In her famous critical study, On Photography (1977), Susan Sontag explores the nature and implications of photography as an art form. Among her simplest and most profound observations in this work is the idea that:

To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.

It is interesting that Sontag understands and deconstructs photography here through the imagery of water: in terms of ‘freezing’ and ‘melting’. It is as if the protean character of water captures precisely the very ‘mutability’ in which, Sontag suggests, the photograph inevitably participates.

English poems by Tony Curtis

Welsh poems by Grahame Davies

Photographs by Mari Owen and Carl Ryan

Gomer

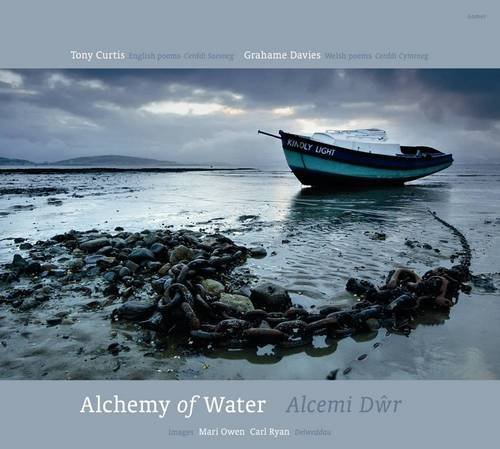

Gomer’s collaborative book-project, Alchemy of Water | Alcemi Dŵr, explores the dialogue between water and photography further in a stunning series of images that reflect the ubiquity and fluidity of this element in the Welsh landscape. The photographs, by Mari Owen and Carl Ryan, encompass a wide range of subjects and geographical locations: from the glassy surface of Llyn Gwynant in Snowdonia, to a rapid, swollen river in the Vale of Neath; icicles glittering on the branches of a petrified tree in the Brecon Beacons, to grey and coral clouds amassing over Trawsfynydd Nuclear Power Station in Gwynedd; a boat stranded at low tide on the sand at Mumbles, Swansea, to shelves of smooth wet slate catching the light at Cwmorthin quarry, Blaenau Ffestiniog. Each image testifies to the transformative, capricious character of water and to its vital, ‘alchemical’ presence and influence within the natural, social and historical topographies of Wales.

According to Sontag, photography’s ‘participation in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability’ makes it an essentially ‘elegiac art’. And, certainly, a number of the photographs in Alchemy of Water | Alcemi Dŵr, such as the images of Trawsfynydd Nuclear Power Station and of rain clouds above a ruined slate mill in Porthmadog, are, in Sontag’s words, ‘touched with pathos’. Just as, in Sontag’s analysis, photography is absorbed into the creative and critical discourse of poetry – of the elegy – moreover, Alchemy of Water | Alcemi Dŵr represents an artistic space where the boundaries between photography and poetry are permeable. Accompanying and responding independently to each photograph in the book are short, distinct poems in both English and Welsh by Tony Curtis and Grahame Davies, respectively. Each combination of verse and photograph constitutes a site of overlapping – of alchemically interacting – ‘images’, in Ezra Pound’s sense of the word. ‘An “Image”’, Pound argued in Imagisme, ‘presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instance of time’. Although Pound was referring explicitly to the poetic image here, his analysis seems equally applicable to the kind of skilled and ‘intellectually’ and aesthetically considered photography exhibited in Alchemy of Water | Alcemi Dŵr. Indeed, in his introduction (Davies also provides an introduction in Welsh), Curtis identifies the ‘imagist poem’ as a ‘reference point’ for the poetry in the book, along with the traditional Welsh-language poetic form, the englyn; folk verse [and] haiku’.

In response to a photograph of mountains mirrored in the still water of Llyn Dinas, Berddgelert, Snowdonia, at dawn, for example, Curtis writes:

As morning’s mist

lifts and flies,

water and light contrive

to double the world.

An image of slate in Cwmorthin quarry, on the other hand, prompts the following response:

In the land of slate-blue, slate-black,

slate-brown, slate-green,

these hands of low cloud

bearing a platter of light.

Grahame Davies’s Welsh-language poem accompanying the Cwmorthin quarry image demonstrates the added alchemy of language – the creative exchange between Welsh-language culture and English-language culture – that bubbles up like a spring in this porous artistic space. I have only a partial knowledge of Welsh; and yet in hearing and translating (albeit perhaps, at times, crudely) this and Davies’s other Welsh-language poems, I sensed that I myself was participating, in a unique way, in the overall (to cite the book’s definition of ‘alchemy’) ‘magical process of transformation, creation or combination’:

Yng ngwlad y llechen las a’r llechen frown,

ar lethrau’r llechen werdd, a’r llechen ddu,

ar ddirwnod pan f’or awyr lwyd yn drwm,

mae’r glaw yn addo’i arian byw i mi.

Alchemy of Water | Alcemi Dŵr, then, is an engaging, often beautiful, and innovative exploration of the relationships between water and landscape and word and image. It is also a celebration of Wales and Welsh culture and of the creativity that they inspire. And while I personally felt the relative lack of ‘images’ of South-East Wales in the book, I am heartened by Curtis’s observation that

There is no corner

water cannot turn

no darkness

water cannot lighten.