Steph Power attended Cardiff’s St David’s Hall for the latest performance from the WNO Orchestra including a Violin Concerto from Alban Berg.

Alexander Zemlinsky: Maeterlinck Lieder

Alban Berg: Violin Concerto

Alma Mahler: Four Songs for Middle Voice

Gustav Mahler: Adagio from the 10th Symphony

Conductor: Lothar Koenigs

Mezzo: Maria Riccarda Wesseling / Violin: David Adams / Narrator: Tamsin Greig

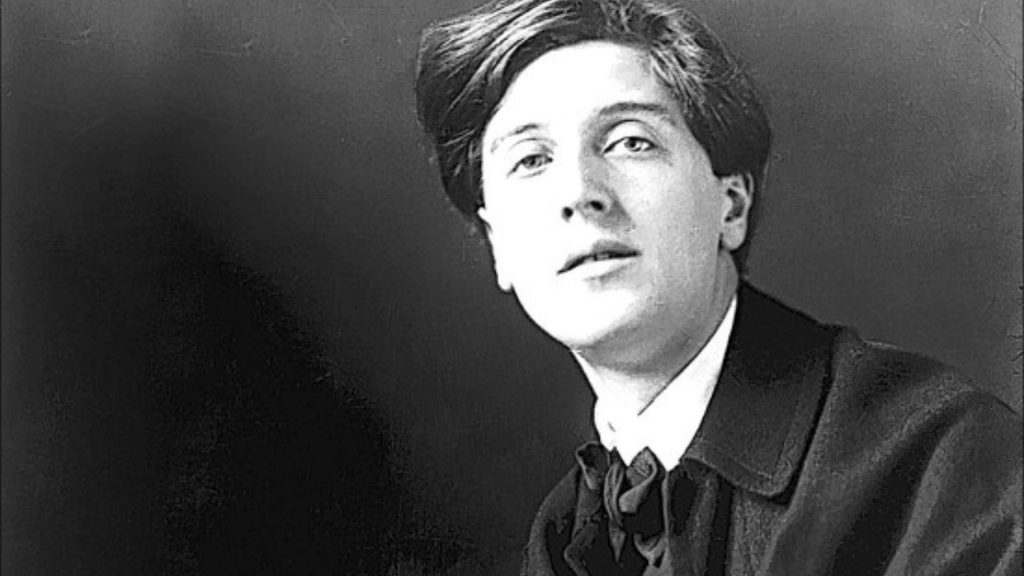

Alban Berg was reputedly shy, sensitive and private, sharing with his teacher Arnold Schoenberg a superstitious nature and an obsession with number symbolism. His music is full of hidden codes that are rarely discernible to the ear, but which, upon exploration, yield fascinating insights into a tumultuous personal and inner life beneath the smooth, bourgeois surface; often – as with the unusually direct and emotionally raw Violin Concerto heard in this Welsh National Opera concert – taking the form of complex numerological references embedded within the structure of the music. Coming ahead of a significant new WNO production of Alban Berg’s second opera Lulu (commencing tonight, 8th February), this programme was itself saturated with personal allusions both direct and indirect; exploring an intricate web of relationships revolving around the figure of its theme, the real-life femme fatale Alma Mahler née Schindler.

Mother of Manon Gropius – the young dedicatee of Berg’s Violin Concerto – and lover, wife and muse to a succession of key artists of the period, Alma was central to cultural life in fin de siècle Vienna – but never as a composer in her own right. Her first marriage, in 1902 to Gustav Mahler, was monstrously conditional upon her giving up composing, but she bowed to his request. Mahler later regretted his selfishness and, stunned by the discovery of Alma’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius in 1910 (second husband-to-be and father of Manon), set about belatedly publishing Alma’s songs which, as this rare and welcome performance of the Four Songs for Middle Voice attested, were very well crafted; perhaps the least successful being the patchy and overlong Ertelied. But together, the songs reveal a confident, mature harmonic invention and – notwithstanding some rude comments to the contrary by Alma’s erstwhile teacher and lover, Alexander Zemlinsky – a promisingly sympathetic vocal writing, performed here with sensitivity by mezzo-soprano Maria Riccarda Wesseling.

