Craig Austin reflects on the connection between political ideologies and pop music and how that connection has changed over the years.

‘Music and art and culture are escapism, and escapism is sometimes healthy for people to get away from reality. The problem is when they stay there’ – Chuck D

In common with almost anyone who became obsessed with music at an early age I was initially attracted to the thrills, the kicks, the glamour and the wilful distraction; a captivating ragbag of unhindered possibility that has defined my taste in film, fiction, travel and trousers, for a lifetime. Admittedly, there have been periods when the love affair has waned, when commitments have been tested; perceived moments of betrayal, boredom and loss, but ultimately it is a devotion and a bond akin to Michael Corleone’s approximation of his unbreakable Cosa Nostra life code, the fatalistic recognition of knowing that ‘every time you think you’re out, they drag you back in again’. I’m in it up to my neck, you see, and there’s no going back now.

What I didn’t sign up to was an endless cavalcade of earnest rhetoric or dreary discourse, and yet as much as music has defined (and continues to define) my inspirations, my aspirations, and my ever-changing moods, it also played an early and crucially defining role in my political outlook; a turbulent and often volatile relationship that has demanded pragmatism and expediency to be demonstrated by both parties.

You can love Roxy Music (and by association, Bryan Ferry) and still be a socialist, and while it can often be a wilfully precarious tightrope act to negotiate, I’ve come to learn that it’s not an impossibility. It certainly doesn’t help that pop stars, in common with footballers, tend to be the kind of figureheads who retain a jarring predisposition to act like major league boneheads with a frequency that often defies belief.

So much so that there are very few who can claim absolute immunity from this basic tenet; the love and adoration that greeted Bowie’s return to the creative arena last year having been illustrated via the rose-tinted prism of Ziggy Stardust and the iconography of the Blitz-club Pierrot, rather than the coke-inspired Victoria station Führer salute and related fascistic ramblings that ultimately acted as a key stimulus for the nascent Rock Against Racism movement of the late 1970s.

Bowie wasn’t an actual Nazi, he was just being a bit of a dick; a creatively obsessive force who had taken his narcotic recreation to some dark and unfathomably destructive extreme. Like all junkies, he was at the mercy of his predicament, a man in a state of personal disorganisation rather than one who – for arguments sake – was business-like and ordered enough to enter into a convoluted offshore tax avoidance scheme so morally and ethically bankrupt that it spat in the collective faces of his fan-base at a time of extreme national austerity; like I said, just for argument’s sake.

The fusion of political ideologies and pop makes people uncomfortable, the received wisdom being that the two are incapable of mixing. The kind of people who will tell you this (in spite of ‘Ghost Town’, ‘What’s Going On’, ‘Paper Planes’ and ‘Common People’) tend to be the same people who will also inform you that politics and sport don’t mix; a peculiar position to adopt in light of the Sochi ‘Pussy Riot’ Olympics, the award of the 2022 World Cup to Qatar, and the cloying stench of the apartheid regime that still clings to the legacy of the Springboks like sick on the stairs. It is a line of cultural discourse that frequently masks the subliminal and often well-meaning message at its core; the tentative suggestion that political + pop = bad pop, and there are plenty of clumsy and excruciating examples of that.

Yet political pop doesn’t have to be earnest, or drab, or joyless. Moreover, it doesn’t have to be white, male, or guitar-driven. It shouldn’t be afraid to laugh (often at itself), to dance, or to celebrate. The boorish ‘disco sucks’ crowd, a regressive mind-set forever entrenched at the point where ‘punk’ and ‘hippy’ intersect, can only hope to be blessed with a spark of the immovable hedonistic rejection of conventional mores that still makes Sister Sledge’s ‘Lost In Music’ such a thing of unbridled pop joy and personal/political emancipation, a group for whom ‘responsibility / to me is a tragedy’:

We’re lost in music / Feel so alive

I quit my 9 to 5 / We’re lost in music

But dancing don’t pay no bills – believe me, I’ve checked – and yet this ruthless and seemingly interminable grip of financial and social austerity has so far failed to produce what both the Thatcher years and the decline of 70s America ultimately delivered up in righteous and joyous abundance. The absence of an inspired and mouthy assembly of artists capable of channelling the anger, the rejection and the fear is truly a first for this once-great pop nation; the songs that would once have existed to harness the defiance and inspire a generation to dance itself into the ground having seemingly been replaced by a cavernous void of entrenched defeatism and a collective sense of acquiescent ‘meh’.

