The Music Room, Gregynog Hall, June 2016

Chamber Choir Ireland

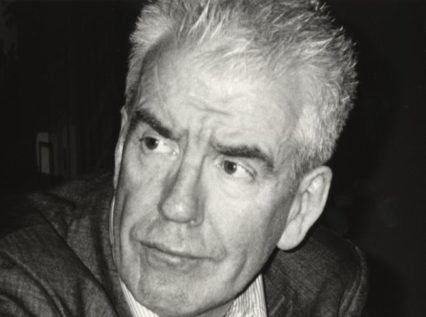

Directed by Paul Hillier

David Fennessy – chOirland

Charles Villiers Stanford – Three Motets Op. 38

Gerald Barry – Long Time

Stephen McNeff – A Half Darkness (British premiere)

Tarik O’Regan – Scattered Rhymes

Frank Martin – Songs of Ariel

arr. Paul Hillier – On Raglan Road

Coup and counter-coup seem all the rage in British politics these days – whilst the electorate is expected to make momentous decisions on the basis of too many of its representatives’ self-serving lies. Perhaps the greatest tragedy of Brexit is that it was an entirely faux rebellion in which ‘Leave’ protest voters were duped into aiming their political ire at the wrong target. In any case, the EU referendum turned out to be a deeply ironic backdrop to the poignant centenary commemoration at the heart of this year’s Gregynog Festival: the Easter Uprising in Dublin, 1916, in which freedom fighters attempted to ignite a widespread armed insurrection against the ruling British.

On Friday 24th we learned that the UK had opted to leave the European Union. Two days later, the Gregynog audience gathered for a final concert in celebration of the myriad cultural ties between the Celtic – and now soon to be erstwhile European – cousins, Wales and Éire. If there was one thing which brought hope, though, from Ireland’s turbulent modern history, and the wealth of shared heritage explored by Rhian Davies’s brilliantly curated Festival, it was that such ties ultimately run deeper than mere politics has the power to destroy.

Implicit in the imaginative, largely contemporary programme offered by Chamber Choir Ireland was the sense of an increasingly confident, artistically outward-looking Irish nation. Of the six composers featured alongside director Paul Hillier’s affecting arrangement of the well-known song, ‘On Raglan Road’, four were born in Ireland and one has close family connections, whilst Stephen McNeff was brought up in Wales: all have achieved international recognition – as has the choir itself under Hillier’s distinguished leadership.

The sixth composer, Frank Martin (1890-1974), is well-known to some but deserves a far bigger audience.* Born in Switzerland, he made his home in the Netherlands and proved a builder of bridges between French and German musical worlds, and between supposedly conservative styles and the serial avant-garde. Amongst many fine works, his 1950 Songs of Ariel sets words from Shakespeare’s The Tempest as its title suggests. Superbly crafted, with word-painting lending emotional sweep to an unshowy intensity, the five songs were beautifully performed here in a nod, too, to the Bard’s own 400-year anniversary. Such is the interweaving of history, poetry and music in the world beyond artificial borders.

But first, the concert opened with some very different, characterful new music. David Fennessy’s chOirland and Gerald Barry’s Long Time originated in CCI’s exciting ‘Choirland’ project: a collection of fifteen diverse works by Irish composers intended to showcase the vibrancy of contemporary Irish choral music. These two, short pieces proved well-selected for the programme at Gregynog, bringing a much-appreciated insouciant Irish wit to start the afternoon.

Fennessy has said of his music that “each piece is its own little universe” unrelated to other works, whilst Barry is known for his re-working and recycling of ideas from piece to piece. Both have produced adventurous snapshots for CCI. From the rhythmically energised ‘ha di-diddly-diddlies’ of the Fennessy to the equally mischievous, relentlessly rising and falling C-major scales of the Barry, we were taken from wordless ‘poetry’ to the deceptively prosaic reminiscences of Proust – by way of Beckett, Reich and a host of other (probably) tongue-in-cheek allusions.

Between these two, Stanford cut an altogether more serious figure in the closely-wrought melodic anglicanism of his Three Motets Op. 38 (written far earlier than their date of publication in 1905) – but without sounding old-fashioned, nor rendering inconsequential his modern-day fellows. More often associated with the Edwardian English-isms of his adopted homeland – whose choral tradition he did so much to reinvigorate – it is sometimes forgotten that Stanford was born and brought up in Dublin. Here the sheer quality of his vocal writing was apparent, thanks to the choir’s fine rendition of his gently ecstatic harmonies and unfussy polyphonic layerings.

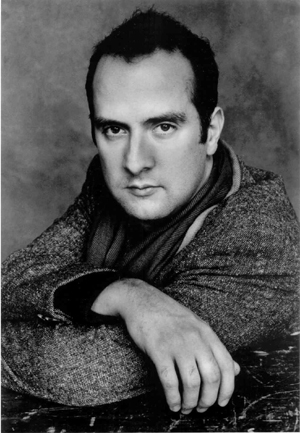

Vocally, regardless of the extremes of range explored in the Barry, the choir took each composer in its stride, demonstrating the relaxed flair for which it is celebrated in Ireland and beyond. The singers’ technical prowess was especially challenged – and held firm – in Stephen McNeff’s satisfyingly complex A Half Darkness, here given its British premiere.

Setting a metaphor-rich, broadly but not literally narrative text by the poet Aoife Mannix, McNeff explores the turbulent times and landscape which produced the Easter Uprising. Like all thoughtful musings on history, the piece raises more questions than it answers, with some ravishing words – “we hear the wind whipping the salt … whipping the stone” – ravishingly treated. Most striking was the sense of ongoing dialogue and the search for identity and belonging embodied by three ‘characters’; these consider events from the perspective of an old woman, a young woman and a narrator (“presumed male” according to the composer’s note). Past, present and, by implication, the future intertwine throughout this impressive choral tapestry, which threads in and out of tonality; tightly compact, yet ever-unfolding with supple forwards momentum.

Tarik O’Regan’s Scattered Rhymes has deservedly entered the choral repertoire since its premiere at Spitalfields Festival in 2006 (and recording by Hillier and the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir in 2008**). Here history is directly invoked in the form of Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame, with which O’Regan’s piece can be framed or sections interspersed in performance. CCI performed it at Gregynog without its medieval forbear, but the echo of perfect fourths, fifths and octaves rang clearly alongside pungent note clusters and frequent false relations: all this and more depicting in lovely, timeless colours the tale of romantic passion told by O’Regan’s selected Petrarch and anonymous texts.

The choir here as elsewhere gave a superb, wholly committed performance whether in tutti, solo or small groupings in between. This was poetry as music and vice versa, with sound and language given a kind of runic quality which surely speaks to the bardic traditions of Wales. As Scattered Rhymes seemed to imply, sometimes it is difficult to tell what is ancient and what is modern – but ultimately that ceases to matter. What does matter is the story: the myriad connections and points of mutual understanding across languages and cultures that speak to our common heritage beneath the difficulties of the time.

* Hopefully Welsh National Opera’s production next spring of Martin’s opera-oratorio, Le vin herbé (‘The Potion’), will also help to redress that lack here in Wales.

** For my interview with Paul Hillier, discussing O’Regan’s Acallam na Senórach: an Irish Colloquy, see https://www.walesartsreview.org/paul-hillier-in-conversation/