Travel has always been important to me. I spent a lot of time exploring Asia, Eastern Europe and South America in my twenties and India has always been high up on my list of places to travel. But this time I did not just want to visit; I wanted to travel there as a writer and a musician (I am a flautist) and in a way that I could connect creatively to the people, the history and the incredible culture of this dichotomous and amazing country.

I began to read into Indian folk stories, like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana and I became engrossed in the mysticism and aesthetic of Indian art culture – especially in the south, with its distinctive musical flavours and radical differences from the North Indian styles, which seem more prevalent in the UK and Europe. I began to wonder how Welsh literary and musical traditions would translate over in such a huge, polytheistic and multicultural society and the beginnings of an idea began to form. But I would need some help.

Dr Robert Smith is a composer, multi-instrumentalist and respected academic. Like myself he is a second language, but fluent, Welsh speaker with a passion for Welsh history, musical forms and folk culture and, more importantly, with a history in studying and performing Indian music.

Rob’s previous work with Indian musicians had focused primarily on the Hindustani music of the North and so he had a great interest in exploring the art music of the South – Carnatic music. Working together we began to formulate a plan: wouldn’t it be fascinating to take our mutual enthusiasm and knowledge of Welsh culture into the hot, frenetic and completely alien society of India’s musical practitioners? How much could we learn about Carnatic music by sharing our own musical background?

After a little digging around we discovered that very little work has been done to combine or fuse Western musical traditions with the Carnatic; the two styles seem, on the surface, worlds apart and more than just geographically. For example the notion of harmony does not feature in the majority of Indian music, while their signature flamboyant ornamentation is very rare in traditional European styles. Indian musicians seem to have very little use for notation, learning instead through detailed and interconnected aural traditions and seemingly complex rhythmic structure and improvisation – closer to Western jazz than anything, really.

This was starting to get interesting. We began to realise that the only way to develop a real understanding of this completely foreign system of music would be to immerse ourselves fully in South Indian culture. We would have to visit.

Divakar Subramaniam is from Chennai, South India. Having lived and worked in Wales with Rob at University of South Wales Atrium campus as PhD researcher and lecturer he seemed to be the ideal person to contact. Now working back in Chennai at his own School of Indian Film Music, Divakar was delighted to be involved with our idea. With his musical and literary contacts in India, plus his recording studio and musical expertise, we were able to formulate a plan of action: Our aim was to travel to South India and experience as much art culture as possible. We would introduce some Welsh music to the musicians we met along the way, learn about South Indian storytelling, art, dance and music and, using our experiences, create an original recording informed by the traditions of both cultures.

We also aimed to document our findings in order to create educational materials based on what we had learned for dissemination back in the UK. Using social media would allow us to share up-to-the-minute activity with people back home, as well as to connect with people we met along the way.

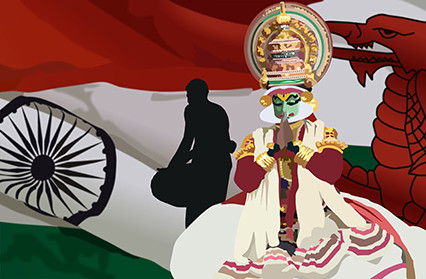

Wales Arts International provided the funding to make our trip possible, with additional support from The School of Indian Film Music and USW – we really were going! The day was set for the 17th of March 2014, when I would travel on ahead alone to Kerala to begin the project by taking a closer look at Kerala’s Kathakali dance traditions.

Kathakali dance is specific to the state of Kerala and involves elaborate make-up and costuming as well as extensive physical and emotional preparation from the dancers, who have to train for many years before performing the dances. The dances physicalise stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata and performances traditionally last for up to eight hours. Generally only royalty and the socially elite were permitted to watch the dancing, which involves detailed movements of the eyes and hands to signify meaning, emotion and action. The music is incredibly important at these performances and dancers are accompanied by a singer, mridangam and tabla. There is also usually a shruti box present. I was able to attend a more accessible performance of the Kathakali, for which a narrative outline and explanation of the movements was provided. This performance would introduce me to the idea of raga and whet my appetite for understanding more about Indian music.

