James Lloyd explores an often overlooked aspect of Samuel Beckett’s career, his short fiction, which the author regarded as his ‘most important work.’

In the introduction to The Complete Short Prose, 1929 – 1989 of Samuel Beckett, the book’s editor, S.E. Gontarski, notes that Beckett’s short fiction has to a large extent been neglected, and not only in terms of readership, but also of its place in his canon and the short story tradition in general. Yet the timescale included in the title of the collection attests that Beckett’s creative output in this genre spanned his entire life. So why have they been neglected? Many of his short fiction pieces are nothing more than fragments and can be seen, therefore, as a testing ground for his ideas (maybe that’s why Beckett regarded his short fiction as his ‘most important work’.) However, it is not that straightforward.

It is true, as one critic, Christopher Ricks, observes, that the fiction in The Collected Short Prose does familiarise the reader with the philosophies that underpin Beckett’s novels and dramatic works. However they should not be thought of solely as a ‘passage’ into the landscapes shaped by Beckett, as if they are somehow easier to understand or less resonant. If anything, they are skillfully crafted to encompass succinctly the mental and physical topographies depicted in his novels and plays. They are, as William Trevor says in describing the nature of a good short story, ‘the distillation of an essence’ and makes omission of any of Beckett’s short fiction from The Oxford Book of Irish Short Stories (which Trevor edited) all the more absurd.

If Samuel Beckett’s short fiction can be considered ‘alien’ when compared to traditional characterisations of the short fiction genre it is ostensibly due to his writing style and the subject(s) (or absence of) represented. While it is true that Beckett’s short fiction is the narrative form he used to explore the preoccupations evident in his longer prose works, the work stands alone (and yet interdependent) with the novels and plays; they are a glimpse of the human condition through a Beckettian prism.

Though unreliable, idiosyncratic, darkly comedic, deracinated, self-conscious, and often inclined to vegetative states, all narrators or narration tend towards the oral storytelling tradition with a proclivity for aporia – Beckett told Patrick Bowles in 1956 that ‘speech must always be in relation to silence’. Indeed, the performance aspect makes sense as Beckett was considered a poet above all else and the adaptation of his stories and novels to the stage and on audio tapes by theatre artists and actors such as Jack MacGowran, Billie Whitelaw and Barry McGovern are a testament to these sensibilities.

Let us take one of Samuel Beckett’s short fiction pieces as an example. The Expelled (1946) appears first in a short story trilogy that includes The Calmative and The End (First Love, considered his finest piece of short fiction, was also written around the same time.) First published in France as Stories and Texts for Nothing (1945) by Les Editions de Minuit, this trilogy of stories have in common an unnamed first-person narrator, a character inexplicably discharged from a dwelling of some kind, a house, mercy hospital or institution, who seeks his own personal refuge in a world freighted with a kind of Becketttian slapstick.

In The Expelled, the eviction or expulsion of our unnamed protagonist mimics the parturition symbolised throughout the narration, borne out of his subsequent attempts to form a coherent identity from an ostensibly paternal home. Unhoused, as it were, the narrator’s attempts to ‘go on’ are thwarted by his inability to put himself into a viable relationship with the world and results in a series of absurd and often humorous encounters that perpetuate his degradation.

But the narrator is also exiled from the self, a stranger in his own skin, his own head, and the idea of home, of shelter – be it a house or the human skull – leave him suffering from what can be seen as classic Beckett angst: a mind struggling to know itself, the delight and torment of consciousness and the conflict between one’s primal instinct for self-preservation and the equally if not more ancient impulse towards the oblivion afforded by death. Here, I am reminded of Eudora Welty’s quote on the short story, of how it emanates from ‘emotions eternally the same in all of us: love, pity, terror.’

