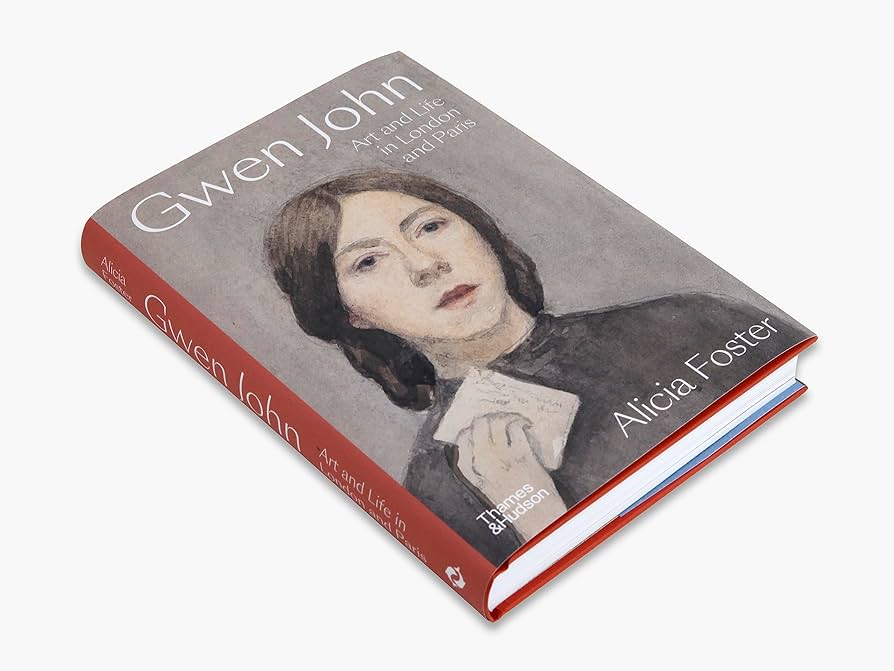

Gary Raymond looks at Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris, a new illustrated biography by Alicia Foster and asks if the age old debates about the greatness of one of Wales’s most popular artists can finally be laid to rest.

‘Nobody knows exactly why birds sing as much as they do. What is certain is that they don’t sing to deceive themselves or others. They sing to announce themselves as they are. Compared to the transparency of birdsong, our talk is opaque because we are obliged to search for the truth instead of being it.’ So says John Berger in his 1989 essay ‘A Load of Shit’. One thing Alicia Foster’s new book, Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris (Thames & Hudson, 2023) establishes in its careful accumulative portrait of the artist as a young lady is how hard Gwen John worked at being an artist. Not just the effort she put in to becoming good at painting – Foster weaves a detailed, passionate tale of the years John spent studying at the Slade, and her subsequent life in France dedicated to mastering and developing her craft; Foster’s illustrated biography does a solid job of evoking the spirit of a woman’s obsessive and authentic attention to the whole shebang. Gwen John believed great art could only come from a true artist, and she had a very distinct set of views on what a true artist was. When she was younger this might have passed for romantic affectation (friends remember her at art school being very much intent on being the artist), but this didn’t mean she was a poseur (well, not entirely); in a very real sense she walked the walk.

Foster’s framework, taking London and Paris as the palettes from which to colour John’s story, introduces us to a vibrant and alluring world. The parade of impressive figures from history may have a flavouring of Zelig, but there is no denying this is an entertaining cast of characters, and Foster never gets distracted from her central thesis. Her job is to make us believe Gwen John was in these circles because she belonged there, and this Foster does. John never comes across as out of place, be it in the company of Whistler, Rodin, Rilke, or Isadora Duncan. The cities themselves are warrens for these hot ideas and fiery personalities. They are megalopolises of contrasts, though, only when it comes to the extremity of their bohemianism. Paris was, shall we say, more laissez-faire in its attitudes to the creative communities within. London provided John with several important early influences and lifelong friends when she followed her younger brother Augustus from her hometown of Tenby to the Slade at a time when that school was the place to be for anyone with modernist inclinations. There they worshipped Whistler (there is a delightful cameo of him in the book, turning up for a tour of the institution in his wide-brimmed hat and cape, gliding through the classrooms like some condescending exotic bird) and his “arts for arts’ sake” philosophy clearly had a profound effect on the young Gwen (as it did on all the Slade students of the time). But London, it turned out, was too buttoned up, too conservative in requirements of its womenfolk, and once John had tasted Paris it was clear she wouldn’t be going back. When studying there, her friends returned to London for Christmas without her; John decided to stay alone and in the archetypal tradition of the flaneuse walked the city to the bones, alone and free (she even declined an invitation from Parisian friends for Christmas lunch, opting instead to walk alone the whole day from one end of the city to the other).

