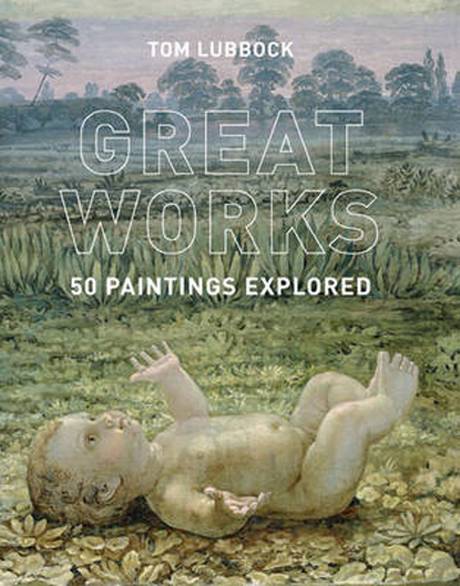

Adam Somerset reflects on Tom Lubbock’s remarkable work as an art critic through his collection Great Works: 50 Paintings Explored.

Tom Lubbock was chief art critic for the Independent from 1997 until his death in January 2011. He received news of the decision to make a book from his reviews-cum-essays two months before he died. His two years of decline, suffering a brain tumour, are movingly recorded in Until Further Notice, I Am Alive, published by Granta in 2012. The writings collected for Great Works: 50 Paintings Explored have the hallmark of a critic who is likely to endure.

Firstly, he looks deep into the works, but he also knows about things in the world. He knows about children, and how they first draw. The first attempt is invariably what he calls a cephalopod, akin to a tadpole. When Caroto paints a boy holding a drawing in 1515, Lubbock knows it not to be a child’s drawing but an adult’s representation. He knows that, on a woodland walk, human cognition cannot help from anthropomorphising the twisted shapes of fallen trees.

His vaulting range of suggestion outside the picture frame makes for exhilarating reading. He has read widely. He draws on Simone Weil to illuminate a fresco in Padua, on Bergson and laughter to spell meaning in a gaunt Sussex Down and chalk cliff by Paul Nash. Samuel Beckett’s Molloy is invoked for a vast Tintoretto in Madrid. Joyce’s Leopold Bloom is cited in relation to Ingres’ ‘Madame Moitessier’.

by Tom Lubbock

216pp, Frances Lincoln Ltd

The range of reference and comment swings between the learned and the demotic. A 1765 Bellotto of a ruined Dresden church is likened to the first movement of Carl Nielsen’s Fifth Symphony. But the intricate lighting of a Zurburan still life reminds him of a unique lighting effect devised by Hitchcock for the passage of a possibly murderous glass of milk in Notorious. A Gericault in Montpellier leads his thoughts to Joe Orton and an episode from Fawlty Towers.

The range of pictures is broad. The greatest figures from the canon jostle with names new to this layman. For Goya Lubbock chooses not horror but one of art’s most endearing dogs. Jeremy Moon, (1934-73), is represented by five blue semi-circles on a red surface from the Tate’s collection. But, even with the familiar greats he employs a sharpness of phrasing. Rembrandt can put the same into a hand and a touch as into a face; the key word is mercy. Klimt now has superstar status, but his ascent to object of want by billionaire mobile phone monopolists is relatively recent. The Klimtian image, in Lubbock’s eyes, ‘is a supremely consumerist art’ whose time started to come about in the 1960s ‘with their smart graphics, their overt sexiness, their psychedelic glow.’

Context, history, biography illuminate but they are complement to the power of the eye, not its substitute. Lubbock sees deep into the image, discerning elements that elude the casual eye. He explains why the inclusion of a tiny lark in a Van Gogh wheat field is crucial. He recognises patches of brilliant white on a Peter Doig tree trunk for what they are, not as points of glare but pure painterly display. Cotan in his most renowned still life, in San Diego, does indeed form a tiny isosceles triangle in the lower right corner. In his framing of a boat heading for shore Caspar David Friedrich makes out of the prow a perfect Gothic arch. Lubbock’s scrutiny of hue and shade on a single leaf of holly by Fernand Leger is relentless.

Lubbock wrote for a newspaper and there is a dash and deftness to his prose. He enjoys himself looking at Lautrec’s 1893 ‘the Bed.’ Of the Venetian genre of dramatic religiously-themed pictures: ‘There’s an atmosphere of hysteria. A Last Supper can feel like a train going into a tunnel.’ On a still life of four jars: ‘the treatment makes them tangibly solid. It makes them audibly solid.’ Those tentative, and irksome, uses of ‘maybe’ and ‘perhaps’ are absent. Degas’ small working clay models of dancers and bathers, turned into bronze after his death, are simply ‘the greatest sculptures of the nineteenth century.’

The proof of the robustness of critical writing is in its testing. It would have been revealing to learn how Lubbock viewed the recent Artes Mundi 5 – whether he might conclude that four entrants fail to pass one or more primary hurdles of aesthetic qualification. Great Works: 50 Paintings Explored was my companion for one undisputed work of art, in Cardiff’s National Museum. Gwen John’s ‘Girl in a Blue Dress’ from 1914 is a tiny piece, not suggested by the book’s illustration, an A4 of a picture. Tom Lubbock knows paint as material stuff. He can see that Gwen John’s artistic effect has been achieved by blanching every coloured pigment with white. That’s how it is with critics who do the job; through them, we get to see more.