The thought processes of Samuel Beckett’s characters lilt between the want to go on being (fuelled by the fear of consciousness’ disintegration) and what Beckett termed ‘positive annihilation’ (fuelled by the torment caused by the prospect of an eternity of consciousness.) It would have been better then to have not been born at all, than for the unnamed narrator of The Expelled to remain in the pre-libidinal, pre-linguistic, amniotic ‘home’. Ricks cleverly uses a line from the novel Murphy to outline this point when he highlights the passage where Neary escapes punishment from the law by being deemed a lunatic:

Never fear, Sergeant,’ he said, urging Neary towards the exit, ‘back to the cell, blood heat, next best thing to never been born…’

In this case the ‘next best thing to not being born’ is the ‘amniotic padded cell’. The narrator jumps ‘of his own free will’ into a cab where he can ‘curl up into a corner’. He asks the driver to take him to the Zoo, ruminating for a moment on why he had chosen that particular destination before deciding that it must have been the likelihood of being ‘cabless’ (or expelled). The narration continues:

…my own person, whose presence in the cab transformed it, so much so that the cabman, seeing me there with my head in the shadows of the roof and my knees against the window, had wondered if it was really his cabin, really a cab.

Curled up in the foetal position is as good as it gets, for, as Ricks puts it, ‘there is nothing to compare with the ultimate asylum; there is no substitute for nothing.’

In a letter to Pamela Mitchell, Beckett wrote: ‘it is queer to feel strong and on the brink at the same time and that’s how I feel and I don’t know which is wrong, probably neither. So much possible and so little probable’. The province the protagonist inhabits in The Expelled is situated, so to speak, ‘on the brink’ between the ‘from, and not to’, on the edge of something, in the penumbral interspace that lies between the poles of cradle and grave, light and dark, words and silence, heimlich and unheimlich. Or, to put it in the words of the narrator of The Expelled: ‘lost before the confusion of innumerable prospects,’ and then later, ‘we may reason to our hearts content, the fog won’t lift.’

Welcome to the Beckettian universe: inhuman, unreasonable, and, ultimately, unknowable. Any attempt to make sense of it results in multiple meanings and endless speculation, ‘How describe it?’ asks The Expelled’s narrator.

In an interview with Patrick Bowles, Samuel Beckett said:

Within the universe, we perceive divisions, which we name. Within a universe called meaningless, I contrive to perceive divisions of the relatively meaningful. What is the meaning of the word meaningful under such conditions? The significant is reduced to a matter of what can be described, within the confines of our understanding, according to the structure of language.

Language proves inadequate in explaining an unknowable universe. If there is a meaning or a reality to be rescued from a meaningless universe, it is exactly that, ‘a meaning’ or ‘a reality’, workable only in its relation to a time-bound experience, a synthesis of the meanings projected onto the world (‘within the confines of our understanding, according to the structure of language’) and rescued from an ocean of Heraclitean flux.

Our identity is intimately linked not only with time, but with the spaces we inhabit within time.In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard describes the concept of Topoanalysis as ‘the systematic psychological study of the sites of our intimate lives’. He continues: ‘At times we think we know ourselves in time, when all we know is a sequence of fixations in the spaces of the being’s stability’.

What we inhabit as humans are contingent social constructs, fabrications or, as Beckett puts it, ‘divisions of the relatively meaningful’. In divorcing the narrator of The Expelled from the perfunctory trappings of everyday life, they are forced to confront the void, and, at the same time, satisfy the human need to make sense of an inexplicable world. It is this clash that gives rise to the absurd, when this very human desire for an explanation meets the unreasonableness of the world. ‘What is important’ Samuel Beckett says, ‘is to discourage the world from concerning itself with us.’

Samuel Beckett is adamant in this vision of the world. The narrator is made to sleep in a stable and share a cab infested with rats, he is dehumanised in his search for shelter. This search is also a search for identity. A shelter works to solidify memory and imagination, to suspend our identity in time and space. As Bachelard puts it in The Poetics of Space, ‘memories are motionless, and the more securely they are fixed in space, the sounder they are’, he continues:

The house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams of mankind […] In the life of man, the house thrusts aside contingencies […] Without it man would be a dispersed being.

Home, identity, and language are themes that constantly permeate ‘The Expelled’, encircle it, as if rotating through the protagonist’s mind. The concept of Time (in comparison to Eternity) can also be read as one of the story’s main threads. The narrator muses about the impossibility of returning to one’s past, the third person narration used to refer to the child he was reflects this. His past is ‘other’ to him. Not only that, but he is also unable to project a future onto his present. Both provide a sense of ‘doubling’ and, together with the anxiety the narrator feels on seeing his window open where ‘they’ could have spied on him ‘if they had wished’, brings us into the ‘province’ of ‘The Uncanny’, where familiar and homely can become just the opposite, insidious and threatening.