The assault upon unemployment benefits by successive administrations has no doubt had its own negative creative impact, not least the opportunity that it has inadvertently offered up to the middle and moneyed classes to gate-crash, and seemingly monopolise, a party to which they had never previously been invited. Given this relatively recent but utterly fundamental shift, and the current condition of political and artistic inertia, it is easy to see how any green shoots of insubordination could swiftly be crushed by what feels like an all-pervading culture complicit in its fortification of the status quo. Careerism reigns supreme, radical opinions are frowned upon, and free-market excess within a supposedly counter-cultural framework goes resolutely unchecked.

Most recently, this flexible expediency has been stretched to an almost tragic-comic extent. When self-styled rock’n’roll renaissance man Alex Turner opts to conceal his flagrant tax avoidance behind a cowardly vow of silence and a greasy Brylcreem kiss-curl, the mute witness of the NME (a journal once so overtly political that its front covers temporarily dispensed with musicians altogether) is as complicit as it is shameful. At least when Gary Barlow sought to explain away his unapologetic avarice – ‘Take That fans aren’t interested in tax’ – he did so with the unambiguous voice of a man who seemingly had no problem whatsoever in depicting his loyal fan-base as both gullible and thick.

Turner has yet to grasp that the appropriation of a leather-clad rebel image engrained in the tradition of the 1950s blue-collar bad boy counts for nothing if the Elvis you actually succeed in emulating is the greedy, disconnected one who ultimately died on the toilet, a gluttonous self-obsessed husk. Elvis didn’t die the day he joined the army, he died the day he started exchanging pistols with his buddy Richard Nixon. But at least he paid his taxes. That Turner, via his damning silence, has seemingly got away with this disgrace – a social crime for which the likes of Barlow and U2 have been rightly vilified – says much about the artifice and stupidity of our times; the notion that to be ‘indie’ or ‘alternative’ (whatever those utterly hackneyed terms mean these days) somehow absolves the man of the public shit-storm that has nonetheless rained down upon these aforementioned pantomime turns.

It equally speaks volumes about the obedient and submissive nature of both his own audience, and an increasingly marginalised music press that fears the withdrawal of its access to a preening golden goose that, given a set of circulation figures that appear to be in abject freefall, might prove to be the difference between survival and extinction.

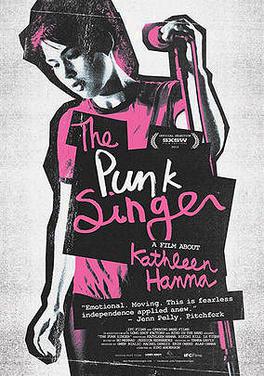

The indie scene’s habitual bullshit charade of snobbery, self-satisfaction and holier-than-thou arrogance has undoubtedly been a massive contributor to the current malaise, one that has unwittingly absorbed the prejudices and condescension of its most recent acolytes. As Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill and Le Tigre asserts, when reflecting upon her past as a nightclub stripper, in the excellent documentary film The Punk Singer: ‘If people don’t allow this contradiction to exist in musicians’ lives, the only people who are gonna make music and art are people who can afford to be pure, and that’s gonna be kids with trust funds.’ Hanna’s latest art-pop vehicle, the glorious (and defiantly danceable) The Julie Ruin is a fine representation of a band that strikes the perfect balance between discourse and dance, an electro pop assault upon both the heart and the brain:

We were called sluts from the time we were five / And teased so fucking bad that we thought we would die

We were the girls in tight jeans who always walked alone / And rode our bikes late at night to avoid going home

The Punk Singer contains an utterly riveting piece of amateur video footage of a spoken-word after-hours coffee shop performance by a teenage Hanna; a raw, furious and fleetingly unfocused display of primal political therapy. It is a rage that still exists, in Hanna, and in others. People you meet at the bus-stop, in the pub, in the supermarket; the dispossessed, the vilified, the poor; people ‘diving for dear life, when they could be diving for pearls’. Yet its ability to be channelled in a constructive, artistic, communicative way appears to have been cut off at the knees.

