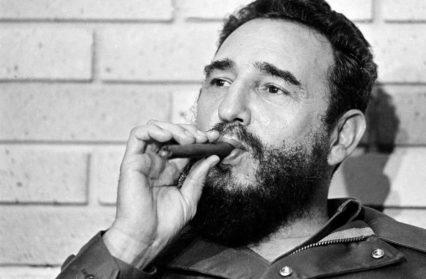

With news of the death of Fidel Castro, Cuban revolutionary, leader, and one of the most recognisable of twentieth century icons, at 90 years of age, Wales Arts Review publishes Jim Perrin‘s long travelogue on his time in Cuba from his 2002 collection, Travels with the Flea, and Other Eccentric Journeys (Neil Wilson Publishing)

Early morning at Heathrow, with a long and disjointed flight to Cuba in prospect, the thing that captures my attention is the oddity of the check-in queue. A requisite assertive neurotic demands a seat proximous to an exit. There are a very few excited, resort-bound couples, gel-haired, fat-novel-bearing. And there are two other defining categories: beautiful young black women, well-dressed and flashily bejewelled, accompanied by middle-aged and unremarkable white husbands; and lone holidaying men. My antennae quiver.

A few days later, at a table next to me in Havana’s Restaurant Hanoi sit two American journalists. One is an assured woman of a certain age, extravagantly coiffured, in a print dress, cardigan and sandals. She talks loudly, incessantly, titters when she mentions bullet holes and evidence of torture from Batista’s regime. The other stares blankly ahead, scribbles occasionally in a notebook, chops from time to time at her rice and black beans, uncomfortable as if aware of what it means to be an American in Cuba. They have as guest at their table a government official: “No, ladies,” he proclaims, “there is nothing much wrong on the streets of Havana. I assure you our police are not here in response to a crime wave. A few small problems, maybe – too many taxi drivers who take their fares in dollars on which they don’t pay their taxes – but there is nothing much else, and certainly nothing for you to worry about.”

He straightens a lapel, lifts his chin, allows an authoritative smile to travel across yellow walls, open rafters, blue woodwork. No challenge rises from the bowed heads of the other diners, no hint of a smirk across averted faces . Sound of children at play in the square outside drifts in upon us. I finish my rice and scrawny chicken, step outside and join them. A pimp standing with two women, one of them days from giving birth, catches my eye, wags a finger from one to the other in quizzical invitation. Havana, I’m rapidly finding out, is no place for this lone male tourist. The door of the church in the Plaza del Cristo is open so I enter for brief sanctuary. Inside a congregation of the halt, the sick and the old process around the Stations of the Cross in pre-Easter Mass. An affable fat priest chews on the Host and joshes his flock. The pillars that decorate either side of the nave are pre-cast concrete pipes from ragged holes in which electrical wires trail. Sacred music’s tinning out of a cheap mini-system. Christ’s blood barely streams in this firmament. I forego the sacrament, walk back down mean streets towards my hotel on Parque Centrale.

On the way, Heriberto leaps down from the bonnet of a Lada taxi to accost me. He’s a dapper little black guy in a white shirt. I lapse into defensive mode. There are at least two policemen observing our encounter, and the word is that visitors and residents must not talk:

“No taxi, no chicas, no cigars…” I rattle out at him, hand raised. He reaches to slap my open palm in a high five:

“So how about some conversation, man?” he rasps, “Where you from? What you doin’ in Havana..?”

We sit under the statue of a hero of some forgotten revolution, I breathe easily again, and send to a bar for cans of Mayabe, the malt-rich staple Cuban beer. The policemen lounge in doorways, hands in pockets, eyeing the passing girls, showing not an iota of concern for our dialogue. Which is fortunate, given the part they play in it.