At the beginning of ‘The Expelled’ we learn that the narrator has returned frequently to this house ‘during these years’ despite his later admission that he ‘went out so little!’ His ‘familiarity’ with the ‘situation’, that of continually being turned out rather than daydreaming in gutters (although this is not to be ruled out), raises the question of why he keeps returning only to be thrown out again?

Several patterns emerge in this trilogy of stories overall and none more prevalent than that of repetition or recurrence in ‘The Expelled’. The narrator’s position at the beginning of the story, on the steps, (‘I did not know where to begin or end, that’s the truth of the matter’), can be seen as a metaphor for philosophy emerging in Beckett’s work. As Eric Levy explains:

Beckettian narration is an allegory of its own impediment. The recurrent pattern of expulsion seeking, falling, and temporary refuge alludes to narrator’s inability to tell a story that will let him end. Every journey returns him to the same need to go on.

This idea can be extended further if we see the narrator as a Sisyphean figure. Under the entry for Sisyphus in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, it is noted that in ‘solar theory’ the myth is used to explain the rising and sinking of the sun every day. This corresponds to the detail the narrator provides at the end of ‘The Expelled’, ‘When I am abroad in the morning I go to meet the sun, and in the evening, when I am abroad, I follow it, till I am down among the dead.’

This ‘compulsion to repeat’, a pig-headedness to live life on one’s own terms, can be linked to repression and the death-drive. The protagonist strives to re-establish the silence and inanimate state from which he has been prodded and for which the image of a house, or any other container, comes to symbolize as both homely and unhomely. The image of the house breeds a nostalgia for peace and harmony which the paternal ‘hat’ that follows him out of the door can be seen to represent, an idyllic childhood that embodies wholeness of identity, something that has ‘pre-existed from time immemorial in a pre-established place’, as the narrator puts it. But in keeping with the Freudian concept of the uncanny, the heimlich also turns in on itself to become unheimlich, and the narrative is suffused with underlying menace.

We find out that he was ‘humiliated’ and ‘mocked’ and later discover that his room will be ‘disinfected’. The combination of daydream and flashback borders on the phantasmagorical and plays out like a montage sequence. The hat sailing, rotating through the air, the bloated purple face of the father, the cradle and grave; all of that before we arrive once again at the nostalgic images of the childhood house, the blue smoke rising sorrowfully from the chimney, and the narrator’s address to the sky ‘where you wander freely’, is a scene reminiscent of the third stanza of Hölderlin’s poem ‘Abendphantasie’ (1799) that ends with a powerful Beckettian image:

as though my foolish prayer has disturbed it, the magic is disappearing, darkness is falling and I stand here lonely under the sky, as always.

What follows is his search for refuge, which is always, as mentioned earlier, bound up with identity – ‘I whose soul writhed from morning to night, in mere quest of itself,’ says the narrator. But then, if this world, according to Beckett, is always unhomely, both homely and unhomely depending on whether or not we choose to concern ourselves with it, how does one situate a home in it, never alone oneself.

We find something resembling an answer in Murphy (1938). Its protagonist has been living in a ‘mew’ for roughly six months and that very soon he will have to leave. (One might hypothetically consider this to be the case of the protagonist in ‘The Expelled’ prior to his expulsion. The journey from the ‘interspatial’ mentioned earlier becomes the ‘innerspace’ that starts with Murphy. In other words, from the so-called civilised world of frills into the ‘skullscape’, where ‘all the values of the world break down, as they should and must, if one is to see it honestly’). Taking Beckett’s use of the word ‘mew’ in Murphy and ‘den’ in the short fiction trilogy, by tracing the origins of both we can see that each is invested with the ambivalence both at the heart of the image of the home and the pessimistic philosophies that would underpin Beckett’s work and life.

