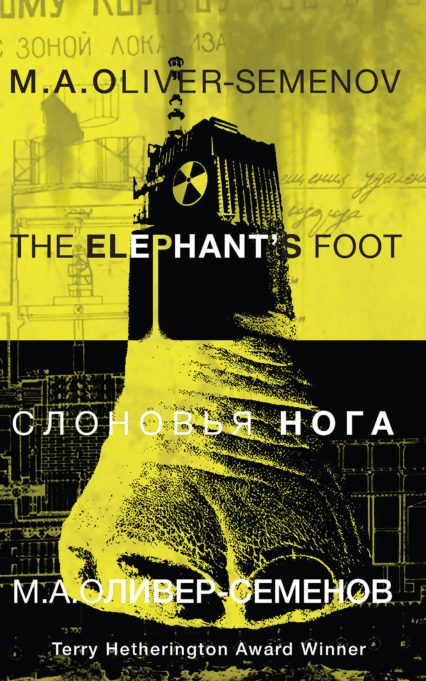

Published poet M. Oliver-Semenov details the creative process and the struggles behind putting together his poetry collection The Elephant’s Foot.

Facebook duly notified my yesterday that it is seven years since my first publication. Seven years since I secured one poem in the Parthian anthology Nu Fiction and Stuff; seven years since I went to the Hay Festival for the very first time, drank too much, pee’d on the ice cream stall, spent a week in the green room drinking it dry, and pulled an all-nighter in a pub pretending I was famous. That week of extreme highs and extreme lows was my initiation into the world of publishing. One poem published and I was an addict. ‘Peace Crane’, the poem that bought me that week of debauchery went through no fewer than sixty-three edits. The version in The Elephant’s Foot is the sixty-fourth.

This however was all an accident. ‘Peace Crane’, the catalyst to this collection was born through love and shame. In 2006 I was doing odd jobs for a living, had no fixed income, and I knew it was only a matter of months before I could no longer afford my rent. It was during this time that I began a doomed love affair with a PHD student from Cardiff Uni. She was never going to stay, not with a bum like me. Although I was doing regular night club slots with hastily written performance poetry, I had no credentials to speak of; no degree; nothing on paper; nothing that came with a cover that had my name on it. My girlfriend had started school a year earlier than other children, began and completed high school a year early, finished a master’s a year ahead of everyone and was now on course to finish her doctorate early too.

It wasn’t the end of that relationship, but her kind and selfless encouragement that shamed me into trying harder. If this successful scientist could see something in me, then maybe I should quit fucking around with the instant gratification of evening applause and aim higher. There are several poems written about that love affair in my collection. They are not written through bitterness, but affection.

After I had recovered from my Hay-on-Wye hangover, I went on a frenzy of submitting here, there and everywhere. I had tasted success and wanted more. This led to my first residency in a magazine: Blown – the journal of artistic criticism and cultural intelligence. Unpaid of course, but I didn’t care. I thought I’d made it. I hadn’t. Within two years it folded and all I got was a couple of toasted sandwiches and a pint of beer. But that experience really helped to sharpen my writing and widen my perspective. I wrote some of my best poems for Blown – though none of them are in Elephant as they were all commissions tied to photo-documentaries. After that residency I again began a submission frenzy. I made charts and ticked off magazines as the acceptance or rejection letters came in. I submitted randomly and without organization. It was a mess. And it was foolish because I wasn’t sending poems that I thought were suitable for their target journals, I was just trusting to luck.

Sometimes I got lucky, but more often than not I found that my sloppy methods and lack of research led to ‘thank you for sending us your work but…’ Although, of the one hundred and thirteen poems I had by that time were good, many of them weren’t edited or redrafted. I was sending stuff out on draft one to feed my lust for seeing myself in print. This had to stop. I had to sit down and remind myself of why I wrote poetry, who it was for and whether I deserved to be published in the first place.