“These police guys, they’re just country boys, provincials. They’re all from Santiago and they’re out of their depth, into every little racket…”

Heriberto talks on, interrogates me about attitudes towards his country, thirsts for outside knowledge, tells me he earns $12 a month as a teacher in Habana Vieja – “tough kids, good kids, streetwise!” – in a run-down, under-resourced school with classes of thirty and over. He tells of how, for all the problems brought about in his country by external agencies – the U.S.A.’s Burton-Helms legislation, its associated effect in the cancellation of Russian subsidies – for him it is the only place, and it’s booming. Look at all the new construction and tasteful renovation going on in Havana. Look at the investment in tourism here from Canada and France. He lectures me like a patriot, yet extracts a promise that I should send him British newspapers, American news magazines to leaven the revolutionary propaganda he’s fed and recognises and sees a legitimate purpose in but shrugs off amusedly every day. Heriberto provides a counterbalancing positive to a city experience that might seem too entirely predicated on hustlers of all varieties, and the glib and vitiating range of response contact with them allows. He gives me a lot to think about. I’m thinking about it when I run into Jesus in the bookshop on Obispo next morning. He wears Ray-Bans, Levi’s, a polo shirt, asks for an extempore English lesson, offers to guide me round the city, the country even, says he’s a teacher from Matazas, up in town for the Easter vacation to coax some dollars from the tourists and supplement his Government salary. I buy him a couple of Mayabes in a pavement bar with a struggling band:

“Their rhythm,” Jesus informs me, “is very contentious.”

The rhythm of Jesus’s approach is building along with the day’s heat. The beat of his story’s laid down like a slow waltz: divorce, women’s selfishness, his daughter’s need for a new pair of shoes. There’s a weariness in the presentation, an over-rehearsedness. I lure him on to state of the nation. He briefly holds a line on good things coming from the revolution: education, health care. But communism, he wails, isn’t working here. The party officials live in castles, drive round in Mercedes while the people are very poor – very, very poor. This Tocquevillean line he’s running sets me thinking of people living on the bank of the Ganges in Varanasi, owning nothing but a cooking pot, dying of TB, without money to pay for medicines even for their children. I scan round the Plaza de la Catedral, see healthy, well-dressed, well-fed Cuban people everywhere, mention it:

“Ah yes, my friend, but teachers are leaving teaching, doctors are leaving the hospitals, professors the universities. Their children go without shoes, like mine. They leave to work in bars and restaurants and hotels for tips that are three or four times their salaries. Maybe a heart-surgeon carried your bag to your room. What you see of our country’s wealth is not real. It comes back to Cuba from those who escaped to Miami – $900 million a year. American dollar is what we need.”

I don’t query the statistic, give him $5 instead and slip away. He’s tired of working the dollar-face, exasperated at the sense that his chisel’s hitting a resistant seam. I’ve no idea whether his story was true or not. All I know is that he’s told it before too many times in a town where everyone has something to sell, whether it be cigars, roses, paper twists of peanuts, sex or their own private sorrow. So many stories, so many demands. Later, I drift up the Prado – the tree-lined, marble-terraced boulevard that runs from Parque Central down to the Malecon and the sea. Two etiolated ducks quack from the balconied, decaying elegance of a neo-classical slum. The house next door has fallen down. Across the next junction an immaculate Chevrolet Bel-Air draws up outside the Palace Matrimonial and a couple emerge, the bride swathed in yards of white tulle, to sweep past another couple – she sixteen and pregnant in a faded blue dress – who wait their turn at the foot of the steps. It’s ostentation and exigence in one of their habitual Havana conjunctions. The visual impact of this city, ranging from architectural elegance to the most abject decay, is enthralling, overwhelming. But as a tourist you range among it as one of the hunted, as prey, able to glimpse it only in moments of respite, seldom afforded even the slightest view into the lives of the ordinary people who inhabit and for the most part thrive here – new hospitals, immaculately uniformed schoolchildren, impressively high statistics of literacy and continuing education comprise one aspect of Cuba’s social reality.

