In the next instalment of the popular Writers’ Rooms series, novelist and poet Richard Gwyn gives us a peak into his Spanish workspace.

I am fortunate in having two rooms to write in: one is the loft of our Grangetown home, from which I can hear the wheeze of approaching trains and oversee movement on the platform at Cardiff Central station; the other, far less cluttered, is pictured here. It is the basement of a house in Rabós, a small village in the Alt Empordà region of Catalunya. I am split between two countries, and two homes. It is a privilege, of course, but I run the risk of feeling as though I am permanently coming up against my own absence. I am a little obsessed by this idea of doubles or multiple selves, like Orhan Pamuk in his childhood memoir, Istanbul. My partner, Rose, says I have a Spanish and a Greek persona as well as a Welsh one. As a translator, I live between languages, so living between identities is only one step beyond. Sometimes this can be fun, at other times a little confusing.

Many years ago, this room was where the animals lived. It is the oldest part of the house, and I was told by a local architect that a stone arch connecting this room to the main entrance was around 600 years old. The space which my desk occupies was once home to a donkey – the owner pushed hay through a hole in the floor of what is now my daughter, Rhiannon’s bedroom, directly above – and there was a circular stone storage space for wine off to the left. There was also an olive press and a feeding trough. Off to the right of the picture there is an underground well, which, after much deliberation, we decided to cover. The house is called Can Font – the house of the source. As such, it might be expected to augur well for the flow of ideas.

It seems to me that memories and thoughts – possibly all the ideas you’ve ever had in a place, including the ones you don’t remember – hover like an aura or ambience in a room, and that once installed in your chair, a sort of silent buzzing surrounds you, and if things go well, you are absorbed into that silence and the memories or fragments of thoughts return to you. When work is going well, I think there is nowhere I would rather be than here. The chair is new: I had to go to an office store in Figueres, our nearest town, to buy it. It has ergonomic features to protect my back, and although not beautiful, it is very comfortable.

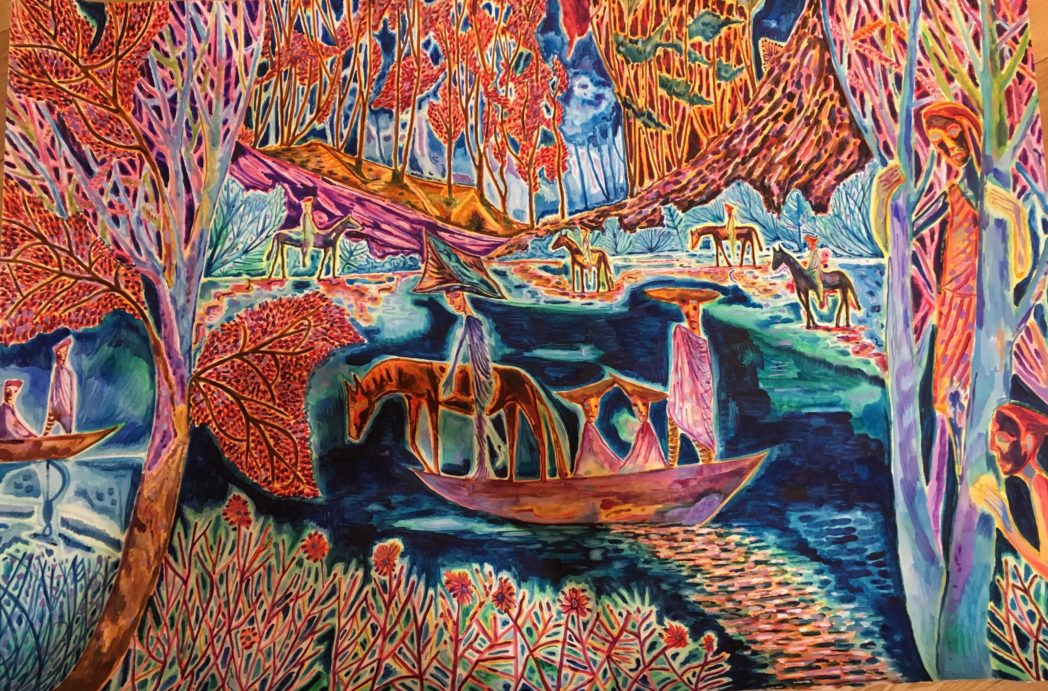

In this photo, a significant element is missing: Bruno, an elderly Springer spaniel, usually lies plumb centre of the room, which is the coolest place in the house in summer. Above the sofa is a large watercolour by the Welsh artist John Abell, called ‘The Smugglers’, which, by a circuitous route, has local significance. The village is connected to a smuggler’s track across the Albera mountains into France, and has always been a place of transit, most notably in the final days of the Spanish Civil War. The 19th Century French artist Jean-Baptiste Corot did a painting, also called ‘The Smugglers’, which features a rider wearing a red Catalan barretina, and on which John’s painting is based. John’s version has a Central or South American feel to it, which is also appropriate, given my own literary interests.

Above my desk is a miniature in a gold frame, of a human head bursting with tiny coloured particles, perhaps representing an explosion of idea or else an LSD trip. It is by Lluís Peñaranda, now passed away, but once my closest friend and the person who introduced me to this region in the 1980s. The painting is dated 1975, the year of Franco’s death.