For instance, a ‘den’, among other things, is ‘a place of concealment’, ‘a small cramped room or house (esp. squalid)’, ‘in children’s games: a sanctuary, home’, ‘a hollow place, a cavern (obsolete)’, ‘a haunt of vice or misery’. Of significance, in terms of Beckett’s ‘creative descent’ inward, as Gontarski puts it, ‘den’ stems from the Latin word ‘antrum’, meaning ‘a cavity or chamber that is nearly closed and usually surrounded by bone.’

‘Mew’ (v.t.), on the other hand, stems from the Latin ‘mutare’ (‘to change’), meaning ‘to shed or cast; to molt’, ‘to shut up; to enclose; to confine, as in a cage or other enclosure’; while ‘mew’ (v.i.) is ‘to cast the feathers; to molt; hence, to change; to put on a new appearance’; a place of confinement or shelter’, ‘a stable or range of stables for horses.’

In ‘The Expelled’, the narrator speaks of his trip to Lüneburg Heath, feeling that the word ‘lune’ must have had something to do with it. Beckett uses the word ‘lune’ in the original French which denotes the moon and traditionally used in literature and myth to symbolise madness, or the state of being hunted. Perhaps its most appealing definition is, however, as ‘a leash for a hawk or falcon’. For instance, all three point to a kind of creative and personal metamorphosis for Beckett, the conclusion of which was a vision he could feel at ‘home’ with, having spent years ‘molting’ and ‘unhoused’ as he was before and during the Second World War. The Beckettian aesthetic then comes into being with ‘The Expelled’, his first foray into the French language. The proto-Beckettian character is un-leashed, so to speak, ‘truly detached, homeless and historyless’.

Representing identity and harmony, ‘the home’ comes to embody the desire to escape from the narrow confinements of society and family that dominated Samuel Beckett’s early life, the subsequent search for freedom, and the fictive creations he began to write after the war. Even so, while Samuel Beckett’s fictional creatures ‘may exist free of all memories and social commitments, outside conventions, traditions, and even history’, as he noted after reading André Malraux, ‘It is hard for someone who lives outside society not to seek out his own.’

The narrator requires, first, a room to withdraw into in order to wander the Palaeozoic dimensions of the mind, to achieve an anonymous darkness, free of meaning and without consciousness, but to fear the disintegration of it all at the same time. Secondly, he requires food, for the mind cannot travel very far without it, dependent as it is on the appeasement of the body. Beckett reduces his character once again to the category of an infant. In his attempts to find refuge he finds himself drawn to containers or places ‘where nothing obstructs your vision’. Here, the mind (‘where you wander freely’) is clearly in conflict with the ills of the body (‘stiffness of lower limbs […] extraordinary splaying of feet’ – the latter description chimes with Beckett’s predilection for slapstick).

Interiority follows this disaffectedness with the outside world, an escape into the mind where ‘it is possible to recognize the dominance of the unconscious mind’ in the narrator’s ‘compulsion to repeat’, hence the skull as ‘The heimlich chamber’.

The conflict between mind and body worsens. As the narrator of ‘The Expelled’ sets off down the sidewalk, he seems not in control of his body. He resembles an automaton as he meanders, taking him into the more disturbing territory of the death drive, walking as he does on the road. ‘The streets are for vehicles,’ a policeman says and points him back onto the pavement.

In the final sections of ‘The Uncanny’, Freud draws attention to what has been considered ‘the most unheimlich of places’, and interpreting the cab as his ‘mother’s genitals or her body’, (as Freud puts it), we understand that ‘the prefix ‘un’ [‘un-‘] is the token of repression’. Nothing in ‘The Expelled’ represents the disquiet that infuses Das Unheimliche more than the cab, and perhaps the best indication of this are Beckett’s own words when he writes, ‘The thing I always felt most, best, in Proust, was his anxiety in the cab’. Soon after we learn that the ‘roof of the cab was on a level with [my] neck.’ Once again, parturition is symbolised and later still becomes more obvious, ‘[my] legs were still thrashing to get clear of the frame […] I pulled clear with both hands, in my effort to extricate myself’.

