Frances Williams charts the narrative surrounding the statue of HM Stanley erected in Denbigh in 2011 in light of the global eruption of Black Lives Matter protests and public tearing down of statues, and explores what the ‘saving’ of the statue in 2020 reveals about more recent political histories.

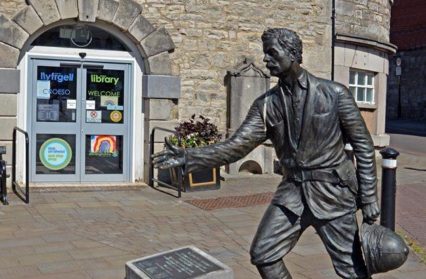

For many outside observers, the most surprising fact about the statue of the HM Stanley that stands in the North Wales town of Denbigh, is how recently it was erected. It was commissioned by the Town Council in 2010 and made by Nick Elphick in 2011. Many had demanded that it should never have been built at the outset: a petition signed by 50 prominent names was set aside by the Town Council who instead cited positive responses from local residents (a consultation involving a couple hundred respondents).

Little attention has been given, since this time, to creative re-workings of the statue which have not necessitated its removal to a museum or education context. Every year since it was first unveiled, artist Wanda Zyborska has ’re-veiled’ Stanley’s statue. This performative protest sees her cover-up what she calls this ‘toxic’ colonial figure with a life size rubber sheath. The artist has long been supported by those local residents who lament the imperialist ideology that the statue represents and who wish to continue to object to this valorisation of Stanley as a ‘local hero’.

Little attention has been given, since this time, to creative re-workings of the statue which have not necessitated its removal to a museum or education context. Every year since it was first unveiled, artist Wanda Zyborska has ’re-veiled’ Stanley’s statue. This performative protest sees her cover-up what she calls this ‘toxic’ colonial figure with a life size rubber sheath. The artist has long been supported by those local residents who lament the imperialist ideology that the statue represents and who wish to continue to object to this valorisation of Stanley as a ‘local hero’.

Following the eruption of protests globally by Black Lives Matter earlier this year, Denbigh councillors re-grouped last Wednesday to take stock of the statue’s future. A fresh petition asking for its removal was signed by over 7000 people. But in a tight vote of 6 to 5, they decided to retain the statue at its current site while a further public consultation was organised. ‘Let the people of Denbighshire decide’ was how many of them absolved themselves of the responsibility of making a more speedy decision on behalf of the townsfolk.

We can usefully compare the contested nine-year life span of the Stanley statue in Denbigh to that of Edward Colston’s in Bristol. This statue stood for a far longer period – over 100 years – in the city centre before being finally pushed over by residents in June. The slave-trader was honoured in the 1890s, a full 180 years after Colston’s death (in 1720). ’So the reasons for putting it up have more to do with their own age than the age of his own lifetime’, historian David Olusoga concludes. Applying this observation to Denbigh, why exactly was this particular figure from history celebrated in this particular place, at this particular time? The answer to this puzzle, I believe, lies in the role of certain individuals, but also the wider political and economic context established in a decade of austerity from 2010-2020. This saw not only the brutal cuts to public services, but the proffering of various justifications for these ‘unavoidable’ choices.

First amongst these individuals is a biographer of HM Stanley called Tim Jeal. He visited the town to promote his work, telling a rip-roaring tale of triumph against adversity. Flattering his local audience, Jeal suggested that it was the place that Stanley came from that proved to be the making of him. He emphasised the workhouse at nearby St Asaph, an institution which Stanley was forced to attend as the child of a poor family. Titled The impossibly difficult life of HM Stanley, this revisionist account of 2008 seeks to overturn previous characterisations of Stanley as a racist, cruel man. Stanley is presented as the victim of cruelty, though one who possessed enough agency to ‘escape’ this inauspicious beginning.

This historical genre, though arcane in many respects, sits within more contemporary topes of the ‘survival games’ which valorise individual’s will power against impossible odds. One academic proposes that ‘individual interest in self-preservation’ has been enlisted in the formation of certain contemporary political subjectivities. Harsh economic conditions are re-proposed as beneficial, rather than harmful, as they encourage acts of (masculine) assertion over those of (female) passivity. In this way, Jeal’s ripping yarn feeds directly into contemporary political discourses – such as those that pit ‘strivers’ against ‘shirkers’.

