dealer’s forecourt. Menai Motors is run by a man called Dylan Thomas: how could I not buy from him?

I read several books at once. On the left is a copy of Marcel Lecomte, a Belgian poet and art critic, friend of Magritte and a wonderfully gentle, modest, writer who celebrates the ordinary spookiness of urban life. On the right, a pile of books by Georges Perros, Paul de Roux and Henri Thomas I’m using for a chapter about the everyday. There’s also Gilles Ortlieb’s Meuse Métal, etc., which I have by me a lot right now as I’m translating him. On the floor, by the Elaine Brown LP, is a stack of Orham Pamuk, on whom I was supposed to finish an article by 1st November. It’s in French, and the French are more elastic about deadlines than we are. I hope.

I like mess and I like noise. It’s important for me to hear things, look at things, pick things up and generally be able to stop, fiddle, make coffee, check the news, and generally procrastinate – but in a focused way, if that isn’t a contradiction. Thus the horizon of the desk needs to be busy and full of distractions, without actually being distracting. There’s a beautiful copy of Lynette Roberts’s Poems, found in Oxfam in Cardiff for 3 quid back when I lived there. It’s interesting that Faber have returned to that totally assured, aristocratic design on recent poetry books: the cover that says ‘this book is so classy it only needs a name and a title’. There’s a woodcut by Vallotton, ‘L’Anarchiste’, and an ashtray from Capsa, the Bucharest restaurant I used to go to when I lived there in 87-88, and a half-used packet of night-scented stock seeds. There’s usually some dental floss around too, but I must be between packs.

My home town of Bouillon, in the Belgian Ardennes, is important to me. I still live and breathe it, even if I worry it’s become too much of a resource for me, a marketable commodity to be traded in a literary culture obsessed with identity. But the connection I have with the place and the people is at once visceral, in the sense of painful, sharp, tear-inducing; and, paradoxically, ghostly, unmoored, and less and less tangible. So I surround myself with objects from my lost childhood, from the days when I was much younger and still Belgian. My great-grandmother’s Jesus candlestick is one of them, and stands amid the ink-bottles, photos, tiles, pens, loose change, loom bands and bits of slate, oddly resembling Christ the Redeemer as he oversees the eclectic jumble of Rio.

The screensaver is a pastel by my friend the artist Guy Ducaté, of Brussels Luxembourg station in 1955. It contains for me all the muted blaze and romance of rail travel and of train stations: from the small, curtailed local stop to the great ramifying capital city.

There are photographs and newspaper cuttings, a Ceausescu mug, some hotel toiletries, and a beer bottle my father painted of a Magrittian sky: half the bottle is day, half is night. He put much of his thwarted creativity into things like that: just above is a doorstop he painted painted to resemble an old-fashioned cricketer, complete with blazer and cap. Outside the frame there’s a whole team, made out of differently-sized screwdriver and toilet chain handles. Nearby is a certificate declaring that ‘Paul McGuiness’ won third prize in the vegetable plate competition in the North Wales Show in 2011. I garden, seriously and sometimes even proudly, so it’s not an ironic display. The only irony is that I haven’t bettered that ranking since.

Providing an example of bathos, but in reverse, there’s a photo beside it taken by my partner Angharad of me and the children by the grave of Hedd Wyn this summer. I placed it there after watching Y Daith Ewro 2016: Allez Cymru on S4C the other day, tracing the journey of Chris Coleman’s team to next year’s championships. The scene where they went to visit the grave of Hedd Wyn after their Belgian game moved me and made me pleased and proud to be Welsh by election. I took my son Osian to watch the next Wales/Belgium match, where Wales won and when it started to become clear they’d (we’d) qualify and might even finish top of their (our) group. The connectedness of my old world and my new one was symbolised by the fact that as we cheered there, in Cardiff, watching the match, my cousins were at home in Bouillon watching the game on TV, with a commentary by Philippe Albert, the great Newcastle and Belgium footballer, who happens also to hail from… Bouillon, and who I used to know when I was my children’s age.

Patrick McGuinness is a British academic, critic, novelist, and poet. His works include Throw Me to the Wolves, The Last Hundred Days and The Canals of Mars.

Photo Courtesy of Patrick McGuinness

Patrick McGuinness’ Writers’ Room piece is a part of a Wales Arts Review series.