Each container in Samuel Beckett’s fiction of this time gets smaller and smaller it would seem, until home is, literally, where the head is. ‘We are alone. We cannot know and we cannot be known’, writes a Proust-influenced Beckett. In The Unknown Diaries 1936-37, and following a reading of Herman Hesse’s Demian: die Geschichte von Emil Sinclairs Jugend (1919), Beckett writes ‘the inevitable business about the journey to the self’, noting that, ‘journey anyway is the wrong figure. How can one travel to that from which one cannot move away?’ Human beings are ‘sunk in themselves’ and are unable to emerge from this space. Neither does Beckett’s fiction. In much of his later work, the ‘home’ becomes a psychical shelter in a spaceless psyche, ‘the plain in my head’.

Taking inward shelter will not lead to peace of mind. The mental architecture of Samuel Beckett’s spaces is never free from harm. The mind, aware that what it is, is not all it is, that it is, in fact, prey to ‘hidden psychical processes’, struggles for mastery over itself and its environment. As our narrator moves through the flickering light and dark, casting illusory images of continuity and progress onto a finite existence, in search of refuge, he comes to understand that the journey is destined to failure. Indeed, he may have known it all along: ‘The short winter’s day was drawing to a close. It seems to me these are the only days I have ever known […] just before the night wipes them out.’ This admittance prefigures the famous statement from Pozzo in Waiting for Godot (1952): ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’.

The zoetrope device is an appropriate symbol for the image of the home in ‘The Expelled’. Its images flicker on the wall of the mind, memories, echoes of the unconscious. Zoetrope, (from the Greek word ‘zoe’ meaning ‘life’) and ‘trope’ (meaning ‘turn’), together signifying, ‘wheel of life’, the cyclical nature of existence, ‘each back the way he came’, the slitted drum that spins, the illusion of animation on the inside wall of the drum that could be the shadows on Plato’s cave. This diaphanous interspace inside the zoetrope is also that which is lived in the head, where any reality of the outside world takes shape. Freud says the relationship heimlich takes to becoming unheimlich is neither linear nor inverse. In the case of ‘The Expelled’ it is as dependent on psychical conditioning, which, refigured by latent psychical conditions, endows the world outside it with uncanny sensations that, as Bachelard might put it, emerge through imagination and memory: ‘we bring our lares with us’.

In ‘The Expelled’, the childhood home is gone, it is, as already mentioned, ‘other’ to the narrator. He is unable to maintain its past in the present and his identity threatens collapse as a result. His search for a ‘home’ puts him in a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, he can achieve the peace and wholeness he craves, and on the other it creates anxiety as it means a restoration of the lack that had provided him with some sense of identity. In other words, his instinct is in conflict with itself. The self-preservation instinct of development and progress that is heimlich becomes unheimlich. Samuel Beckett once wrote: ‘I have no intention of going home, it’s not home, there is none’. Home is something the narrator in ‘The Expelled’ cannot give a name to in his situation: ‘You can hardly have a home address under these circumstances’, and his search for one is a palliative for an existence that is strange both inside and out.

The noted novelist and short story writer, William Boyd, in his essay ‘The History of the Short Story’ states:

The well-told story seems to answer something very deep in our nature as if, for the duration of its telling, something special has been created, some essence of our experience extrapolated, some temporary sense has been made of our common, turbulent journey towards the grave and oblivion.

Boyd could have been writing directly about the short stories of Samuel Beckett. His short fiction is capable of delivering an effect and provoking a reflection in the reader so powerful and complex that it results in a shudder of the mind. Embalmed in a culture that wants life explained and packaged into a neat theorem that we can download and store onto our smart phones or iPads, Samuel Beckett’s stories do not lend themselves adequately to summary, instead they tantalise the reader with nostalgia for something primal, something we can only orientate ourselves toward, familiar and yet strange, the very essence of being.

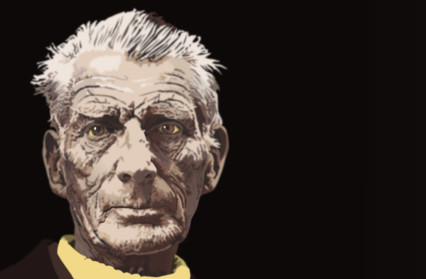

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

You might also like…

Nigel Jarrett reviews a collection of essays from Adam Somerset called, Between the Boundaries that range over art and technology, the world of beavers, the Hay Festival, and consideration of the benefits of war, among many other subjects.

James Lloyd is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.