I head on down to Parque Centrale, sit outside the Hotel Inglaterra. Crocodiles of small schoolchildren in bright red skirts and short pants with crossover braces wind by. Around the bulbous silver trunks of the palm trees opposite, under the admonitory white marble finger of Jose Marti, watched by a woman police officer notebook in hand, a constant hundred or so men swarm, cacophonous, gesticulatory, striking mighty unfocused blows, names drifting out of their discourse and into my recognition: Mark Maguire, Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio. Two of them detach, walk across the street, talk to me over the barrier. I shake Julio’s hand. He winces. He has an abscess between his fingers, needs a couple of dollars for folk medicine. Rafael is just poor and hungry. His brother’s in Miami, but never writes – or at least, it never gets here. How could it? Then Magda arrives, takes a seat. She waves the men away. Her assurance is breathtaking. She gestures to her face, asks if I think her pretty. She is. She slily hoists up her skirt. I look away, sigh, hold up my hand, tap my ring. She smiles, nods, tells me she’s married too but no matter. Tonight we shall go dancing at the Cafe de Paris and she’ll arrange it so that afterwards I can stay at her place. I have just met this woman, have given her no encouragement. These are the first words we are exchanging. My notion that she’s a prostitute seems mistaken. She tells me she’s a secretary. She’s just sexually confident, straightforward about what she wants. But it comes across as hustling. And it compounds. The significance of those lone men at Heathrow begins to dawn. I buy Magda coffee. She tells me she’s hungry, points to a display of cakes. I give her money for them. She smiles at me engagingly as she puts the change unbidden into her handbag. I turn the conversation to economics:

“Ah, Cuba – mucha problemes!” She laughs gaily, as though whatever those problems were, they do not affect her. I pay the bill, make a polite farewell, break for the safety of my hotel to regain faith and enjoy some privacy. Magda follows. As I’m mounting the stairs I glimpse her by reception. Money passes across. In my room, the phone’s ringing. I shut the door again, take the elevator to the rooftop bar, look over the skyline of this strangest, most compulsive, in some ways most repellent of cities.

What can you say about it when your experience as an ordinary tourist here is so pressured, the pleadings of the people who fasten upon you often so apparently desperate? Surely it cannot all be thus, and what you’re experiencing is a kind of legislated divorce, born of necessity, from the real population? The cultural texture is vibrant – “music in the cafes at night and revolution in the air”. The colonial architecture’s an inexhaustible fascination. It rears up against a gunmetal sea and a hazed sky, imposes on that plain wash a texture so weird that the tribes of heavenly appearance who throng its streets might have dowsed hell in sunshine to create it. The operative principle is entropy. Everything here is in decay. Shadow it and you might think it was the blackened, molar stumps of Dresden after the firestorm. But there is no shadow here, and the people are gay. Plaques of stucco peel from crumbling brick, sewage weeps into the streets, pneumatic drills sound from every alley as construction imposes its thin new veneer, washing flutters in squalid stairways, wrought iron and ornate plaster rust and crack, Spanish, ecclesiastical-baroque and Soviet-functional styles jumble and the streetlife mills joyfully amongst it. I descend again. I want to see the Musee de la Revolucion, because for me all that ideology is what Cuba is about, is what has brought me here.

It’s in the former Presidential Palace. On its marble staircase, above impassive busts of Marti, Juarez, Bolivar, Lincoln, bullet-holes pock the wall, date from the attempt by students to assassinate Batista in 1957. Elsewhere, slogans dominate: “Memories, rejoicing, reflection, courage to continue the work! Let’s travel together on the same path – the path of hope, the one that will definitively lead us to victory!” Three young Cubans in dreads and combat fatigues wander among them, brimming with gestural elation. I study old photographs: Che Guevara in all his long-lashed beauty, dead, a uniformed man inspecting his hair; a group of six revolutionaries from 1958, one of them bespectacled, wisp-bearded, reading a dog-eared volume of Jose Marti, another a young woman with the blank gaze of loss. In one room a video’s playing of Castro delivering the address at the opening of the Santa Clara memorial to Che. The camera lingers on the size of the crowds, on the emphatic, intimate way of speaking. Fidel’s in his drabs, grown old, grey in his beard, but the stature impressive, features hewn from granite, flash of the eye still dangerously thrilling. Heads of police and soldiers who pass through the room swivel – particularly those of the women. I ‘m briefly revisited by that visceral appeal there once was for those of the political left in Britain at mention of Cuba, realise articles of faith are still at play here: Fidel as God the Father, Che the Son, Revolution the Holy Ghost. But it’s run short of funds. The dollar’s a more potent object of worship now. It buys bread.