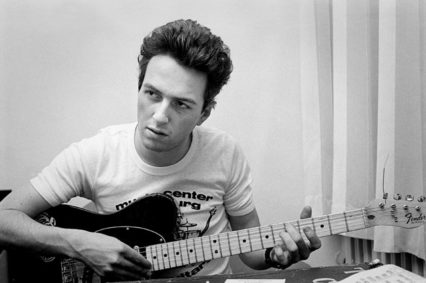

‘What have we got for inspiration?’ The Clash once asked, during a fleeting period of hot-dang good time funkiness that succeeded in culling the more bovine elements of the band’s fan-base. By all accounts the answer to that question in 2014 would appear to be nothing more than a litany of sloppy ‘gap year’ contemplation (step forward, Frank Turner) masquerading as political thought, and the latest batch of Cath Kidston village fete troubadours somehow selling out three nights at the O2.

A pop cultural canvas so utterly tainted that the term ‘libertarian’ is now presented in terms of justice, righteousness and truth, rather than the crackpot ravings of a Fox News demagogue. There’s a riot goin’ on, brothers and sisters, but its soundtrack won’t be written by these freshly inked public school bumpkins. Or to paraphrase Billy Bragg, ‘Getting tattoos is not enough in days like these’.

Whilst writing this article, I felt compelled to revisit some of the most thrilling and politically engaging songs of my lifetime. In doing so, I found myself repeatedly returning to the portentous twisted surf-guitar of ‘Soup is Good Food’, the bleakly comic high point of The Dead Kennedys back catalogue, and a staggering example of agit-prop/agit-pop execution. Though steeped in the vagaries of the band’s San Francisco birthplace, its troublingly prescient content has far outlived its Reagan-era origin; that era’s most exploitative excesses paling considerably in the face of today’s brutal social realities. It’s lyrics are twisted, scornful, and deliberately disconnected from humanity:

We know how much you’d like to die / We joke about it on our coffee breaks

But we’re paid to force you to have a nice day / In the wonderful world we made just for you

‘Poor rats’, we human rodents chuckle / At least we get a dignified cremation

And yet, at 6:00 tomorrow morning / It’s time to get up and got to work

It’s a song performed through the twisted maniacal grin of The Joker, one drenched in the eternally bleak existence of the hapless wage slave. A song from an album that on its release depicted an America built on a foundation of fear, trepidation, and abject hopelessness; one that is now increasingly, and unknowingly, soundtracking the day-to-day existence of so many people on this side of the Atlantic. Forget Cameron’s purported love of The Smiths and The Jam; this is the song that the Conservative Party should be using to open up their next party conference. To coin the phrase recently used by Ed Sheeran upon learning that the current Prime Minister was in the audience at one of his shows: ‘This one’s for you, Dave’.

On November 1st Craig Austin will chair ‘Searching for the Young Soul Rebels – Why Has Pop Given Up on Politics?’, the opening panel of Wales Arts Review’s roundtable event at Cardiff’s Millennium Centre.

He will be joined by:

Rhian E. Jones – critic and author of Clampdown: Pop-Cultural Wars on Class & Gender

Richard J. Parfitt – songwriter, former member of 60Ft Dolls, and Senior Lecturer in Music and Performing Arts, Bath Spa University

Gray Taylor – writer and member of Goldie Lookin’ Chain

original illustration by Dean Lewis

Craig Austin is a Wales Arts Review senior editor.