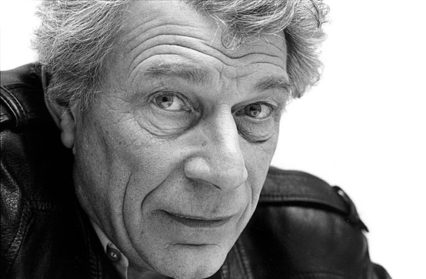

Following the death on the 2nd January of John Berger, a favourite writer and an inspirational human being, I was led to read (or re-read, if the annotations in pencil were truly in my hand, even if my memory of reading the book itself has vanished) his essay “and our faces, my heart, brief as photos“; and I was reminded, with a degree of both joy and relief, that reading and writing form a continuum, and that the one almost inevitably begets the other.

While lying in bed, reading John Berger’s strange and arresting essay, I began to drift off, as happens all too frequently when reading at night (or in the day, for that matter) and the words I read took on other shapes, that is, the eye, even though closed or half open, conjures phrases, lines, sentences; I see them, they are relayed to my brain in half sleep as though they were print on the page, but when I return my gaze to the page, no such line exists; it has been pure invention on my part, and I have taken the story off at a tangent, into a kind of dream zone, in which I rewrite the text not as image, specifically, but as words on the page which are not in fact there. I have, while drifting off, re-written the text on which my eyes were resting before I was overtaken by sleep so that it takes a new departure, unrelated to what precedes it or what the author actually wrote.

Now, this is something, as I say, that I do quite regularly when tired; it involves a shifting from what is ‘real’ – on the page – to something which I have invented, which comes from me (I imagine) or to which I am distracted or called as if by a force outside myself or the text itself.

This happened when I was reading Berger. Waking, and reading on, I find, on page 52 of his book, the following lines. Berger is in the post office collecting a post restante letter from the woman he loves, and to whom the essay appears to be addressed, as a love letter of sorts, and he says this:

A voice belongs first to a body, then to a language. The language may change but the voice stays the same. I recognise your voice before I know in what language you are speaking. In the post office you pronounced the name you had written on the envelope, yet it was not the two words which I heard, it was your voice.

And when I read that, I thought ‘Ah yes, that is exactly what happens to me!’ In other words, I saw Berger’s comment as a direct correlation – or confirmation – of the thought I had just had about superimposing my imagined words onto the words of the text. Berger is in the post office; he hears the young women clerks talking, and he superimposes the voice of his beloved onto the text of their words. It echoes, analogously, what I have just written: the text (any text) is there in front of you, but you see (or hear) something quite distinct, authored by some(one) other.

The strangeness of this world, and all its symmetries! Reading Orhan Pamuk’s autobiography of his early years in Istanbul – which also serves as a biography of the city in which he has lived all his life – he comments that:

‘. . . what is important for a painter is not a thing’s reality but its shape, and what is important for a novelist is not the course of events but its ordering, and what is important for the memoirist is not the factual accuracy of the account but its symmetry.’

Is this what guides the writer of memoir – a questing after symmetry? Or of synthesis?

To be continued . . .

This article was originally posted on Richard Gwyn’s blog, Reflections on the Mutable Universe