Yvonne Murphy asks what kind of society do we want, in a reflection on the Arts Council of Wales’ investment review announcement that paves the way for the future of the Welsh cultural industries.

An urban myth was doing the rounds nearly 10 years ago on social media. It went something like this: “When Winston Churchill was asked to cut arts funding in favour of the war effort, he simply replied, ‘then what are we fighting for?’ ” There is no known record of Churchill actually saying this. He did say: “The arts are essential to any complete national life. The State owes it to itself to sustain and encourage them.”

A Second World War provided a horrific impetus for us to imagine the society we wanted post war leading to the creation of the NHS and the Arts Council. Over seventy years later we must once again seriously consider what kind of society we want and think about not why but how the creative sector and creatives and artists are part of that reimagining. We need some fresh radical thinking and to enable that we must ensure creatives and artists are ‘be at the table’ and embed them in our in decision making processes.

In the recent Arts Council of Wales investment review 139 organisation across Wales, and across all art forms, applied for the holy grail of multi-year funding. 81 organisations were successful, 23 of which were awarded core funding for the first time. Of the 58 who didn’t make the grade a handful were previously core funded, the largest of those being National Theatre of Wales. This process follows hot on the heels of Arts Council of England’s investment review which also oversaw large scale organisations losing their funding and was also followed by much analysis and challenge of the process and decision-making. The recurring theme is that arts councils are making tough decisions with too small a pot of gold and whatever way they slice the pie there’s not going to be enough to go around.

There are so many questions which need answers. Questions concerning the process of an investment review where micro organisations, led by one or two freelance creatives without core funding, are asked to go through the same process and are judged by the same standards as large scale core funded and well-resourced organisations with salaried members of staff. Questions around why a review of English language theatre in Wales, or theatre as a whole, was not conducted prior to the investment review and why strategies for all art forms were not already in place before these sector changing decisions were made. (All companies who applied had to have their house in order with all policies and business plans and strategies in place which begs the question of why Arts Council of Wales did not also have to do the same?).

Questions about how the separation of art forms within live performance impacts both artists and audiences and what the role of any national arts organisation is within the wider ecology and how an investment review effects the whole ecology of the sector including freelancers. Then there also are ongoing questions around transparency and accountability and boards and leadership and pay and a salaried versus a freelance workforce. For example why is there no public pay scale for the sector? Why do some leaders earn 70-90k a year whilst many in the sector struggle to make ends meet and push above the mid 20K range? Why were micro organisations applying for the first time told that their ask, and proposed salaries above 40k for the leaders of those organisations, were considered too high when no official pay scale exists. And does a leader of a large scale organisation really deserve a higher salary than a micro organisation (or a freelancer) when it could be argued that the workload and responsibility of everything from strategy to operations and finance, fundraising and marketing and the writing of every single piece of copy and policy falls onto the shoulder of one or possibly two individuals.

But, this article is concerned with a wider lens and one question. How should the state ‘sustain and encourage the arts’ going forward if we agree that they are “essential to any complete national life”?

Let’s begin with that phrase “the arts” and take a step back in history before we look to the future.

The foundation of the Arts Councils that we know today was laid in 1940 when a Committee for Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) was set up during the war “..to carry music, drama and pictures to places which otherwise would be cut off from all contact with the masterpieces of happier days and times : to air-raid shelters, to war-time hostels, to factories, to mining villages…the duty of C.E.M.A. was to maintain the opportunities of artistic performance for the hard-pressed and often exiled civilians.” wrote John Maynard Keynes. C.E.M.A’s initial aim was to “replace what had been taken away” by war but “we soon found that we were providing what had never existed even in peace time.”

This led to The Arts Council of Britain being founded in 1946. The shift away from ‘the arts’ being seen as a private good, a luxury affordable to only a minority, to a public good accessible and available to all had begun in earnest. However C.E.M.A’s, and in turn the arts council’s, vision and objective of supporting and “spreading” what many termed ‘elite culture’ or ‘high art’ created tensions and sparked criticisms which have continue to reverberate to this very day despite the significant change of direction and scope with the appointment of Jenny Lee as the first Arts Minister in 1964.

The subsequent period from the appointment of Lee to the beginning of the Thatcher premiership is often regarded as the “golden age” of the Arts Council, with increased access to artistic practice, support for avant-garde art forms and “a redefinition of popular culture away from reductive assignations to the commercial sphere.” State funded arts thrived for over a decade, including community arts and theatre-in-education, reaching a high point in the late seventies. However with a political backlash to Keynian economics at the end of the seventies and the prioritisation of a market led economy came a backlash to the very principles and vision which had formed the arts council. The principle of state sponsored cultural production and cultural democracy were challenged and a new cultural strategy of reduced public expenditure and the growth of private sponsorship and philanthropy and commercial imperatives began and has continued ever since.

The notion of arts and culture being a private good gained new ground and a three pillar funding model for the arts was established – state, philanthropy, commercial – which has remained mainly unchallenged ever since as I discussed in a blog back in 2015. Those commercial imperatives meant that the ‘creative industries’ were separated out from arts and culture and heritage and treated as entirely separate because they could be monetised and were therefore apparently worth a different level of investment without any seeming understanding that the creative sector is one ecology.

A performer, a writer, a designer, a director will move across art forms and creative genres from screen, to gaming, to animation and then across all aspects of live performance because it is one ecology. A visual artist will work with a recording artist a spoken-word poet, a musician, a tightrope walker, a games designer and a film director and see no boundaries. As a freelancer I create work with and for theatres, venues, art galleries, museums, schools, colleges, film and theatre festivals and across multi-media platforms. I work in both participatory and community arts settings as well as with ‘high art’ organisations and across the ‘creative industries. Because it is one creative sector. Within this ecology I also include publications like this one which are a vital component of a healthy creative sector providing a critical lens, a platform for creative voices and public access to the work.

