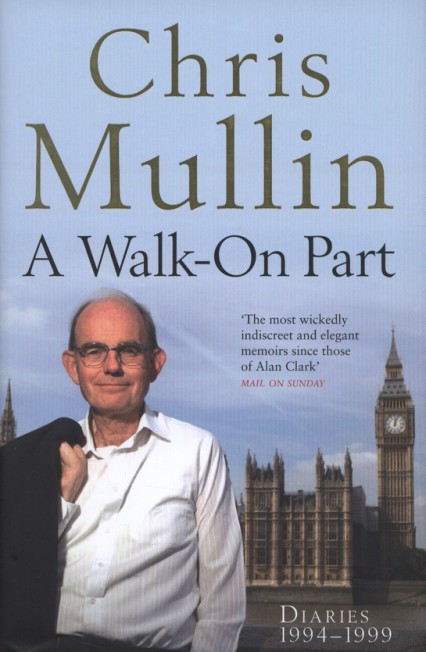

Adam Somerset delves into A Walk-On Part; the 1994-1999 diaries of the long serving Labour MP Chris Mullin.

‘Today, Britain’s electorate is more polarised, less aspirant, and, overall, more socially conservative, than it has been for decades.’ So writes a theorist for the Labour Party in June 2012. Somehow it does not sound convincing. One virtue of A Walk-

He observes the numbing effect of unbroken one-

In his constituency surgery he encounters (23 July, 1999) a twenty-

by Chris Mullin

496pp, Profile Books

Chris Mullin’s two previous volumes described his time as backbencher elevated to minister through to his retirement. A Walk-On Part covers the years 1994-1999. As a prequel it contains much that is pleasurably ironic. As in X-Men: First Class or Rise of the Planet of the Apes it has many a moment where the reader may smile knowingly at how the future is destined to turn out.

He sees (27 June 1994) Alan Milburn as ‘bound to be a minister’ but doubts ‘that he’ll ever make the Cabinet’. When he meets a press baron or fellow parliamentarian it is up to the reader to smugly know who is now behind bars. ‘We’ve thrown our hand in with the City, as opposed to manufacturing,’ says David Blunkett (27 June 1995).

Chris Mullin includes a rare footnote from a meeting with television tycoon Michael Green (8 March 1995). ‘He was accompanied by a rosy-

Mullin’s deep, and campaigning, interests include the media and the justice system, when it has practised injustice. Early on he tackles his Leader on media ownership: ‘I suspect he shall err on the side of caution,’ (23 June 1994). This is a different kind of premier from the one whom we perceive today. A conversation (15 June 1999) with Paul Stinchcombe moves to the subject of fat fees for lectures after office. ‘Paul, you don’t understand,’ Cherie is quoted as saying, ‘I’m married to an idealist. When Tony retires, he wants to go and teach in Africa.’

The New Labour project may be looking to redefine itself in 2012 but Mullin records the struggle of its creators to make it happen at all. 31 Dec 1994: ‘No day seems to pass without news that some old policy or principle has been discarded. I only hope we have something to replace them with and so far that is not at all clear.’ He hears Donald Dewar on Today explaining the stakeholder society (13 January 1996): ‘the sad truth is that it is all meaningless claptrap.’ But in the battle over Clause Four he is unideological (30 January 1995). He knows South-

Many a truth about politics is sifted through the diaries. A Home Office Minister (17 Mar 1999) confides ‘about eighty per cent of public service computer contracts have gone wrong.’ The full record of the part played by messianic IT salesmen in this period of government has yet to be told. He observes many a human truth too. 25 November 1994: ‘Dealing with Gordon was the first big test of Tony’s leadership and he’s failed miserably’. On Robin Cook (27 January 1999) he writes, ‘Confident, robust, impressive. He was well-

A good diary is a life in full. A resolution for January 1st, 1998 reads, ‘never forget there is life outside politics.’ He suffers an agonising stomach condition that is slow to be diagnosed. After an all-

Back in Parliament he observes of the shadow chancellor, ‘When most of us go home to our families at the weekend he goes home to work out how to get on the weekend news bulletins’ (21 March 1995). Some MP’s in opposition can hardly bother to turn up. A Whip tells him ‘they have to be kept sweet by being given foreign trips, good offices and so on,’ (22 November 1994). In Europe he records without comment an interpreter at the European Parliament: ‘some of the Greek members were just turning up, signing in and going home again,’ (27 September 1994.)

The great days of Cabinet government may never have existed. Chris Mullin is reminded in reading Harold Nicholson’s Diaries of how often a previous prime minister ‘was to be seen in the Smoking Room – How seriously Churchill took the House of Commons,’ (3 April 1999). By comparison Rhodri Morgan (5 November 1997) talks of the culture of leaks and off-

Chris Mullin is a man with an admirable record outside politics. He knows, as David Heathcoat-