In the third part of his fascinating introduction to the literary riches of Denbigh’s history, John Idris Jones charts the highlights of the nineteenth century.

Denbigh’s History: Nineteenth Century

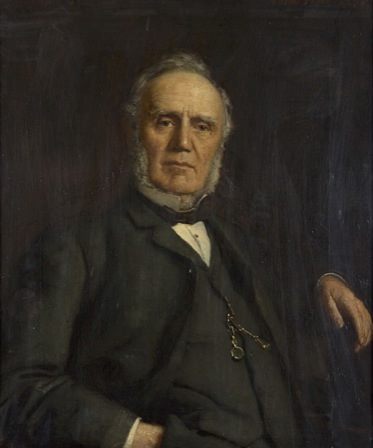

Thomas Gee (1815-1878)

Thomas Gee was born in Denbigh and at the age of fourteen moved to work in his father’s printing office: he had the advantage of being taught in the local grammar school in the afternoons. In 1837, he moved to London to improve his knowledge of printing. Back in Denbigh, he set about expanding his printing and publishing enterprises. In 1857 he started a newspaper ‘Baner Cymru’ (A Banner of Wales) and wrote, with others, the first encyclopaedia in Welsh, a huge undertaking.

He was an ardent advocate of home rule for Wales. He argued for non-denominational schooling and Church disestablishment. He was an effective public speaker with a mastery of diction: although he was ordained as a minister, he favoured the itinerant ministry.

He was one of the outstanding intellects of nineteenth century Wales; and he was a very practical man through his publishing.

When he died in 1898, he had a huge funeral. His old printing works building still exists in Denbigh.

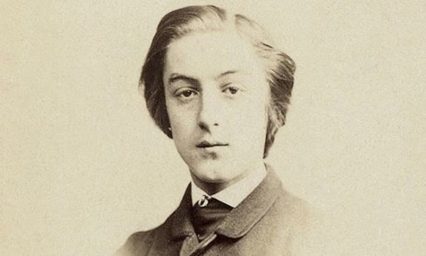

Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904)

Stanley was an outstanding figure. Few man have made such a contribution to discovery and exploration. His autobiography (edited by Dorothy Stanley, 1909) is well worth reading for its direct style and interesting selection of material. His early childhood can be described as extremely unfortunate. He was a Denbigh-born orphan, given the name Rowlands, but his male parentage is not clearly known. His mother was Elizabeth Parry (aged eighteen at his birth): his birth certificate describes him as a bastard. It is said that he spent ten years at the orphanage at St Asaph and that when he was there, his mother was admitted but the two did not recognise or acknowledge one another.

From ‘Early Memories’ in his ‘Augobiography’: “One of the first things I remember is to have been gravely told that I came from London in a band-box, and to have been assured that all babies came from the same place…later, I was informed that my mother has hastened to her parents from London to be delivered of me; and that, after recovery, she had gone back to the Metropolis, leaving me in charge of my grandfather, Moses Parry, who lived within the precincts of Denbigh Castle…my grandfather’s house, a white-washed cottage, situated at the extreme left of the Castle, with a long garden at the back, at the far end of which was a slaughterhouse where my Uncle Moses pole-axed calves, and prepared their carcasses for the market..[I was]..on my grandfather’s knees, having my fingers guided, as I trace the alphabet letters on a slate. I seem to hear, even yet, the encouraging words of the old man, ‘Thou wilt be a man yet before thy mother, my man of men.’

It was then, I believe, that I first felt what it was to be vain. I was proud to believe that, though women might be taller, stronger, and older than I, there lay a future before me that the most powerful women could never hope to win. It was then also I gathered that a child’s first duty was to make haste to be a man, in order that I might attest that highest human dignity.”

This last is an extraordinary paragraph: it seems key to the man’s ambition, will and physical fortitude. Pictures of him show a person of physical presence; handsome.