Back in Parque Centrale, Caribbean clouds are building. The statue of Marti, so dazzling-white in the morning, has faded to a dull grey. Raindrops blotch the pavements. Tourists hurry in under awnings, dimly conscious maybe that systems preaching principle and justice can only be undermined by the influx of manifest inequity. Water streams down through thick foliage of laurels above the baseball devotees, quenching their ardour, stilling all the frustration and pride of those extravagant strokes. I watch them disperse, and wonder about the potent, distressing country they inhabit. Its revolutionary fervour seems in its official expression to have dissipated into sloganeering. On the streets, those you are likely as a visitor to meet are both exponents and victims of a grasping material envy. Maybe the ideology of revolutions always peters out thus? It’s over thirty years since Che left Cuba, to meet his death at the designings of the C.I.A. His image is everywhere, on every tee-shirt and street corner countrywide. But his example’s gone underground in this brave, vulnerable, resourceful little nation where Uncle Sam’s subversive greenback’s everyone’s indiscreet object of desire, poised for the final counter-revolutionary coup. Havana, ultimately, leaves me harassed and depressed. I decide to head up-country to seek out some remnant of Cuba’s uncorrupted elsewhere.

But to escape from Havana by road is a version of tasks set in nightmare. There are no signs or apparent thoroughfares. Geographical boundaries conspire to whirl you back into the innermost circle of urban hell. The only consolation is that Cuban drivers for the most part proceed at funereal pace (of necessity, since they drive immediate-post-war Detroit dinosaurs designed to run on seven litres of V8 and now mostly converted to 1200cc’s of Lada power). If chance so wills, you pass the Nassau cruise ships towering over old Havana’s tenement blocks, craze your way through divers junctions and Caribbean versions of council estates and perhaps eventually emerge on to Autopista One heading east. You know you’ve arrived by the crowds, and by the policeman who keeps them in check and makes sure they wait their turn. They’re hitchhikers. If your car has a “Particular Cuba” number plate he’ll flag you down and fill it up – with people. If it has a “Turismo” number plate you don’t get coercion. You get moral pressure. Go past without stopping and the fists would be waving in the rear-view mirror. This is a communist country. The prevailing ideology says you share. So wherever you go, you have company. It’s useful. Those roads – three or four lanes of white concrete in each direction shimmering across the endless plains – get lonely. The dark abbreviated crosses, fringed with a dirty white, of the turkey vultures circling overhead give you a sense that they’re dangerous, too. There was the Buick Six with flapping wings reversing at speed down the fast lane, for example. The two men in it had decided to return for a particularly attractive hitchhiker a kilometre or so back. She was striking, but then, Cuban women so often are. I was looking at her as well, in the mirror. My newly-acquired passenger brought my attention back to the road. He grabbed the wheel. Just in time. We laughed. He was going to Santa Clara and so was I – 200 miles of mid-day heat in something called a Daewoo.

You go to Santa Clara out of revolutionary respect. This is Ciudad Che – Che City – home to El Guerilla Heroica’s remains, site of the decisive battle at which the revolution was won, and the place where Batista’s forces surrendered to Guevara on 1 January, 1959. It’s a dusty little hot town. I stay in the Hotel Santa Clara Libre. It’s a green and pokey concrete high-rise pitted with bullet holes from the last days of 1958 and the last stand of Batista’s forces. From its rooftop bar you look down, as they must have done, on Parque Vidal. The bandstand’s empty. A woman nurses a child and talks to a dreadlocked black youth under trees that shed orange and pink blossoms upon them. Marble pulses with heat. Afternoon bystanders and flower-sellers seek the colonnades of the Teatro La Caridad, where Caruso performed, and the Palacio Provincial. A flock of white doves gleams momentarily white against the tawny aridity and hazy distances of the plains. The hotel’s water and electricity are off. In the restaurant Ramon, the old waiter, offers a rare take on the essential decency of the Cuban revolution: “I never went to school. Before the revolution there were none for the poor people. But now, see, I can read and write.”

