Nigel Jarrett casts a critical eye on All That Lies Beneath / What I Know I Cannot Say by Dai Smith, evaluating his transition from cultural historian to fiction writer.

Why does someone who has written copiously and talked eloquently and often about the history, politics and culture of Wales turn to fiction? There are two possible reasons: what has already been stated still needs to be expressed in a different form; and, fiction is simply one more form to be mastered. Let’s dismiss the latter, if only for its connotations of cleverness and hubris. So, has Dai Smith succeeded in addressing anew the matter of a certain kind of Welshness in this book, which is half novella (What I Know I Cannot Say), half short-story sequence (All That Lies Beneath)?

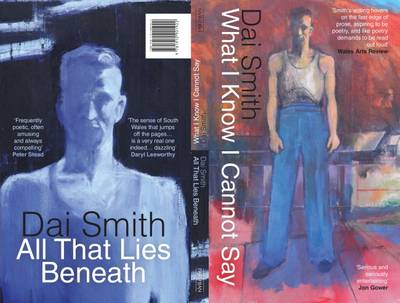

The book is certainly Welsh through and through. The author is Welsh; the publisher – Parthian – is based in West Wales; the cover illustration is derived from work by (the late) Osi Rhys Osmond, a Welsh artist by adoption and a disputatious cultural commentator to boot; and the subject-matter is nothing but Welsh. Also, the format is unusual: readers complete one half and turn the book upside down to read the second. Very outré at one time: it’s not done often but it’s not new. Is it necessary? Dai Smith is a deservedly celebrated figure – his biography of Raymond Williams is a masterpiece – so it’s surely not an exercise in smart-arse novelty incorporating an initial typo (Osmond’s name is spelled ‘Osi’ at the start of one half of the book and ‘Ozi’ at the other) and signifying nothing; the topsy-turvy format, that is. Before opening the book, the reader assumes that novella and stories are linked, though there’s no procedure indicated. The publisher describes it as ‘a tour of the South Wales valleys in the twentieth-century’, which is pretty limp sales talk that might just as well have described a valleys coach trip organised by Jones of Aberbeeg.

The difficulty for all writers attempting to depict the lives of others from their own backgrounds in former times is that they’re often no longer like them. Despite being from the same place, the same stock and of the same ilk, and retaining a life-long love and sympathy for their origins, the similarities don’t last. Often through education and the social mobility it offers, they move onwards and upwards, whatever that means. If it means physical removal, better opportunities and more congenial surroundings, the not unreasonable assumption is that what they’ve left behind is somehow deficient. It’s a crux issue for all who pontificate about their working-class antecedents from a middle-class perspective. This is not a criticism but an observable and regrettable fact, the consequence of which is to look back through a distorting lens, sometimes proverbially rose-tinted, at what is supposed to be a self-sufficient culture, not one that is merely a stage in one’s development. The working class is solid and fixed, not molten and changing in its core particulars. Isn’t it? As the coalminer-writer Lewis Jones once said, only an idiot, given a decent choice, would opt to go down the pit. But somebody had to, and then the choice didn’t seem so idiotic.

Dai Smith is clearly aware of this, and expects lessons to be learned from rupture and separation. His novella consists partly of recorded, autobiographical answers to a questionnaire for a documentary left with the seventy-year-old Dai Maddox in 1985 by his son’s estranged partner. Dai, abandoned by his mother as a two-year-old, ends up aged twenty digging coal, having been apprenticed at fourteen as a ‘collier boy’, with even earlier experience underground. But he’s no emblematic son of toil. He’s an outsider. He didn’t go on hunger marches and take part in strikes. It wouldn’t have troubled him to be a blackleg, a scab: ‘I lodged, paid the rent, mostly in the home of an older, unemployable collier. When the strikes broke out – orchestrated, more like – I saw no reason not to work, paid no subs or dues and had not a political thought in my head.’ To be fair, this was after the 1926 lockouts and before the miners had regrouped. By then Dai was out of the pit, labouring here and there, educating himself and drawing (as a child he’d been bought art materials by his adoptive uncle).