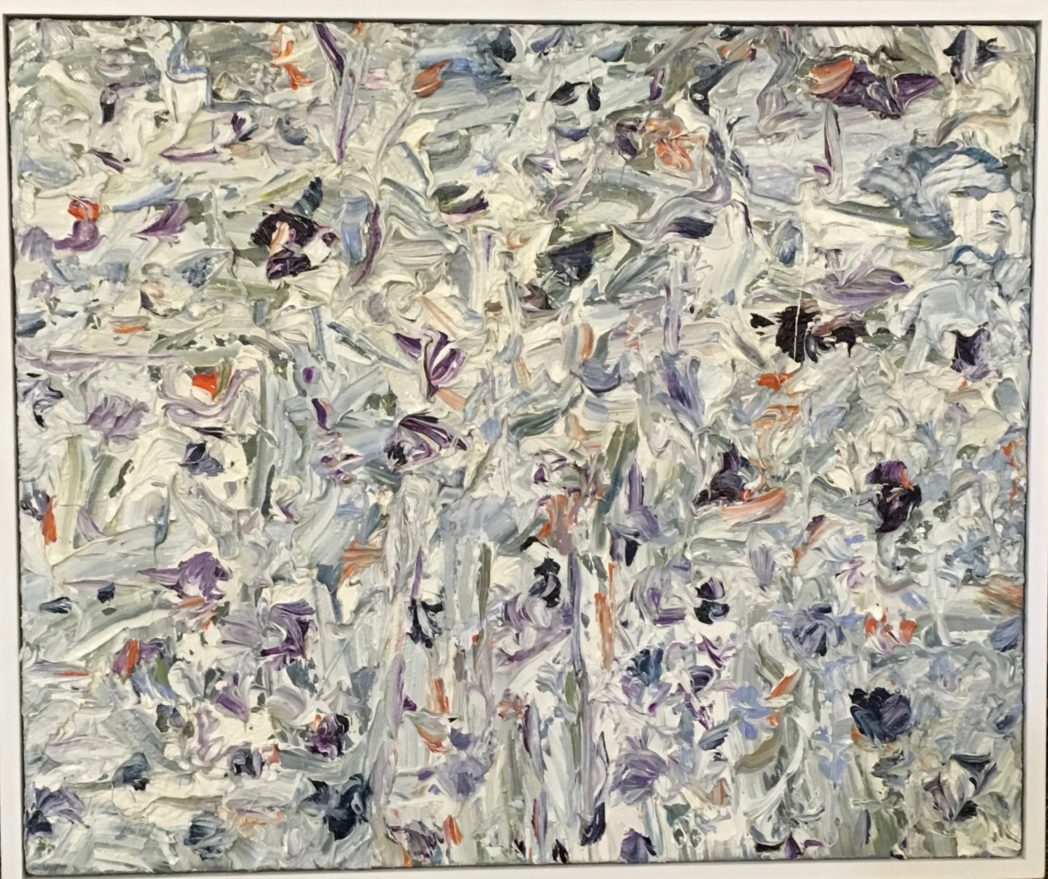

Under the light tunnel at the end of the room is an oil work, ‘Shimna’ by André Stitt. I love all three paintings.

Because the room is mostly below ground level, light was always going to be an issue, but the tunnel provides an ethereal glow, lending the room a kind of translucency which suits it well. But much of my work gets done in the dark, in the very early hours, at which time I rely on the dimmed ceiling lights and a desk lamp.

Usually Bruno the Dog stumbles downstairs with the arrival of daylight and settles patiently until I’m ready to take him for his morning walk, by which time I will have been at work for three hours or so. That is as much raw writing as I can manage in a normal day. During this early morning session I sometimes play ambient music; this year it was mostly William Basinski’s compositions 92982 and Melancholia. Nearly all my books are associated in my own mind with certain pieces of music. I always wanted to be a composer when I was young, and sometimes I think in musical phrases, a kind of synaesthesia, I guess. Around nine o’clock I walk Bruno and then have breakfast with Rose. I return to the desk and edit, revise and re-write until early afternoon, when I break off. Revision is for me the best part of writing, and most writing is re-writing after all. The process also involves reading, research, and a lot of coffee. On a good day it feels as if the resistance, struggle and angst that inevitably accompanies a first draft is vindicated by the sheer exhilaration of rewriting.

Usually Bruno the Dog stumbles downstairs with the arrival of daylight and settles patiently until I’m ready to take him for his morning walk, by which time I will have been at work for three hours or so. That is as much raw writing as I can manage in a normal day. During this early morning session I sometimes play ambient music; this year it was mostly William Basinski’s compositions 92982 and Melancholia. Nearly all my books are associated in my own mind with certain pieces of music. I always wanted to be a composer when I was young, and sometimes I think in musical phrases, a kind of synaesthesia, I guess. Around nine o’clock I walk Bruno and then have breakfast with Rose. I return to the desk and edit, revise and re-write until early afternoon, when I break off. Revision is for me the best part of writing, and most writing is re-writing after all. The process also involves reading, research, and a lot of coffee. On a good day it feels as if the resistance, struggle and angst that inevitably accompanies a first draft is vindicated by the sheer exhilaration of rewriting.

Of course, not all days go to plan, and sometimes I sit for hours without doing much at all, wasting time, if indeed time can be wasted. I have a favourite poem by Adam Zagajewski that describes this state perfectly. It is called ‘The Early Hours’ and evokes that sense of sitting at one’s desk at five in the morning, in the benign silence that precedes the day: ‘The early hours of morning; you still aren’t writing / (rather you aren’t even trying), you just read lazily. / Everything is idle, quiet, full, as if / it were a gift from the muse of sluggishness . . .’

Richard Gwyn’s latest novel, The Blue Tent is available now from Parthian

Richard Gwyn’s Writers’ Room piece is a part of a Wales Arts Review series.