In the ambition to reclaim John from the narrative of her as an eccentric recluse, the portrait has been accepted for much of the twentieth century, Foster achieves a great deal. But as she does so, John does not become a figure in sharper focus – she remains as timorous to the eye as one of her great portraits. She is not unknowable, exactly – Foster ensures Gwen John has never been better understood – but we are always chasing after her. As a subject, John never turns and looks the reader in the eye, she is never there for us to get to know, even if occasionally we may feel her presence at the elbow, casting judgements on the characters of her past, pursing her lips and tilting her head back, disagreeing with their opinions of her.

But Foster uses everything at her disposal to get at John. Not just the fables of her behaviour (and there are many vivid examples), or the letters and postcards adding colour to the facts of her life, the whys and wherefores. Attempting to understand John through the way other artists depicted her is a highly enjoyable game and I can’t imagine anyone playing it with more skill than Foster. The pencil sketch, by Augustus, of Gwen at the easel under the tutelage of the esteemed Fred Brown while at the Slade is a marvellous example of the alchemy of Foster the art critic. “Both are standing at her easel, and Brown is making some alteration to Gwen John’s work-in-progress. Brown is something of a caricature, but Augustus captured his sister with subtlety, head tilted back as though assessing Brown’s corrections, left hand brandishing a large palette while her right hand is held tensely, as though she is willing him to stop touching her work.” One way of getting to know an artist is to look at them through the eyes of other artists.

For many, it is from the shadow of the reputation of her brother that Gwen has always been waiting to be rescued. Foster’s book is a significant contribution to this effort. There is no doubt of her significance and greatness. Augustus, who famously declared that “in fifty years I will be known as the brother of Gwen John”, can count this book as confirmation of his prescience. Indeed, Augustus himself is conspicuous in Foster’s book for his lack of a dominant role in his sister’s story. He appears frivolous and, dare we say it, something of a self-aware imposter as the genius of the siblings. He was never anything other than supportive of Gwen’s work, and that famous quote is a heartfelt example. Gwen John is a great artist. He knows it, we know it, and now it is confirmed in Foster’s book. It has been a long journey to this point.

In 1902, the Johns had a joint exhibition together comprising forty-three Augustus paintings and two of Gwen’s. Augustus’ comparative prodigious output can be put down to Gwen’s sex. Augustus had already married (Ida Nettleship, an artist who gave up her practice in order that Augustus might not be distracted by the stuff of domestic life). Gwen did not marry. Foster writes, “it is hard to imagine Gwen John giving up her hard-won independence and her art to preside over any man’s domestic arrangements – even Rodin’s – as a wife would have to, and as she had seen Ida Nettleship John do so unhappily.” She enlisted in the ruthless philosophies of artists who dedicated themselves entirely to their art. As a model (and then lover) of Rodin, probably the most famous and influential artist in the western world of the period, and a close friend of the great Czech-German poet Ranier Maria Rilke (to whom John became close when he was working as Rodin’s secretary for a time), John was further introduced to confirmation that great art only came from a true artist. Both men were slaves to this regime of total dedication.

