Ahead of a performance of Harri Gwynn’s Y Creadur, Robert Minhinnick talks us through the process of translating a forgotten Welsh, poetic masterpiece.

I thought writers loved libraries. Maybe they still do. I learned to love the old Carnegie-bequested Bridgend library, opened in 1907 in Wyndham Street. Threatened now with closure, it hasn’t changed much. Last year I published a letter agreeing with the campaign to turn it into an arts centre. Maybe that will happen.

For me, it was either the reading room or the poetry shelves. My mother would have asked me to look at the biographies (especially of the ‘Bloomsbury Set’, with which she was fascinated) or astronomy. But in those days science and history always seemed like work to me. I’ve been failing to catch up ever since.

No, it was poetry that I browsed, usually hardback, although I seem to remember some paperback Peter Redgrove. And gradually I began to take out Welsh language collections, as I tried to improve my feeble grasp of the language. None of the poetry was popular, the Welsh especially unloved.

Yet studiously, I tried to translate whole poems. Maybe this is an indication that Welsh was a foreign language to me, although I didn’t feel that way and don’t now. So I puzzled over Bryan Martin Davies, Dafydd Rowlands, Einir Jones – anybody who didn’t look too daunting and whose volumes were found on those sparse shelves.

Years passed. Then a letter arrived asking me to join a team of writers translating poems for the proposed Bloodaxe Book of Modern Welsh Poetry, due in 2003, edited by John Rowlands and Menna Elfyn.

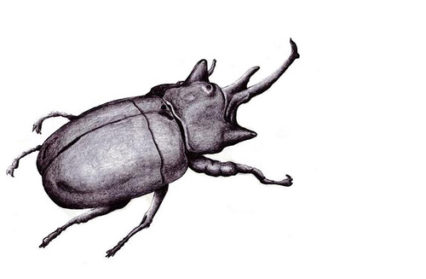

Sion Eirian was the first poet. He was my age. Not impossible, I thought. Then a host of others. As I worked I gained confidence. Maybe I was even enjoying the commissions, although I was supposed to be editing Poetry Wales and helping develop the charity ‘Sustainable Wales’. Then, one morning, Harri Gwynn’s Y Creadur arrived.

Now, in this year of his centenary, Harri Gwynn is overshadowed by R.S. Thomas, and in 2014 will be overwhelmed by the Dylan Thomas industry. That’s life. Some of Harri Gwynn’s papers can be found in the National Library of Wales and are said to include English and Spanish notes towards Y Creadur, a long poem in free verse (pryddest), controversially overlooked for the Crown at the 1952 National Eisteddfod. I did not consult these papers when making my version of his pryddest.

The way I’ve translated Harri Gwynn stresses his ability to create characters in his poetry. These days the people I’ve depicted in Y Creadur might be seen as soap opera archetypes. ‘Minnau a adwaenwn yr wynebau, / Rai. (Here are some of those faces / I recognise’) writes Gwynn, and indeed he makes a gallery of them.

For me, these characterisations are necessary for humanising an otherwise long and exhausting poem. Possibly Y Creadur reveals or even celebrates a fear of female sexuality and supposed duplicity.

The great relationship of Gwynn’s life was with his wife, Eirwen, a scientist and prolific writer. Together they were a formidable couple, politically adventurous, especially in feminism and linguistic matters. Eirwen published a celebrated account of their life together, ‘Hanes Dau Gariad’ (Gomer) in 1999.

Harri Gwynn was a writer before he became famous in Wales on the nightly news programme, ‘Heddiw’. Yet there is surely a journalistic element to his poetry. Unsurprisingly, he was also a prolific author of short stories.

For me, translation has developed a long way from those days in Wyndham Street. It now provides an opportunity to remix or rescore poems I admire or find intriguing. In this way, I see translators as able to become experimental composers and musicians.

Because for me, translation should be imaginative and always based on music. Otherwise it can prove a mere dogged copying from one language into another. Why do it?

Before I was asked to translate Y Creadur, I had never heard of Harri Gwynn. My attempt to make a ‘version’ of Y Creadur is described in an essay in Poetry Wales (49:2) issued October, 2013. As to that huge Bloodaxe volume , it is full of poems probably accurately translated into English. But mostly it fails to catch fire. The collection is dutiful but too many of the translators were intimidated by the idea that Welsh is ‘the senior language’ in Wales. Thus they avoided risk taking.

When I look at my version of Y Creadur now, I hear music: erotic, disgusted. I think of The Velvet Underground’s ‘European Son’ or ‘The Black Angel’s Death Song’, with John Cale’s atonal viola to the fore. More complex and ambitious than those pieces, Y Creadur is one of the darkest and disturbing poems I have ever encountered.

On October 30, ‘13 in The Studio, Aberystwyth Arts Centre, there will be a public reading of ‘Y Creadur’ by Twm Morys, and I will premiere my version, ‘The Creature’. Twm will explain why Harri Gwynn is on his ‘hero list’. I might get the chance to talk about the idea of ‘translating’ as ‘music’.