Henry took himself to the USA in 1859. In New Orleans he allegedly met a man styled Henry Hope Stanley who was a wealthy trader, and took his name. In a recent biography Tim Jeal asserts that the American Stanley was not his benefactor but that it was James Speake, a shopkeeper. Stanley joined the Confederate army and the Union army and then the US Navy in 1864. He became a record keeper aboard the USS Minnesota and started writing articles for newspapers. He became a journalist and organised a tour of the Middle east. In 1871 he visited Zanzibar with, he claimed, 192 porters. He wrote for the New York Herald. He survived a 700-mile trek through tropical forest and in November 1871 found the missing explorer Livingstone near Lake Tanganyika: his famous remark “Doctor Livingstone, I presume” may well have been made-up afterwards to enrich his written account. There is a certain doubtfulness in Stanley’s prose: “A smile lit up the features of the pale white man as he answered: ‘Yes, and I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you’.” His book was entitled, How I Found Livingstone; Travels, Adventures, and Discoveries in Central Africa’: a title which tells us something about the man.

In 1874 the New York Herald and the London Daily Telegraph financed Stanley on another expedition whose purpose was to map central African lakes and rivers and to find the source of the Nile. Stanley set out on an extensive journey of exploration and mapping, tracing the River Congo to its mouth on the Atlantic Ocean. This long and dangerous journey succeeded in mapping the rivers Lualabe and Congo and discovering the source of the Victoria Nile. Stanley described this in his book Through the Dark Continent (1878). Other African adventures followed.

Stanley married Dorothy Tennant; they adopted a child named Denzil. Stanley became an MP, serving Lambeth North from 1895 to 1900. He was knighted in 1899 as Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Bath. His grave in Purbright, Surrey is inscribed: “Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841-1904”. ‘Bula Matari’ is a name given to him by his people in Africa; it translates a ‘breaker of rocks’; a tribute to his outstanding will, physical energy and determination.

It is a story of how a boy was born with so few advantages became one of the outstanding explorers of his day; and how a boy with virtually no formal education became a writer of skill and popularity.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889)

Gerard Manley Hopkins is a name closely associated with a historical list of great English poets. In teaching circles he is often mentioned as the first ‘modern poet’ of the British-American tradition, followed by T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas and others. Like these two, he was an innovator in verse style. His method was new and unique, borrowed from Old English, with its compound nouns, and the Welsh form ‘cynghanedd’, a method which relies on line structure and repeated, regular, consonants. His was a new music.

He was born in Essex, of devout Anglican parents; the first of nine children. His father was head of an insurance firm.

Gerard converted to Catholicism: he came to the Jesuit retreat five miles to the north-east of Denbigh in 1874. This is located on the B5429, between Ruallt and Tremeirchion, under the hill Moel Maenefa. He gives an account of the setting in his Journal of 1874: “Sept 6 With Wm. Kerr, who took me up a hill behind ours (ours is Mynefyr), furze-grown and healthy hill, from which I could look round the whole country, up the valley towards Ruthin and down to the sea. The cleave in which Bodfari and Caerwys lie was close below. It was a leaden sky, braided or roped with cloud, and the earth dead colours, grave but distinct. The heights by Snowdon were hidden by the clouds …all the length of the valley the skyline of hills was flowingly written all along upon the sky…Looking all round but most in looking far up the valley I felt an instress and the charm of Wales.” The word ‘instress’ is one he used to name the essential quality and nature of a thing or place. It has significance in his style. His verse prosody is designed as a verbal mirror-image of his subject, so that the rhythm and sound of his words echo those of what he is writing about; it is onomatopoeic. His poem of 1777,’Pied Beauty’ written at Tremeirchion, is an example of this (first stanza):

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough,

And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

The fifth line is a depiction of the view down to the fields and hedges of the Vale of Clwyd.

His poem ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’, written in 1875 in Tremeirchion tells the story of a shipwreck off Germany in which 157 people died, including five Franciscan nuns. It is a long, muscular, poem, drama-like, full of the energy of the angry sea and the terror of its victims. Another of his famous poems written during his four-year residence in the Jesuit college is ‘The Windhover’: this illustrates strongly his gift of verbally re-creating the essence of his subject (the first lines of the first stanza):

I caught this morning morning’s minion, kingdom

of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,

in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing, ….

Here he takes language freely, moulding and twisting it to replicate the movement of the falcon in the air. It is an extraordinary achievement.

Few of his poems were published in his lifetime. It was his friend Robert Bridges who collected them and published them in a volume in 1918. It was then realised that Hopkins was a major poet.

After his four years at the Jesuit college at Tremeirchion, Hopkins spent the last five years of his life as classics professor at University College, Dublin.