‘The fact that the screen is illuminated makes you choose luminous subjects.’

So David Hockney has commented about making art on his iPad; an emerging digital arts tool which he is not alone in finding exciting. Indeed, he is just one of a growing number of artists across the world who are exploring the creative potential of fine art made on digital platforms – not just on tablets, but across an increasing range of ever more accessible digital devices from computers to notebooks, cameras to smartphones. Notwithstanding the problematic and ultimately false distinctions between ‘fine’ art and any other kind, digital art is not new; as any designer, animator, installation artist or film-maker will tell you, it’s been around for as long as digital technology has existed. What’s new is the increasing availability and sophistication of the technology, together with greater access for ever-increasing numbers of people to a truly world-wide web for the dissemination of art works online. And the proliferation of new, tactile surfaces and interactive software is encouraging new generations of artists – of all ages – to take up what might, in traditional terms, be called ‘fine’ art on digital platforms.

Carla Rapoport is an art-loving former business journalist who has spotted the rapid increase in fine art being made digitally across the globe, and who is passionate about the need to encourage and support the very best work that is emerging. In 2011, based in Wales, she founded the international Lumen Prize to that end, and it has quickly come to be recognised by many as ‘the world’s pre-eminent digital art prize’ as the Guardian culture blogger, Adam Price put it. This second year of the Prize’s running, no doubt assisted by the draw of a distinguished panel of judges (including Tessa Jackson OBE, founding Artistic Director of Artes Mundi and Ivor Davies, President of the Royal Cambrian Academy of Art), over 700 entries were received from 45 different countries – a sharp increase on the already impressive 500-plus artists who submitted work to the inaugural prize in 2012. Accessibility is key for Rapoport, who is keen to point out that any artist, no matter how well- or little-known, ‘so long as they can get online, if they’re creating [digitally], then they can communicate their work and get it judged by an internationally renowned jury panel.’

Talking to Rapoport ahead of the announcement of this year’s winner on October 8, I quizzed her about the relationship of new digital technologies to more traditional ways of making art. We started by discussing the word ‘lumen’ and she explained that,

‘Artists have been seeking light all the way back to Rubens and beyond. The use of light is key to creating almost anything you want to do in the visual arts, so I think a lot of artists are being drawn to new technology because it allows you to work with light in a new way. I think light is the key to these new technologies.’

Asked about the continued – albeit happily shrinking – resistance to digital art in some areas of the art world, Rapoport explained that digital technology is simply a new tool. In her words:

‘If you think about the creation of oil paints, they were considered quite radical at first – the idea that you could use oil paints and not grind your own colours was considered very new-fangled and wrong! Again, with the creation of printing technology, the Royal Academy refused to recognise print makers so they had to set up their own royal society – and, of course, photography “wasn’t really art”. So each innovation of new tools has been controversial.

‘Another reason the art community has found it hard to embrace digitally created art is because a lot of the people who are good at it are also geeks! We can be threatened by the technology of a computer if we don’t understand it, but we are somehow not threatened by oil paints even if we don’t understand how they’re made.

‘There is [art-making] software that you don’t need to understand in terms of how it works, but there is also art work that requires computer coding. It will be up to curators and art historians of future generations to decide which is more “worthy”. Maybe it’s the result that’s more deserving of praise! But I think people have got used to the idea that art can stretch across a whole panoply – from performance art, architecture to installations and so on.’

This year’s winner of the Lumen Prize is by an artist who has chosen to completely immerse herself in aspects of new technology. It is an emotionally moving, CG animated film by Katerina Athanasopoulou, a Greek animation artist based in London, who utilises a soundtrack by Jon Opstad that is extremely evocative, if perhaps a little too reminiscent of Arvo Pärt. That aside – and Apodemy is a film with a commissioned score, rather than a overtly ‘multimedia’ work – the pathos of its subject is beautifully understated. Athanasopoulou describes it as a ‘portrait of Athens’ conceived ‘in a time when Europe seems to be imploding’:

‘Plato likens the human soul with a cage, where knowledge is birds flying. We’re born with the cage empty and, as we grow, we collect birds and they go in the cage for future use. When we need to access knowledge we put our hand in the cage, hunt for a bird – and sometimes catch the wrong one. Ornithology uses the term Zugunruhe to describe the turbulent behavior of birds before they migrate, whether free or caged. These two images, birds inhabiting the human soul and the distress of the migrating bird became the starting points for this film, commissioned on the theme of Emigration.’

The runner-up piece also happened to involve moving images, this time in an installation realised for the Carrousel du Louvre. Here, technology itself forms the subject of the work, as the Paris-based Bonjour Lab makes fascinating interactive play with the idea of ‘data we leave in spite of ourselves, at each of our visits on the web’. Passage is the creators’ name for a ‘sensitive setup which decrypts the visual and sound imprint of those who step near it’ inside a specially reactive room:

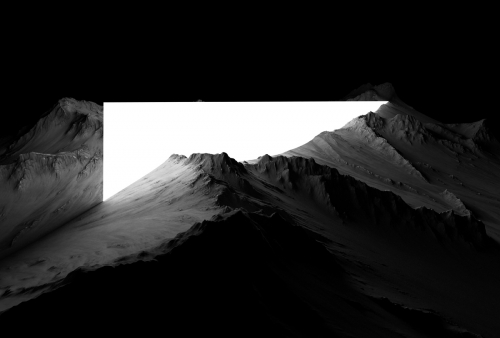

A third prize was awarded to a Swiss photographer based in London, Nicholas Feldmeyer, for his striking 2D piece After All; a monochromatic print which, for me, stood out among the short-listed entries for its clean, strong lines and quietly monumental scope. I was not surprised to hear that Feldmeyer cites archaic monuments, Taoism and the ‘sublime’ among his inspirations:

The Lumen Prize is run on a not-for-profit basis. Proceeds after costs are donated to the charity Peace Direct, which in turn subsidises entry fees in countries where it is active, such as Pakistan, Zimbabwe and Sudan. There is currently a charity auction running until November 6 and, building on the competition’s global reach online, fifty works (including all five prize winners) are touring to venues in New York City, Hong Kong and London in recognition of the continued importance of more traditional gallery viewing (last year the competition also visited Shanghai and Riga).

Returning to the subject of how the arts establishment and the public at large view the emerging digital field in general terms, I asked Rapoport whether reception of the exhibition differs from country to country. Perhaps predictably thus far, Asia seems most alive to art created through new technologies:

‘Hong Kong is particularly interesting because they just get it – there’s no barrier to digital art there. It’s a culture which is more accepting of technology so there’s even a kind of “oh this is a bit representational isn’t it? Where’s the edgier work?” – which is interesting – whereas in London they are more likely to go, “that’s strange” – no matter what it is! There is a big digital art community in the UK but I feel it’s been ghetto-ised and put off into a new media category, whereas in Asia, because it’s a newer art scene and younger, they’re much more open to this kind of work.’

Clearly, as well as in Asia, the field and understanding of digital art is rapidly increasing across the world. It is a medium which is already producing fine work – whether ‘fine’ art or otherwise – that speaks to a growing public at an international and local level. Moreover, closer to home, the Lumen Prize is yet another way in which Wales, and the city of Cardiff in particular, is emerging as a major player on the world arts and technology stages. It will be fascinating to see how the Prize, and the many artists it attracts from around the world, evolve in years to come.