Ramon inspires me to visit the two significant memorials in Santa Clara. A rickshaw driver races me along alleys to the first, half a mile east of the town. It’s called Monumento a la Toma del Tren Blindado. A little river winds beneath laurel trees, the railway cuts in dye-straight from the plain. Between them are five de-railed wagons, a bulldozer on a plinth, and one of those assertive concrete memorials, all splayed fins and abstraction. The bulldozer cut the line. The train had 22 wagons, 408 soldiers, arms to reinforce the garrison. Che captured it with 18 men and a few rifles and that was the end for Batista’s rule. A guard lazed in the shade and watched me in and out of the wagons. There are more slogans than guns in them now.

The other monument’s west of town and it’s magnificent. You see it from miles away, a huge statue atop a column, the ultimate expression of the Cuban cult of Che. He’s urgent, forward-leaning, shaggy. This is Christ Militant with his hand on a gun and a grenade in his belt, idealism and a secular sanctity gleaming from a corona of beard and black curls. In a vault beneath is an eternal flame, and bas-reliefs of all the young altruists who died with Che in Bolivia: “This”, my young Cuban guide tells me, “is Tania!” She glows with pride at the female revolutionary example, and asks me for a dollar. I take the concreted road out of Santa Clara through the Sierra Escambray. Ken Livingstone wrote recently that it matches anything in the Himalayas. It doesn’t. It threads through soft, wooded hills of oolite, valleys of rich red soil. The surface is dire, the surrounding jungle benign. You pitch out of the hills into Trinidad.

Most World Heritage Sites become victims of their own popularity. Trinidad hasn’t quite suffered that fate yet. Its townscape bespeaks the colonial wealth of 200 years ago, its physical fabric surviving little-changed. It’s wrought-ironed, red-tiled, pastel-painted, marble-trimmed, cobble-alleywayed, baroque-towered, and it looks down on to the Caribbean beaches a few miles away. Tourism’s come to squat here among the grand and empty habitations on the hill from which the life of the town has drained away. Slowly the flaggings and museumisings and signpostings intrude, the souvenir-street-market of fine lace and crochet, cruder wooden carving, spreads along from the Plaza Mayor. Everyone has a cigar to sell, every cocktail’s the most delicious, every palador (the restaurants in private houses which proliferate throughout Cuba) the best at which to eat. In the shade of the Taberna Canchachara the sightseers in for the day from Playa Ancon cosset their lunchtime bottles of Cerveza Nacionale and break into spontaneous applause as the solo drummer concludes each masterclass with a resounding “cha-cha-cha”. But at five o’clock, a change: the coaches leave, people come out, bands play on the streets, in front of the houses clicking domino-schools gather, a lone saxophonist riffs and trills on his doorstep, doors open to afford glimpses into cool courtyards, the sun bronzes down into the Bay of Mexico, real dark floods through the streets. I eat in Carmen and Marun’s palador. Myself and two Frenchwomen sit at an oilcloth-covered table whilst Carmen shuffles pots and frying pans on a small gas stove and serves up exotic fried vegetables, battered mysteries from the sea, on mismatched 1950’s jazz-patterned crockery. Marun punctuates the meal with mangoes from a garden tree, flirts with the Frenchwomen. The woman who brought me here asks if I will need a chica – a woman, and by implication a sexually available one – after the meal. I decline. Marun tells her I am greedy, and want the Frenchwomen. They scowl a little wearily at him and harangue Cuban morals. Carmen takes my hand and firmly shows Marun the ring I’m wearing. He’s unabashed, fondles one of the Frenchwomen, gets a sharp elbow in his ribs from her and a kick on the ankle from his wife, retreats into the night laughing at the ways of women. I pay eight dollars for lobster, beer, salad, floor-show, then wend back to my hotel. Next morning over leisurely breakfasts two enterprising widows from Esher in prints of muted lime and turquoise discuss quality of coffee and their history of hairdressers before sallying forth into town. I leave for Camaguey.

