Susan Morgan used to find the marked difference in approach to the plague years of Daniel Defoe and Sicilian-born sculptor Gaetano Giulio Zumbo difficult to relate to, but here she explains how the emergence of the current global circumstances has helped her reappraise the work of the two men, and to find messages of kindness.

Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (published in 1722) was described by one reviewer as ‘the most lively picture of truth that ever proceeded from the imagination’. An unflinching account of the effects of the bubonic plague in London in 1665, it combines fact and fiction. Mounting mortality figures gleaned from Parish records are juxtaposed with scenes that chillingly evoke the psychological effects of a sudden exposure to death and disease on a mass scale, framed as eye-witness accounts.

A female body is glimpsed through the upstairs window of an otherwise abandoned house by two watchmen who climb a long ladder to investigate, seeing her ‘lying dead upon the Floor, in a dismal Manner, having no Cloaths on her but her Shift’. When the Magistrate, having been informed, gives permission for the house to be broken into, ‘a Constable, and other Persons being appointed to be present, that nothing might be plundered… no Body was found in the House, but that young Woman, who having been infected, and past Recovery, the rest had left her to die by her self, and were every one gone, having found some Way to delude the Watchman, and get open the Door…’ Many such ‘escapes’ were made to try to dodge the authorities and the disease, despite it being unlawful in a shared household, when one person was infected, for the others living there to leave the house without a Certificate from the Examiners of Health of the Parish.

A female body is glimpsed through the upstairs window of an otherwise abandoned house by two watchmen who climb a long ladder to investigate, seeing her ‘lying dead upon the Floor, in a dismal Manner, having no Cloaths on her but her Shift’. When the Magistrate, having been informed, gives permission for the house to be broken into, ‘a Constable, and other Persons being appointed to be present, that nothing might be plundered… no Body was found in the House, but that young Woman, who having been infected, and past Recovery, the rest had left her to die by her self, and were every one gone, having found some Way to delude the Watchman, and get open the Door…’ Many such ‘escapes’ were made to try to dodge the authorities and the disease, despite it being unlawful in a shared household, when one person was infected, for the others living there to leave the house without a Certificate from the Examiners of Health of the Parish.

Defoe’s account makes for grim reading. ‘Things were greatly altered. Sorrow and Sadness sat upon every Face’. The narrator, known only by his initials: H.F. and his profession: Saddler, restlessly roams the streets, recording all he sees. Yet this is no dry accounting of facts; he feels, as does everyone he writes about. ‘London might well be said to be all in Tears’. The tone darkens as the sheer number of deaths mounts up, when the response of the people changes. In the early stages of the plague the city is full of noises:

The Voice of Mourning was truly heard on the Streets. Shrieks of women and children at the Windows and Doors of their Houses, where their dearest Relations were, perhaps dying, or already dead, were so frequent to be heard, as we passed the Streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest Heart in the World, to hear them.

Towards the end, when ‘Time enur’d Them to it all’ such extreme expressions of emotion can no longer be sustained.

Men’s Hearts were hardened, and Death was so always before their Eyes, they did not so much concern themselves for the Loss of their Friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next Hour.

The more we read, the more we are affected, especially when we observe the mistakes that were made. As well as falling for quack remedies and false predictions, people infect their households by sending servants out to shop for the basic necessities: ‘Food, Physic – to Bake-houses, Brew-houses, Shops etc. [where it was] impossible not to meet with distempered people.’ For poorer people things were even worse, for they ‘could not lay up Provisions’ and were forced to ‘go to Market [themselves] to buy and others to send … their Children; and as this was a Necessity which renew’d it self daily; it brought an abundance of unsound People to the Markets, and a great many that went thither Sound, brought Death home with them.’ Nor are people always kind: ‘They did not take the least care, or make any Scruple of infecting others’ not necessarily because they are wicked, but because they are ‘People made desperate, by the Apprehensions of them being shut up’.