I did not abandon the idea of a first collection through rejection or hopelessness, I just stopped chasing it because I knew I was writing and seeking publication for all the wrong reasons. I was vain and a collection published then would have reflected this. I had to fall in love with writing again and to be sure that my focus was on quality of verse. It’s not that my poems were bad. But they weren’t crafted. I was in too much of a hurry.

When I moved to Russia in 2012 I had no intention of ever sending another submission again. I wrote poetry but it was for the sake of writing poetry. I had matured. Seeing my name in print meant nothing to me. Poems came first. The quality of verse came first. Every word mattered like it had never done before. It was less than a month after settling in Siberia that Parthian offered me not only a contract for a memoir but for a first poetry collection also. And so it was only when I had grown enough as a person and a writer not to give a shit about publishing again that opportunity arrived. This was the right time. If I had been offered a contract any time sooner the writing would have been substandard. I suppose publishers know this. They keep their eye not only on what newbies are publishing but on what they’re not publishing too. I had gone away, left, said goodbye to the race-to-be-in-print, my family, my country – everything I had ever known.

Is it only when you’re willing to walk away from something that you become worthy of it? Is it only when you’re willing to say goodbye to someone that you become worthy of their love? I don’t know but I think there’s something in veering towards yes.

When I had signed both contracts it was Sunbathing in Siberia that had to come first. I had already completed three chapters and Parthian were keen to release a memoir that year. Though both books were scheduled to be released in 2014, it soon became clear that Elephant had to go on the back burner. It was too much work – focusing on two books at the same time, prose and poetry, was a little bit too ambitious. So Elephant was put off until spring 2015, then autumn, then 2016.

I am really happy about this. Each delay allowed me to add something to the collection that I now realise was essential. Though I normally only write between one and five good poems a year, a burst of creativity in 2015 gave me twenty. Almost all of them are included. Elephant really wouldn’t be complete without them.

When it comes to poetry there is something to be said for taking one’s time. There is no rush. If a poem takes one day or one year to finish it does not matter. It is not a race or a competition. A poem is only finished when it is finished, and most poets will agree that a poem is almost never finished. The same can be said of poetry collections. When I discussed a first collection with another publisher back in 2010 I was told that most poets have to publish in journals for around eight years continuously before they are ready for a full collection. I took seven. I am a year early. This doesn’t mean that Elephant is premature. I wouldn’t release it now if I felt so. I care so very little about seeing my name in print these days that I wouldn’t hesitate to delay it another year or even another ten years if I felt it wasn’t ready.

But it is ready. I don’t know when the next one will happen or even if there will be a next one. If I don’t publish another collection for fifty years, or ever again, it’s fine. The Elephant’s Foot isn’t here because I feel a need to be somebody, it’s here because I feel I have worked on the poems and edited them to a point I cannot go beyond; they are ready to be set free.

As with Sunbathing, before editing even began, I asked Susie Wild, who is a friend as well as my editor, to be completely brutal; to the nth degree. She was. We both were. She cut a dozen and sent the file back to me, then I cut a dozen more. There is nothing in Elephant that I don’t wish to be there. If I had any doubts at all I pressed delete.

When I was in college, my lecturer, Mr. Hugh Lester, taught me that in order to create something, you begin with a good idea. You write it down then build a book or a poem around it. What you then have to do is be willing to do it cut out the original idea or first line because it is no longer in keeping with the rest. It was the seed, and the seed has to go into the fire. My editor and I cut and burned over and over. What we’re left with is a collection, a first collection, where every word has been weighed twice and twice again. There’s nothing I would change. All the seeds went into the fire.

How I Feel Knowing the Kind of Pornography You Watch

In your most intimate moments alone

it is not my face you picture.

So do you see me when we are alone together?

You don’t, I know; eyes always closed.

I’m supposed to say that it’s alright,

it’s perfectly normal and I don’t care.

But you should know that I have come to crave

a solitude so deep, that even I am not there.