The education is important, and a familiar trope in this kind of fiction. Early on the reader is inclined to remark that Dai is a bloody good writer. He talks of the ‘rhetorical flourish’, ‘a breakdown…of some of the conventions of denial and disgrace’, and describes the goings-on in the valley bottom he could see from the smallholding where he was brought up as theatrical ‘noises off’. Soldiering and war took him to Monte Cassino, where attrition was like the Somme: ‘It could only be endured. Only endured. As if it had no end to it.’

The war is a defining point in Dai’s life and in the novella. Dai having said nothing ‘that is near to it as it happened then’, the novella then embarks on a third person, italicised account of the battle and its aftermath in which, suitably distanced as Corporal Maddox, a ‘Taff’ coalminer from South Wales with mates called Nipper and Lofty, it can be told as it was. First, he is near Turin at a vermouth distillery, and his pals are helping themselves. He then recalls how they got there, through the ‘firestorms’ and ‘hammer blows’ of the Sicilian assault. Later he comforts an injured officer, a Cambridge man, who mentions communism and its links with miners (no reaction), tells him that he (Dai) has a talent for art, and in a letter to a college friend describes Cassino’s Benedictine monastery as ‘a bridgehead…a moral and intellectual powerhouse between the values of the classical world and the ruins of the barbaric one that came after.’ Then the death of the officer followed by bathos, as a drunken Lofty drowns in a vat of alcohol. Dai Maddox: outsider, survivor and bruised witness. He returns home, goes back to the pit, takes lessons at the WEA, enters art college, and meets and marries a schoolteacher, who dies giving birth to their son.

Dai seems to need help in nailing his true identity, of expressing what he really thinks in terms of all that’s happened to him; that’s if he can bear to think about it at all. His saviour is Dai Smith himself, whose final, third-person account of how Dai coped with post-war traumas and ‘had not yet come to know how to find myself by losing myself in another’, employs descriptions here and there that even his stoic, war-weary but talented protagonist might have difficulty understanding. The scorn everyone had felt from Dai’s tongue during ‘the last strike’ – though there’s not much about the scorn or the strike – was inspired by love, not anger, we are told. ‘This was the bullion of his values, he wanted to say, not some kind of promissory political note to cash in via a Utopian treasury of ideology’. Come again? In the end not even Smith, arriving as advocate to the rescue of a man numbed by his personal history and finding no solace in society’s opportunities post-war can stop Dai opting finally for silence, the silence of his pictures. Dai’s tale told in his authentic voice and when not, as it were, textually interfered with, is vivid. The pattern of What I Know I Cannot Say is a double helix, in which there seem to be two Dais telling a story, one fictional, one factual. The former, based on the latter, is believable enough.

The story sequence, split into ‘Betrayers’ and ‘Avengers’, begins with ‘Soixante Huitards, All’, a reference to the turmoil of 1968, and features someone moving towards outsider status vis-à-vis his Welsh background. Though issuing from a family of South Wales coalminers, Bernard Jenkins is a graduate of an English university and has briefly pitched up in New York. He’s the guest on Thanksgiving day of the formidable and famous civil rights lawyer Saul Kellerman, apologist for Lyndon Johnson, self-righteous demolisher of the American Dream, and instinctive champion of the oppressed and the downtrodden. During a boozy dinner, Kellerman accuses him of betraying his father’s communist ideals for refusing to believe that a lift attendant is anything other than a shit-brained cypher, ground to inaction by the system. But Jenkins says his father, proud of his son’s achievements as an ‘exile’ would have forgiven him for what his host saw as a lapse.

Kellerman’s view of people as units to be saved by his intercession contrasts with Bernard’s, which raises their stature and renders him more capable of understanding some universal truth about people, just as Dai in the novella needed his wife’s love and understanding before he could extend his to the community that forged him and give meaning to his life. Bernard thinks the lift operator might conceivably go home to read the classics and listen to classical music. But will his Kellerman experience ever change him? Unlikely. And is Kellerman right?