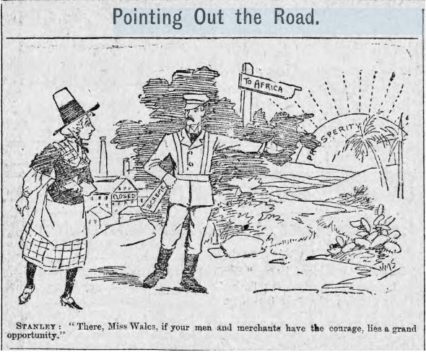

A cartoon in the Western Mail from 1893 shows Stanley pointing towards Africa where prosperity rises like the sun (Stanely urged Welsh businessmen to follow the Belgium example, another ‘small nation’ and forge its own colonies abroad). Against the backdrop of closed factories, he addresses a forlorn damsel in distress – Miss Wales herself, in full national costume. He points the way out of poverty to future prosperity. ’There Miss Wales, if your merchants and men have the courage, is an opportunity’.

Second to Jeal, is the (Plaid Cymru) Councillor, Gwyneth Kensler, a former council cabinet member who held responsibility for the Arts, Tourism and Leisure, before becoming Chair of the town council, in 2015-16. She headed-up the Commemorative group that led on the statue, using Jeal’s politicised narrative to bring together local groups, including a regeneration consultancy called Cadwyn Clywd. The £31,000 cost of the commission came from an EU grant set-up to address rural poverty. The statue was unproblematically conceived as ‘an opportunity to boost tourism and encourage growth’ (as former Labour MP for Denbighshire, Chris Ruane, suggested supportively.)

An unhealthy consensus, then, was apparent amongst local politicians of all political stripe, allowing the Stanley statue to form into a hard reality out of shared, unquestioned assumptions. This group-think ensured that opposing voices could be safely disregarded, a disposition which aligns with what author Mark Fisher calls ‘capitalist realism’ – the inability to see or take alternative routes. The statue offered Denbigh a chance to put itself ‘on the map’ through what was seen as a culture and regeneration project.

Subsequent policy frameworks in Wales further affirmed the approach taken by Jeal and Kensler. In 2013, the Welsh government linked economic growth and regeneration more tightly with their promotion of community cohesion and future wellbeing. One policy text proposed making Welsh towns ‘Vibrant and Viable Places’, while an Arts Council Wales funding pot promoted ‘Ideas, People, Places’. These funding structure – alliteratively linked – supported the idea of ‘place-making’, a concept adopted by at all tiers of government at regional, devolved and national levels alike.

Many curious disjunctures arose as a result, not least the cancelling out of the possibility of the alternate ‘difference’ that devolved government is premised upon. In a local debacle that closely echoed the one that now surrounds the Stanley statue, a proposal to draw tourists to the town of Flint failed to materialise when 5000 locals signed a petition against it. The proposal for a ‘Ring of Steel’ would have celebrated the castles of Edward I but was abandoned due to it being considered ‘insulting’. ‘This isn’t a history we want to celebrate in Wales,’ one local councillor ventured, keen to prevent defeat at the hands of the English becoming family entertainment, however lucrative. This was a step too far for those who suggest that colonialism in Wales (by the English elite) is its ‘first and final’ expression.

The Welsh Government approach to culture and ‘place-making’ closely mimicked English models (‘Creative People and Places’) and were strongly informed by Whitehall economic policy. In 2015, George Osbourne, dangled before the UK’s ‘proud cities and counties’ the prospect of becoming more than the carriers of ‘begging bowls’ to his door at number 11. He promised local power when he made his offer of regional devolution in the nearby English city of Manchester: ‘Let the devolution revolution begin!’