A starting point therefore would be to accept and acknowledge we have one creative sector and move on from the pre-war term ‘arts’ and the more recent term ‘culture’, both of which alienate and segregate. Instead of unhelpful and artificial categories imposed on us – ‘the creative industries’, ‘the arts’, ‘the arts and cultural sector’, ‘visual and performing arts’ – could we begin to use one term to describe one ecology inside which all artists and creatives exist? The term the Creative Sector would perhaps suffice?

A second stage would be to address the unhelpful requirement for the sector to constantly articulate and defend its very existence. Creatives have been in a position of defence in the UK for decades, since Margaret Thatcher came to power and called for the arts and cultural sector to make the case for culture and define it in economic terms. Over forty years later we are still required to constantly re-articulate and re-evidence the value and impact of arts, culture and creativity to society and spend scarce resources having to explain and defend what every individual knows is fundamental to being human. The creative sector has become increasingly mired in evidence gathering and data collection to prove it’s worth and very existence to society.

There is endless qualitative and quantitative evidence of the impact that access to, and participation in, creative arts and cultural activities has on everything from mental health and well-being to tackling anti-social behaviour and polarisation and increasing civic engagement and cohesive communities. The evidence also points to the benefits of using the arts and creativity in rehabilitation, conflict resolution, team building and as a diplomatic tool and ‘soft power’ and as the most effective and low-cost strategy for urban regeneration to name just a few areas.

If we accept all of the above we can move on from the ‘why’ to the ‘how’ and begin to look at how we fund that one ecology, that one creative sector.

The vision of one organisation to fund that one ecology which was arms-length from the government was a strong and clear vision. Unfortunately the notion of creatives being funded at arms-length has been recently undermined by Westminster through the levelling up funding which leapfrogged devolved parliaments and arts councils. It has also been somewhat undermined in Wales by the creation of Creative Wales which is a government run agency which has also further cemented the false divide between the ‘creative industries’ and the arts and cultural sector’.

Whilst I applaud Creative Wales creating a long overdue memorandum of understanding with the Arts Council of Wales, it still does not answer the question of why we need two separate organisations. Particularly in a small nation where we need less structures and bureaucracy and more collaboration, partnership working and joined up thinking if we are to meet the goals and ways of working set out in the Well-being of Future Generations Act. If we accept we have one ecology, one creative sector then surely we need one independent arms-length constitution free from red tape to invest in that sector and with enough money to do so properly?

If we accept the return on investment into the creative sector and that it is the fastest growing sector in the UK economy it would seem to be a no-brainer to invest in that winning horse.

The Arts Council of Wales in the most recent investment review had applications to the total of almost £54 million submitted to them. This is a good indicator of how much is required. The current funding available to Arts Council Wales to spend on core funding for arts organisations across the whole of Wales is less than £30 million. This includes cutting their own overheads to increase the spend from the previous £28.7 million.

To put this in context the Welsh Government has an annual budget of 21 billion. The Arts Council received £33.3 million in 2023/24, a 1.5% decrease from the previous year. That amounts to 0.15% of the overall budget. To give further context the average government spend on culture in European countries is 1% with some reaching 2.5%. The UK and Wales is shockingly below this average and yet as a sector we consistently punch above our weight on the global stage. Such low investment is simply not justifiable. Rather than backing the winning horse we are neglecting and under-nourishing it to a fatal degree.

If we can own our own narrative and terminology then the question would change to – ‘How do we sustain and encourage the creative sector going forward?’

To summarise my answer to this question is in five parts:

- We first need to accept that the creative sector is the third pillar of our civilized society as forged post World War II. Those three pillars are a state funded NHS to nurture our health, state funded education to nurture the minds of the next generation and a state funded creative sector to nurture our souls, our spirit and give us a means to both express and understand ourselves and each other.

- We need to acknowledge and accept that the creative sector more than ‘washes its face’ when it comes to the economy as was evidenced once again with recently recent figures from DCMS.

- We need to move from the ‘why’ to the ‘how’ and acknowledge and accept the sector’s huge worth, value and benefit to society, beyond economical, and stop asking artists to prove over and over again how they can impact and benefit society.

- As a sector let’s start calling ourselves one thing. Let’s own the language and the narrative. Let’s call ourselves the Creative Sector. Let’s accept and celebrate all the variation of creativity that exists within our sector and acknowledge that we work within one ecology that requires all of its parts to exist and thrive.

- Then together as once unstoppable force let’s begin to collectively demand a simpler state funding system and a minimum of 1% of the annual budget that can actually sustain and encourage that creative sector to flourish and thrive within the UK and on the global stage.

Yvonne Murphy is a freelance theatre director and producer who runs Omidaze Productions and is the creator of The Democracy Box and The Talking Shop.

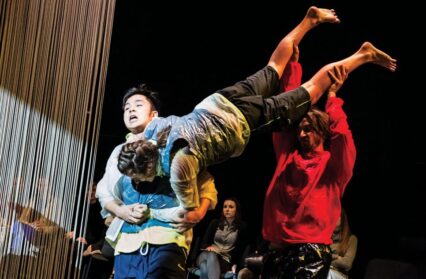

Header Image: iCoDaCo International Contemporary Dance Collective (Jones the Dance and international partners) courtesy of Katarzyna Machniewicz.

Arts Council of Wales investment Arts Council of Wales Arts Council of Wales investment