‘Inter Nationals’ has Gavin the Classics student at university befriended by Jimmy, a mature student and ex-steelworker from the other side of the same Welsh town’s tracks and ‘doing’ Politics. It’s ‘Roy Of The Rovers’ stuffed with intellectual fibre, the five-a-side partnership of star footballer Jimmy and an Argentinian student being ‘physical literacy, graphic numeracy’. It’s difficult to know which grates more, the writing style’s lapse into telegraphese and the demotic, also present elsewhere, or the tortuous making of a point about wholes and parts. Jimmy, of course, flunks his studies, in case we thought he was going to be too obviously a paradigm of the working-class lad made good, albeit belatedly. Gavin is a middle-class, cag-footed gump who, after his touchline epiphany, gives up Classics for International Law. What else? The reader engages with Gavin and Jimmy for no reason other than that they are two-dimensional personifications of an idea, which is no engagement at all. Gavin, like Bernard Jenkins, may have learned a lesson, and it’s only right that he should. But will it make a difference to him? No. Will any latter-day equivalent of 1968 pass him by? Probably.

These two stories subsumed under the ‘Betrayers’ head embody the best and the second-best of the stories. They roll right on. In ‘The Bailey Report’, Bill Bailey, a top-notch TV presenter, turns up in his Bentley to film a programme about a waste dump, which is causing ructions in the valleys. Dai Smith tells but doesn’t show that Bailey had ‘no discernible political allegiance’. Donald Thomas, Bailey’s embittered, Oxford-educated producer, once had his narcissism placated and his talents employed in the broadcasting of big events that affected the lives of his viewers, but now knows he’s failed to combine the two. Bailey is recognised, by an oldie parachuted device-like into the scene, as someone who stood up for the people and gave dodgy interviewees a hard time. But Bailey’s worthy piece to camera about the dump is hollow and rehearsed. No doubt the codger and his kind were impressed in a hypnotic, televisual way.

As for vengeance, the most justifiably acrimonious character is the girl in ‘Pitfalls’, who shoots dead her violent grandfather. He’s a former miner, Great War sapper, postwar wifebeater, hard drinker, and killer of bothersome dogs. She rather improbably carts his body back to the house, dismembers it, gets rid of the bits, and makes brawn out of its boiled head, while convincing police that he’s committed suicide in grief over his dying wife. As a Grand Guignol meditation on brutality of every kind in a family battered by ‘the hammer blows of fate’, it just about prevents itself from being risible.

Ironically in a book where the author’s moral stance is suspected if not overtly stated, the most interesting story, ‘Not Anna’, concerns a woman who raises an ethical point about Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. Christine has retired and is attending an extra-mural class on 19th century love and society as depicted in the Realist novel. As a young woman, her passionate relationship with a married man resulted in a child, which she was forced to have adopted. The class is led by Derek, an Oxbridge-educated academic (we can’t get away from mentions of Oxford and Cambridge), who is otherwise rigorous in his exegeses but interested only in Anna’s motivation for giving up her child for love of Vronsky, not her reason for doing so, which is what concerns Christine. Passion and renunciation have marked Christine. As the class descends into lascivious banter over Derek’s love life, Christine departs. Smith’s conceit in having Christine die, like Anna, in the snows – accidentally, not in an act of suicide – is a conceit inverted by an alternative ending in which she survives a near-accident. Now that’s clever.

As well as the Osi-Ozi blip, there are irritating editorial typos scattered throughout, the worst – apart from lack of spacing or too much – being the absence of lipmarks before each paragraph of a split quote. Without them, the reader cannot immediately distinguish between direct and reported speech, for the closing marks only appear coterminously at the end of the last paragraph.

So, is Dai Smith the writer of fiction in this book as imposing as Smith the cultural historian? Sometimes – even though the voices of both jostle for prominence and the fiction’s route is always pre-destined. We don’t need a book about, say, a thief to moralise beneath the surface about thieving; we want to do that ourselves. And whether or not Manhattan lift operators listen to Beethoven and read Dickens when they get home is perhaps no more significant than whether anyone else does, especially the better off, who now return to different kinds of home in complicatedly changed times. For sure today they’ll all be watching crud on the telly in between breathless reports by Bill Bailey. And, anyway, what’s so culturally special about Dickens and Beethoven?

Nigel Jarrett’s latest book is Who Killed Emil Kreisler?, a story collection published by Cultured Llama

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.