In Paris, you could say, Gwen John found her place and she found her people. On one occasion, when her father came to visit her and criticised the way she dressed, Gwen summarily sent him packing, and for a while rejected his financial support, writing to a friend that she could not accept anything from a man who held such views. Gwen John did not come from money, not in the way other women in Paris who were carving out cultural lives for themselves did, the aristocrats and heiresses. To remain in Paris and paint she had to live in penury, relying on money from selling her work and modelling for other artists, scraping by. For several years John lived in squalor when not living in something approaching squalor in the now uber-expensive fashionable parts of Paris that were then home to rows and rows of half-derelict students digs and utterly derelict artist studios. For a time, she even took to dossing in a condemned building in Montparnasse (pre-dating the punk attitudes of the New York avant garde of the early 60s and the actual punks in the U.K. of the 1970s), but she did this both because she had no money and because she believed this was the way a true artist should live. It was not for show, not an indulgence, not a pose, but it was, at least in part, a performance that was nothing less than method for her. The resultant frugality meant that she often throughout her life, committed works to both sides of a piece of paper or even a canvas – not the easiest way to have works exhibited. The art was the thing. One anecdote Foster retells encapsulates this. At a luncheon, John met poet Jeanne Robert Foster, who recounted John “arrived ‘wildly – half dressed, her face drawn and colourless’… [she] had eaten next to nothing but drunk a little wine, and then told Foster about her life and the terrible difficulties of painting Mère Poussepin. She had a nun’s costume made for the painting only to have it ripped apart twice when it was not right. She starved herself to afford models. Spent ‘seven years of agony’ making seven paintings, hiding or destroying all of them, before finally ‘the miracle happened, the technique born of seven years travail and great love and been perfected. She was an artist.’” This focus often spilled over into self-absorption. It is seen throughout her personal relationships, and she is remembered by many who were very fond of her as selfish and difficult. Some of these memories are difficult to read they paint John as so callous. But, in the end, you can forgive anything of the painter of Mère Poussepin.

As with the technique of relating to John via analysis of artistic representations of her, Foster also dedicates a marvellous chapter to Gwen John’s library (and goes into some detail of the books that are not found in it, as well as those that are). From John’s predilection for the Russian masters, European philosophy, art theory (of course), psychoanalysis, poets, and theologians, Foster builds an intellectual waterway for John’s evolution as a thinker. Foster is layering, and the more the reader gets into the grooves, the more it becomes apparent this is the technique of a painter rather than a writer. To this extent, the book is a promenade through a gallery of impressions of Gwen John.

But I wouldn’t want to give the wrong idea. Foster does not shirk her responsibilities as an authority. She doesn’t simply throw all that diligent deep-dive research in the air and let the reader pick up the bits. In the library chapter, for instance, she deftly creates a space through the texts on the shelves (some of which open naturally to significant passages, some of which are more thumbed than others – Foster brings an immersive tactility to the process of rummaging through the books), where John’s Catholicism can organically emerge. And so, we move to the next defining chapter of Gwen John’s life.

By 1911, the intensity of her relationship with Rodin was diluting, and John was beginning to turn to religion to finalise her artistic philosophy. For the rest of her life, she would be working tirelessly to marry her work and her faith. Such an achievement would, for her, have signalled the deliverance of the whole. John began to reconcile the renaissance articulation of Christianity with the modern world, placing her own image, for instance, in the scenes of the Virgin’s story. As Foster cheekily writes, “‘…painting oneself as the mother of God is… a remarkable act of chutzpah. It fits with Gwen John’s ambitions. Now that she had embraced the Catholic faith, she would not be content to be a mere worshipper.”

Gwen John’s Catholicism, Foster convincingly argues, is what eventually elevates her from an artist of the twentieth century to whom not enough credit has been given, to one of the most important artists of the last hundred+ years. The oil painting techniques that John develops during her period of religious instruction (the 1910s, essentially) was “entirely new and original”, Foster writes. The artist who created such memorable works under the aegis of Whistler and Rodin and other masters now emerged singular and stood alone. Foster nails it when emphasising the importance of John’s work when examining her Girl Reading at the Window (1911): “Gwen John painted an everyday physical reality… as a moment of profound religious illumination, her version brings together a two-thousand-year-old story with the utterly modern, retold with no recourse to haloes and angel’s wings.”

And so, we see John moving on from Rodin in more ways than one – as in everything else she did in life, she did it with a sense of absolutism. The great work that came from her in this period, most notably the series of portraits of nuns from Meudon, were not then just inspired by God, “it was not art in the place of God” as it was for Rodin (who believed “art is God”) “but art and God being found, explored and elevated in each other. She would describe herself in a private note as ‘God’s little artist: a seer of strange beauties, a teller of harmonies. A diligent little worker.’”

If we are still debating the greatness of Gwen John, then let Alicia Foster’s diligent, but not little, and not workaday book be the final word on it.

Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris is available now from Thames & Hudson and the exhibition it accompanies is open until 8th October at the Pallant House Gallery.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.