Cuba’s third-largest city is famous for its pots. They’re huge, made of terracotta, called tinajones and were meant to hold water, for this city of the plains is a dry furnace of a place. Nowadays they lounge about the colonial squares in signal fashion under the more urgent graffiti of the revolution: “Morir por la Patria es vivir!” “Confianza en el Futuro!” – this latter illustrated by a cow, an orange as big as the pots, a factory, a tractor, a guitar. The mottoes are no more grating than Harvard Business School mission statements. They just come in bigger, brighter letters. Camaguey itself is an indescribable architectural jumble strewn around courtyards of shadowy silence that hide behind shuttered windows, studded doors. Its main attraction, the Plaza of San Juan de Dios, is eighteenth-century colonial at its most simply picturesque, all pastels and colonnades and very quiet, for this is not a tourist town.

Nor is Bayamo, to which I drive on next day, and which impresses me more favourably perhaps than anywhere else I see in Cuba. It’s centre’s focused, elegant, local, river-bounded. The church of Santisimo Salvador on the Plaza del Himno Nacional has huge presence, dates from the Sixteenth Century, is being restored. The custodian introduces me to a guide and refuses my reflex-action proffered dollars; the guide himself at the end of the tour only wants a limonado chico from a street stall. The pressure lifts. In balance, colour, harmony, the Plaza and the adjoining Parque Cespedes come to seem like an expression of the town’s spirit instead of the more normal Cuban version of some ruin the Twentieth Century happens to inhabit. Inside the church an apsal frieze – martial, vigorous and quite unspiritual – reminds that this is the place where the Cuban National Anthem was first sung:

“Al combate corred, Bayameses…

No temais una muerta gloriosa,

Que morir por la Patria es vivir…”

(Hasten to battle, men of Bayamo,/Do not fear a glorious death/For to die for the fatherland is to live…”)

The town’s peaceful these days. Mimosa petals drift across plaza and parque. In the cool of evening a stout, elderly black woman sweeps them into mounds with a besom. Girls tilt languorously across the carriers of bicycles, arms draped round the riders’ waists. On the terrace of the Hotel Royalton I talk in French with a young black man, Henriques. He’s a singer in a cafe., bestows on a policeman who’s observing us a hard, rebellious stare:

“He’s from Santiago”, he tells me, “we take no notice of them here.”

Our conversation’s drowned out by the arrival of Bud, a large, slack, loud American. I express surprise at meeting him in Cuba.

“Listen, my friend, there’s no – read my lips – NO prejudice against Americans in Cuba. Ain’t that right, Chico?”

The little man at his side nods, weight of a large arm round his shoulder.

“You limeys think the Cuban people all worship Che. You’re wrong! They worship the mighty American greenback and I got plenty of those for what I want.”

He gives me a significant wink and eases himself behind a table next to a pretty young black man. Henriques, who’s been following this with puzzlement, asks me if the American’s here for the chicas ? I tell him I think not, that his preference seems to be for boys. Henriques cranes round in open-mouthed astonishment, looks at me and laughs. I end up in Santiago next day. In the Taberna Dolores, Emilio and his sister Emilia seize on me, suggest a music club. Lured by her chiselled ebony beauty I say maybe, so long as I end up in my own bed, and then I drift downtown. The cathedral’s an impeccable magnolia picked out in white, rests on a stained commercial plinth. The bay glitters down shabby, plunging streets, hills against the sunset beyond. Kids play baseball with scaffolding tubes and bottletops on the Padre Pico steps where Castro blazed off the opening rounds of his first offensive against Batista. A group of men in dirty vests perched all over a 1940’s DeSoto hand the circulating rum-bottle down to me outside the municipal market where the plantains are piled high. At a snack bar on the wharves a beggar comes over, very old, very ill. I give him a dollar and the sandwich I’ve not begun.

“Viva Cuba!” he breathes.

Yes, but for how long..?