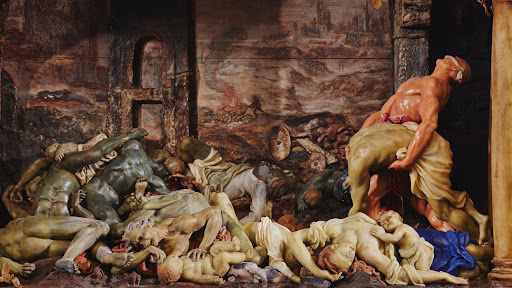

It was when I read (with horror) about great burial pits dug for the unceremonious dumping of bodies that I was reminded of strange dioramas, small glass cases containing dramatically posed miniature figures in nightmarish landscapes that I came across when visiting the anatomical wax model collection at the Museum of Natural History in Florence. Sicilian born Gaetano Giulio Zumbo, who lived from 1656 to 1701, is renowned for being an early exponent of ‘the art and science’ of wax anatomical sculpting for teaching purposes, but his three-dimensional ‘theatres’ have been called ‘macabre graveyard art’. One, thought to have been created when he lived in Naples, from 1687 – 1691, represents the human suffering caused by the bubonic plague in Naples in 1656.

Associated with Italian Baroque painting, his miniature wax figures have also been compared to figurative sculptures in Sicilian religious shrines and crypts connected with votive offerings and spiritual cures. Like them, some of Zumbo’s wax models are ‘dressed’ in pieces of cloth and decorated with necklaces and real human hair. The darkly painted landscapes in which they have been placed feature fragments of past architectural glories as well graveyards and grottos. Zumbo’s ‘little theatres’ – teatrini – depict human death and disease with such force they were shunned by many of his contemporaries, who thought them cursed. On the occasion of my visit to La Specola, when I was curious to see for myself how seemingly accurate anatomical details were combined with symbolic effects in life-sized wax Anatomical Venus figures, Zumbo’s tableaux seemed macabre and overly dramatic. Having read A Journal of the Plague Year during the Covid-19 pandemic, I now feel differently towards them, better able to understand their message.

The largest burial pit in Defoe’s account of the plague, described by his narrator as a ‘dreadful Gulph’, ultimately held 1,114 bodies transported there by Dead-Carts, under cover of darkness. Not only corpses; some people when infected ‘and near their End, and dilirious also, would run to those Pits wrapt in Blankets, or Rugs, and throw themselves in.’ Here H.F. pauses, as if for air, before admitting that words fail him. ‘This may serve a little to describe the dreadful Condition of that Day, tho’ it is impossible to say any Thing that is able to give a true Idea of it to those who did not see it, other than this; that it was very, very, very dreadful, and such as no Tongue can express.’

It is as an expressionist of the inexpressible that Defoe seeks to represent the effects of the bubonic plague. Shocking scenes are dramatically evoked, of persons falling dead in the street, along with ‘terrible shrieks and skreekings of Women, who in their Agonies, would throw open their Chamber Windows, and cry out in dismal surprising manner; it is impossible to describe the Variety of Postures in which the Passions of poor People would express themselves.’ Defoe’s fictitious journal was published in 1722, a year after the plague returned with a vengeance to Marseilles, which he reported upon for Applebee’s Original Weekly Journal. Statistical records (known as Mortality Bills) from the 1660s were reprinted that same year, amidst growing concerns that the outbreak in France might spread to Britain. Defoe includes examples of such numerical records in A Journal of the Plague Year to question their accuracy. Seemingly authoritative statistics and tables are juxtaposed with highly emotive scenes featuring families and individuals acting out all too human stories, to emphasise how unreliable they must be, because of the mortal dangers and practical difficulties involved in recording incidents of contagious disease and death on such a mass scale.

In his Plague diorama Zumbo adopted an equally expressive approach to his subject, with figures posed for maximum emotional effect to represent the horrifying results of an uncontrollable contagion that spreads across borders, affecting everyone, even those not infected. By drawing on sculpting techniques from classical art Zumbo manages to portray the physical human body at its most vulnerable, by emphasising the beauty and potential for life that is lost during such a crisis. Are these works by Zumbo and Defoe horrific? Undoubtedly, but understanding works from the past like these may help us to reflect on the fact that it is our biology that most connects us, which is why we need to take care of everyone in society: health and well-being are public, not private issues. They remind us what was most lacking then and also what is most needed now in our ‘dreadful Fright’: a well-informed, scientific response to our shared predicament, but also one that is based on enlightened social values like fairness, decency and kindness.

Dr Susan Morgan teaches creative and critical writing at Cardiff University and is currently working on a book on representations of the female body in anatomy and art.