Welsh MPs in North Wales were keen to climb aboard Osborne’s project, set in play through the spacial imaginary of the ‘Northern Powerhouse’. Guto Bebb – a Miss North Wales of his day – grabbed the offer with enthusiasm. ‘A North Wales growth deal will revolutionise the way our towns and villages in North-Wales govern themselves’ Bebb repeated Osbourne’s cri de coeur. ‘The Northern Powerhouse, coupled with a growth deal represents our best chance to bring transformational change to North Wales’. The newly conceived geography was used in promotional campaigns which sought to sell ‘great’ Britain – as a brand on the world stage.

Spinning out into supra-national politics, the Brexit vote threw a spanner into the works in 2016. The decision to leave the EU ensured that the type of funding that paid for the Stanley statue would henceforth be withdrawn, further depleting local authority spending. No small irony, then, that the Brexit Party used the site of Stanley’s sculpture to unveil their 2019 election campaign (though mysteriously, a photograph of this event online has since disappeared.) This disappearance must be set against the ongoing visibility of the statue, whose support base has been so unsettled by recent events.

This quick tour then through some the contexts surrounding the erection of statue shows how this contested site gathers to itself energies of affirmation and retraction, making visible certain ideologies, but also pointing to their continued failure to ‘stand up’. Comparing the offer of opportunity across this time span, we can see how closely the past relates to present. Stanley is presented as an exemplar of ‘pluck’, a man capable of transcending his origins. But unlike Colston, who left gifts of benevolence to Bristol, Stanley gave nothing back to Denbigh. This renunciation of his birthplace extends to the site of his final resting place. He was denied his last wish to be buried in Westminster Cathedral on account of his bad character. Instead, his bones lie in a Surrey graveyard.

Revisionist narratives speak not just to history, but to the future, encouraging forth future imperialists. They also strike successfully at certain solidarities. ’The future favours the bold’ Osborne asserted when he insisted in 2011 that ’we are now the party of work, the only true party of labour’. Nick Elphick’s mother set up a petition to ‘save the statue’ in 2020 arguing that: ‘The work expresses HOPE for people through Stanley’s life story overcoming poverty and succeeding in life… This statue conveys a message of aspiration and possibilities to people today who might be homeless and jobless.’

A further toxic poison, then, is the way the statue continues to divide, rather than unite, across boundaries of class as well as race. As much as the statue is correctly interpreted as an emblem of white supremacy, it also directs today’s poor into what they are supposed to do with their suffering: overcome it, using superman strength. As David Wearing notes, ’Fundamentally, what’s really happening here is not a ‘culture war’, but a battle over the terms of solidarity.’ His words seem apt in Denbighshire, part of the toppled ‘red wall’ that runs across the north of Wales and England alike.

The town council may hope to ride out controversy, kicking the consultation process into the long grass of the future. But I suspect this open sore will bleed and bleed. The myth of individual opportunity will continue to be peddled and prioritised over all too real histories of colonisation, now by Johnson as much as former Tory leaders. One local resident told me she worried that ’the statue might become a magnet for the far right’, an icon around which the vandal who sprayed a swastika on the home of a BAME family in Penygroes might be proud to be associated. Art forms do indeed shade into forms of life.

Let us hope that this final possibility is one that can be rendered impossible through the actions of those who continue to point to the realities of the present in the face of wilful denials of the past. Artist and feminist, Wanda Zyborska, will return to the site of the Stanley Statue to repeat her protest this summer, though with care she insists, in a time of pandemic. She will bring with her new attention and fresh support, as she once again performs her unheralded actions of resistant critique.

Let us hope that this final possibility is one that can be rendered impossible through the actions of those who continue to point to the realities of the present in the face of wilful denials of the past. Artist and feminist, Wanda Zyborska, will return to the site of the Stanley Statue to repeat her protest this summer, though with care she insists, in a time of pandemic. She will bring with her new attention and fresh support, as she once again performs her unheralded actions of resistant critique.

You might also like…

Gary Raymond reflects on the debate around statues, and takes a look at when BBC’s Question Time virtually came to Wales this week.

Dr Frances Williams recently completed a PhD at Manchester Metropolitan University where she studied the influence of devolution on the field of practice known as ‘Arts and Health’. She is Visiting Researcher at Glyndwr University.