Mother of Manon Gropius – the young dedicatee of Berg’s Violin Concerto – and lover, wife and muse to a succession of key artists of the period, Alma was central to cultural life in fin de siècle Vienna – but never as a composer in her own right. Her first marriage, in 1902 to Gustav Mahler, was monstrously conditional upon her giving up composing, but she bowed to his request. Mahler later regretted his selfishness and, stunned by the discovery of Alma’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius in 1910 (second husband-to-be and father of Manon), set about belatedly publishing Alma’s songs which, as this rare and welcome performance of the Four Songs for Middle Voice attested, were very well crafted; perhaps the least successful being the patchy and overlong Ertelied. But together, the songs reveal a confident, mature harmonic invention and – notwithstanding some rude comments to the contrary by Alma’s erstwhile teacher and lover, Alexander Zemlinsky – a promisingly sympathetic vocal writing, performed here with sensitivity by mezzo-soprano Maria Riccarda Wesseling.

Alas for Alma, erotic compulsion held sway over a creative drive which was, in any case, doomed to proscription by a misogynist intellectual culture. The excerpts from her diaries of 1898-1902, interspersed as readings between pieces by the witty and adroit narrator Tamsin Greig, revealed thwarted ambition – but also fickleness and the desire to manipulate which later drove her suppression of Gustav’s incomplete 10th Symphony upon his death in 1911. The juxtaposition here of her songs with his heart-rending Adagio – both works distressingly eloquent of unrealised potential in wholly different ways – was all the more poignant for the Adagio being executed with an understated but quietly palpable despair by conductor Lothar Koenigs and orchestra.

The pieces here span over a third of a century from the two earliest of Alma’s songs (composed around 1901 and published in 1915) to the Violin Concerto; to compose which Berg put aside work on Lulu for a requiem to Manon, who died tragically in 1935 from polio aged just eighteen. In keeping with the personal focus on Alma – and regardless of Berg’s use of serial techniques in the Concerto – the works are all late flowerings of Viennese Romanticism rather than examples of the more abrasive modernism that burst forth across the arts around the turn of the century, and with which Vienna became synonymous.

It is only relatively recently that late-Romantic composers such as Zemlinsky (who, ironically perhaps, later became Schoenberg’s brother-in-law) have at last begun to attract serious consideration as denoting an important and ongoing strand in twentieth century music. The roots of Alma’s burgeoning post-Wagnerian style were clearly evident in Zemlinsky’s Maeterlinck Lieder, which are among his best works and some of the better known to date. They were performed with sincerity and conviction – but without the over-seriousness that can sometimes serve to stultify this repertoire. The orchestral colours were finely drawn and, despite Wesseling’s occasional dip below audibility, largely supported the voice in revealing a beguiling, dream-laden sound-world.

Colour and a delicate, chamber-like sonority were again to the fore in Berg’s extraordinary Violin Concerto – one of the few works to have entered the mainstream canon from the ‘Second Viennese School’ (a designation still used but increasingly unhelpful). Soloist David Adams brought poise and dignity to a work drenched in sorrow – and which, of course, turned out to be Berg’s own requiem; written at uncharacteristic speed as Berg lay ill before succumbing himself to death at just 50 years old – a premature age itself painfully reminiscent of Mahler’s own death thirty-four years before.

Alma Mahler was a close friend of the Bergs, and of Alban’s wife Helene in particular, and it was to Alma that Helene later hinted that she had known of Alban’s long-standing affair with Hannah Fuchs-Robettin. As references to Hannah continue to be decoded in the Concerto, as in Lulu and other of his pieces, the mystery surrounding aspects of Berg’s private life endures – as it does with Alma Mahler, who remains a highly ambiguous figure. However, it is most unlikely that – as recently and provocatively claimed by scholar Leon Botstein – Alma herself was the model for Berg’s central character Lulu in the opera which lay all but complete upon his death. Berg did not hide his disapproval of Alma’s open sexual licence and would no doubt have noted the irony of his widow’s later castigation for witholding the third act of Lulu from the world in a way so redolent of Alma’s suppression of Gustav’s 10th before her.

There is no doubt that Alma re-designed the image of Gustav to suit her own purpose after his death and it has taken years to unravel the sometimes blatant misrepresentation. But perhaps, ultimately, she may only be deemed ‘guilty’ of being a lone alpha female struggling for recognition in a dysfunctional society of alpha males; objectified, worshipped and reviled, as so many women continue to be who openly express their sexuality. Tonight we were gifted a glimpse into the tangled web, not only of Alma’s world, but into the complex and wounded heart of early twentieth century Vienna – the beating of which continues to resound today.