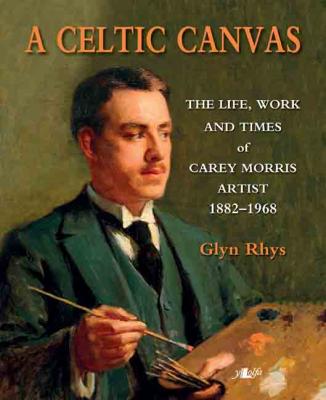

Y Lolfa 2013, 112pp

Glyn Rhys’ book on Carey Morris is a slim book of great elegance. Y Lolfa is its own printer and binder and has done its subject proud. Morris’ work is all privately held with the exception of one portrait in Carmarthenshire’s County Museum and four in the National Library. For the landscapes and less formal portraiture the reader is dependent on the quality of Y Lolfa’s reproduction. The book has a format of eight by six inches with many pictures represented full-page. Those like ‘Daf’ir Felin as a Fisherman’ and ‘Ann’ are beautifully rendered with great subtlety of hue in the colouring.

Glyn Rhys’ book on Carey Morris is a slim book of great elegance. Y Lolfa is its own printer and binder and has done its subject proud. Morris’ work is all privately held with the exception of one portrait in Carmarthenshire’s County Museum and four in the National Library. For the landscapes and less formal portraiture the reader is dependent on the quality of Y Lolfa’s reproduction. The book has a format of eight by six inches with many pictures represented full-page. Those like ‘Daf’ir Felin as a Fisherman’ and ‘Ann’ are beautifully rendered with great subtlety of hue in the colouring.

Glyn Rhys is not a professional writer but a doctor, most latterly Consultant Community Physician for Ceredigion. But he writes from long acquaintanceship with his subject. He knows from first-hand how war injury rendered Morris ‘a permanent semi-invalid’ and that his career as an artist was impeded by the limits placed on his time and concentration. Rhys gives thanks and acknowledgements to many, not least to the Carmarthenshire Antiquarian Society for financial support. Those mentioned include renowned names from the art world like William Wilkins and Peter Lord but the publication is also a family affair. Much of the work has been photographed by daughter Ffion and the scanning and editing work is all hers.

Carey Morris’ life is straightforward. He is born in 1882 in the Llandeilo family home opposite London House. The family business is painting and decorating; a photograph shows father Benjamin, with waistcoat and fob watch, leaning with pet dog against the gate of a later home, Prospect House, also in Llandeilo. The memories of childhood include observing elder brother Robert at art class. At Llandeilo’s National Church School an irascible teacher has a habit of bringing a wood-framed writing slate down on the head of a deserving pupil. On occasion the degree of force is sufficient to smash the slate.

Pedagogic violence in the form of caning extends to the boy Carey for drawing life figures in art class in place of the mundane exercises ordered. Nonetheless the artist’s testimony is ‘my childhood was full of fun and happiness.’ There is fishing to be done in the Tywi and father is persuaded to spend ten shillings on a pin-hole camera. This first making of images has a profound effect. ‘This developed into a stronger urge to do something on a higher artistic plane and paint from life.’

A reading of Gray’s Anatomy is followed by books on Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Hals and Velazquez. By his late teens Morris is setting his alarm clock for the first light and drawing with only short breaks until eleven at night by candlelight. ‘Art is a hard taskmaster and success can only be attained’, are his words, ‘by hard work and long hours.’ Relaxation is a cello.

When the period of self-teaching reaches its limit Morris opts for the Newlyn School of Art over London and writes to Stanhope Forbes. Newlyn is then at the peak of its fishing activity and its beach and streets are thick with the smell, scales and innards of pilchard and mackerel. Morris’ artistic credo is taken from the realism of Courbet. The work from this time includes 1905’s ‘the Goose Pond at Land’s End’, illuminated by the quality of light to be found at Britain’s extremities. The first portrait to gain acceptance at the Royal Academy is that of Walter Langley in 1911. An earlier commission has been Sir Lewis Morris of Llangunnor, influential in the funding and founding of Aberystwyth’s University College. The small portrait, twenty by twenty-four inches, conveys a melancholic sadness. Lord Glantawe is necessarily painted in sheathes of red and ermine but the expression on the face that surmounts all the finery is far-away in thought.

Glyn Rhys identifies Morris’ significance as the only artist to complete large-scale work on domestic scenes of then Welsh rural life. He instances the large canvas ‘Welsh Weavers’. The book covers the years of war service with lengthy quotations from Morris himself. ‘It was hell let loose’ reads one entry. The art from the time includes a haunting sketch of the trenches executed with bits of charcoal, most of his tubes of paint having been lost in a bombardment. Illness from the inhalation of chlorine gas sends him for a year into various hospitals and spares him from the offensive of July 1917. Post-war he enrols at the Slade for refresher courses.

1922 is a milestone with his appointment as first Honorary Director of Arts and Crafts for the National Eisteddfod. Under his guidance the starry list of exhibitors includes Brangwyn, Lavery, Clausen, Monet even. He persuades Winifred Coombe Tennant and the Davies sisters to loan pictures from their collections. In the view of the author, Morris’ leaving of the role at the Eisteddfod is ‘followed by a rapid decline in its status and appeal … the status of competitions descended to the parochial level of a village show.’

Morris is unimpressed by educational officialdom’s policies toward art teaching. Rhys cites an associate, Isaac Williams: ‘any educational body that does not give efficient instruction in aesthetics is dead to the meaning of Art.’ Rhys provocatively adds, ‘he deplored the fact that we accept bad art and are degraded by it.’

Social life continues with his proficiency on cello continuing. The presence of a studio in Chelsea’s Cheyne Walk ensures a stream of portrait commissions until he returns to Llandeilo in 1936. Paintings of the town ensue. Rhys makes a detour of some length for the design of a flag for Llandeilo unfurled by the seventh Lord Dynevor in 1928. The exhibiting continues, the work including illustrations for the translations into Welsh of Bunyan and Hans Christian Andersen. The death in 1968 follows the briefest of illness, Morris at his easel just four days earlier.

The aesthetics are described succinctly by Kyffin Williams. The shadow of Stanhope Forbes runs long, ‘the main beneficial influence on his work.’ In the smaller work such as ‘Dafi’r Felin’ Williams sees ‘spontaneous fluidity … Spontaneity is, I believe a characteristic in Welsh painting.’ Rhys gives an entire page as an appendix to an analysis of ‘Welsh Weavers’. In the painting of portraiture he writes of its making over time. Morris ‘believed that empathy between artist and sitter … resulted in a picture containing many moods.’ He notes the strength of the hands that Morris gave to ‘Merfyn Williams’, a mason by trade. Rhys admires justifiably a small charcoal of Gwynfor Evans.

A Celtic Canvas is illustrated with twenty photographs and seventy-one examples of the work. Asides on Jackson Pollock and Tillanook Cheddar – a commercially successful Jack Russell – are not strictly necessary. The best of the work speaks for itself. ‘Une Vieille Femme’, ‘The Connoisseur’, ‘Garden in Highgate’ are of the Newlyn school but beyond it. The shading of the drawing ‘A Housemaid’ is high accomplishment and ‘The Chateau at Boesinghe’ and ‘The Billet – Flanders 1917’ are filled with emotional clarity in their observation.