Kathryn Tann talks about why Women in Translation Month is the perfect opportunity to celebrate the vital work of translators and why we should access cultures beyond our own.

Women in Translation Month exists because our English-speaking island, with all its sprawling literary output, doesn’t read enough translated work – and because those we do access have been historically and overwhelmingly written by men. It exists because expanding our precious canon outwards – to unlock stories conceived of languages and cultures beyond our own – is really important. And to include the many vital voices of women writers in that expansion, well. That should go without saying, shouldn’t it?

For years, like the women whose books weren’t being translated, these vital members of the translation process weren’t being properly credited. And so, inevitably, Women in Translation Month is a celebration of the people who do the translating, too. They’re an inseparable part of the picture – and in more ways than you might think.

As a small publisher, Parthian works closely and frequently with translators of numerous languages. It has been one of our top priorities, for many years, to bring new horizons to our English-speaking readership – to try to publish ‘a carnival of voices’ – especially since being awarded an ongoing Creative Europe grant in 2017. Being from a country with its own small language (and not-so-small cultural identity), it seems natural for us to try to champion the exchange of work from other such places – and focus our efforts on books which otherwise might never have been picked up by the bigger English-speaking presses.

But often it’s the translators who we find ourselves relying upon to draw our attention to the voices most worth hearing. Julia Sherwood, who with her husband Peter has translated a number of works for Parthian, says that this element of responsibility in what she does is something she feels very keenly:

A translator is a bridge between cultures, especially in countries such as the UK where foreign languages are not taught very much […] This bridge role is particularly important in the case of lesser-known literatures, such as Slovak or Czech, the languages I mostly translate from. Most translators don’t just sit at their desk translating, they also pitch works by their favourite writers to publishers and promote the published works and authors, becoming, in effect, ambassadors for the literature they represent.

And so, while people are finally beginning to talk more about the skill and craft that goes into translating a piece of literature – crediting it rightly as an art form in itself – there is another impact being made by translators, often unseen by the reading public. Translators are still the unsung heroes of the literary world – at least from our perspective. And so, over the next year, our plan is to find new ways to spark more conversations about the processes and intricacies of translation.

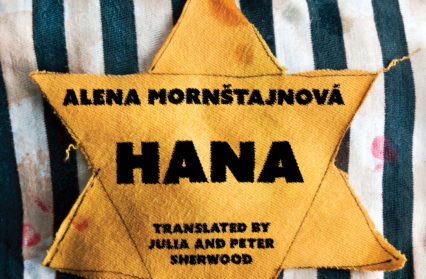

Being an ‘ambassador’ herself, Julia Sherwood has worked on – and advocated for – numerous path-making translations, including The Equestrienne and The Night Circus and Other Stories by Slovak author Uršuľa Kovalyk, as well as the soon-to-be-released novel Hana by Alena Mornštajnová (originally in Czech). We wanted to know what she had to say about the landscape of translated literature in the UK:

The Anglophone book market has traditionally been much less open to translated literature than its counterparts in the rest of the world. One reason for this is that since so many great works are published in English there is a sense that we don’t need to read imported literature. This is a view I completely disagree with. I believe passionately that works in translation enrich us by opening our horizons and by introducing us to different experiences and different, unknown or lesser-known, cultures. Now that our insularity is likely to increase due to Brexit, it is even more important to bring translated literature to readers in the UK. And as the pandemic has lately made international travel more difficult, literature in translation offers a way of transporting us to other countries, at least in our imagination.

There’s an endless feast of stories to be found and shared, some of which can be found on our very own doorstep. Translation between Welsh and English is just as important, with titles like Martha, Jack and Shanco by Caryl Lewis – and translated by Gwen Davies – widening the reach of award-winning writing, and supporting Welsh arts in both languages.

Likewise, translation can be a bringing together – a cross-pollination – of art and experience. It’s because of this that we’ve also tried to create unlikely anthologies, mixing voices from Wales with those across Europe with collections such as Zero Hours on the Boulevard – a remarkable response to the referendum produced with Literature Across Frontiers – and Home on the Move – a one-of-a-kind poetry project which resulted in rich new work. These are golden opportunities to showcase creativity from diverse origins, to see them side-by-side and to understand the ways we differ from, and also often reflect, our many neighbours.

Over the years, we’ve come to realise that it’s the small presses who are vital in making our literary geography much, much bigger. As Julia Sherwood stresses, “these kinds of publishers are more willing to take the risk to invest in writers who are not established in this country”. We’re lucky to have the financial support to be able to take those plunges towards less familiar frontiers, but we also couldn’t do it without the insight, passion and expertise of the translators who make it possible. Being that ‘bridge between cultures’, the part they play is a complex and priceless one. The very least we can do is acknowledge that.

Thank you to Julia Sherwood for her valuable insight and assistance with this article.

You can find out more about Parthian and our translated titles here.

Kathryn Tann is an editor at Parthian Books,