As I travelled to Wales, the mountains of Snowdonia were three brushstrokes floating in the haze above the horizon. Arriving at my base on the coast, the abrupt change of landscape from my inland home fired neurones that had been dormant; a new chemistry rushed through my mind. The sea fell away to a vanishing point, taking my vision further than it had been for months. The air was cool and moist despite the warmth of the day and revealed my breath, taking my inner self into the landscape and renewing my soul as the sun sank without the merest hint of fiery protest.

The morning was as calm as the evening before, the flat sea livened by a thousand points of light, passing through the air scented by stranded seaweed and full of the sound of the sea lightly beating the rocks that tilted back from the water, grey tan to black. Rays fanned out in a mottled sky, reflected by a cliff-top pool backed by a standing shard of rock. Oystercatchers cried, short-lived Catherine wheels coming to a halt as languid herring gulls spiralled over the bay, others called in despair as time tried to stand still.

Walking the rivers of human habit along the cliff-top, there were bursts of yellow gorse flowers against the teal-blue sea and outcrops of lichened rock needled the sky. Nearby, the crisp lines of the wheatears, grey and black arc of wing, peach breast and black eye line. Further gulls and jackdaws were on the cliff faces, and primroses and buttercups clung on above. A jackdaw moved from post to post, with a grey snood and a white eye bereft of empathy. A raven floated back and forth along the cliff-top, on occasion bringing its wings in and rolling upside down in what seemed an enjoyable romp.

I travelled inland to Cwm Idwal, the hanging valley. Cloud gathered behind Devil’s Kitchen, but it was still bright as I set out. As I walked I tried to understand the timescale of the mountain’s living. The trees like gnats on flesh to this geological being, each tree a blink of an eye to the mountain. The lichens the only life that can begin to understand the mountain’s time. Not wanting ascent to dominate my destination, I skirted the base of the mountain and felt the firm resistance that felt somehow hollow beneath. I walked up to beyond where trees can grip its side, but the skylark still sang, describing the crags. Then, like many others, I pitted myself against the slopes towards Llyn Idwal and the summit of Y Garn, a place to take in the landscape, not defeat it. It was good to push against the slope and feel the force of the mountain’s gradient. From the summit I saw people cradled in the landscape. We gather where nature is most kind; below the hills, on the level where there’s water and shelter from prevailing winds. Here, landscape, nature, time and human meet to form place.

As I descended I listened to how the mountain spoke, in many simple tongues, each streamlet a whisper and the fledgling becks surrounded me. Each step revealed a different voice describing different points of the mountain. As I sank into the valley, I held the rising moon constant on a ridge. Whilst I adore this place, it can induce a certain melancholy. The pyramid-shaped Pen yr Ole Wen dominated the view to the northeast as the gunmetal grey slabs lay obliquely behind me. Once beneath them, surrounded by 270 degrees of steep sides, the term amphitheatre belittles the power of this place. The open end revealed blue sky, but there was no sun here and the wind blew cold. I tucked myself in, away from the wind, up by a six-foot waterfall looking out at the dark pyramid mount to the left and onto the sloping slabs to the right, the place where my father had learned to climb. It started for him with a school trip to Snowdonia in 1947, which made him think about the big rock faces, and in 1948 aged 14 he returned alone by bicycle from Manchester for his first rock climb:

Idwal Slabs where many young persons climbed, the Ordinary Route up the centre of the face, easy, good holds which led up to a traverse about 200ft then a steep wall above. I had a pair of boots by now with climber nails in. My memory of that day was that the boots must come off in order for me to climb the wall above me, so up I went with boots around my neck, this was hard and took me quite some time. On descending to the valley I looked up to where I’d been, I couldn’t believe it.

This awe and mastery of nature is one part of our innate connection to it. I gripped the rock, the rock on which my father had depended many decades before, to be connected like the birch that clung to the boulders above the stream where the rowan once stood. When one becomes familiar with the landscape it can tell of stories past. The landscape becomes an external memory in a shared mind, each haunt a scene full of cues; many cues, as leaves on a tree. Each path, boulder and tree, each flower, grass and bird, is connected to another time. Each scent and reflection, each cloud and gust of wind, both a present connection and memory weaving your self into the landscape.

I continued, without destination, hearing only the wind. I felt that I was walking through my mind, rather than the landscape. I slowed to a mindful pace, feeling each breath, and then a feeling beyond the limits of my language engulfed me and I wished that I could plant words as seeds. As the beat of rain became apparent the mountain seemed to reflect my condition, like a mirror of the mind. I stopped and I stood in the landscape, until only the landscape remained.

Dr Miles Richardson (@blackbirdsyear) is an applied psychologist and ergonomist researching our connection to nature. This research interest grew from writing on foot while reading nature’s story – the act of writing is not simply an output of thought, a substitute for speech or recording of knowledge: writing enables and shapes our thinking. A Blackbird’s Year, published Autumn 2014, is a story of unearthing a unity of life, mind and nature: www.milesrichardson.co.uk

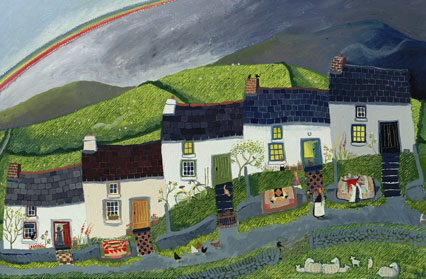

Banner artwork courtesy of Valériane Leblond – ‘Does dim dal’