Raga is the essence of a piece of music. Where western music has modes, keys and scales; notation to indicate rhythm, pitch, tempo; symbols to represent ornamentation and direction to suggest mood, the raga encapsulates all of these things as well as tone, style and feel. There are many thousands of them; dedicated practitioners could hope to know only a small portion in a lifetime’s study. The ‘Tala’ is the rhythmic structure in each raga and it tells the players the rhythms which should be used, where the raga informs the players of everything else; which notes should be ornamented and how, the appropriate tone, and mood etc. Ragas represent sunrise, sunset, sleeping, waking, dancing, happiness; there is a raga for every mood, every event, every emotion and many people believe in the healing powers of certain ragas.

After the Kathakali performance I spoke with the musicians and the man who runs the Kathakali centre in Fort Cochin and arranged to return the next day at 7am for morning raga meditation. This comprised tabla, chanting and singing and an electric shruti box to drone throughout to induce a trance-like state. I was instructed to sit cross-legged on the mat beside the musicians and to listen to the music, eyes closed. The piece was a sunrise raga, designed to prepare performers and meditative participants for their day. This was accomplished, in my limited understanding, by upward inflections and ‘hopeful’ intervals in the singing. The rhythms were quick in tempo, rising gently as the piece gained fervour. The meditation session lasted for 90 minutes and I was eager to speak with my hosts at the end.

They explained about the raga and how it is at the centre of Indian music – it is the basis for learning, performing, improvising and everything musical. I was excited to learn more about this from Divakar in Chennai and to meet the musicians who practised them so fluently.

It was time for the next stage of my journey, so I made my way overland to the crazy, chaotic, lively and noisy city of Chennai to meet Rob and Divakar. First of all we visited Divakar’s school and recording studio, where he talked us through the extremely complex system of rhythms used by Carnatic percussionists. Rhythmic patterns are established in pieces through ‘chains’ of simple structures which ‘inform’ one another to create the structure of the music as a whole – in this way Carnatic musicians are able to perform with musicians they have never met before, let alone played music with.

I struggled to keep up with the complicated variants and names flying around, but this lesson in the basics prepared us to meet ‘Ghatam’ Karthic, Chennai’s most renowned Ghatam player. A larger than life character, full of laughter and music and enthusiasm, Karthic introduced us to his instrument. The Ghatam is a kind of tuned clay pot used for percussion. While the hands and fingers can create impressive rhythmic patterns, a Ghatam player can use his or her stomach to add dimensions to the sound by covering and uncovering the top of the pot. He spoke about the compulsive nature of rhythm to a percussionist; about how he found himself measuring his steps and subdividing the beats and working out the mathematics of complicated percussion flourishes in his head when he walked and about how anything with a steady rhythm can infiltrate your thoughts and set you to counting and tapping compulsively in everyday life.

We were lucky enough to improvise some music with Karthic and we selected a Welsh favourite: ‘Ar Hyd y Nos’ as a platform to work from. With myself playing the melody on flute, Rob playing major thirds above and joined by Karthic on his Ghatam we played around with rhythms, ornaments and improvisation across contrasting musical worlds.

Next on our busy agenda was a meeting with film singer Jaya. Venturing into the pop music scene in India gave us a real insight into just how important music is in Indian media; for the most part songs sell films. People will hear a tune which will then entice them to go to see the film – precisely the opposite to the usual turn of events in Western culture. Speaking to Jaya also allowed us to look at the role of women in the music industry.

Traditionally female vocalists are expected to work to their male counterparts, reaching high, often shrill pitches in order to appear feminine and to offset the deeper male voice. Jaya told us that in more modern films it was becoming acceptable for women to use a range of pitches in their singing and to produce a more varied and individual sound.

As with all culture, the rise of the internet, file sharing, streaming and downloads, the Indian film music is changing too, often seeing recording artists bypassed in favour of the cheaper, computer generated music. This method also saves time and can be more easily uploaded and shared online. Times are a-changing and exciting developments are going on right now in the Indian movie industry.

That night Jaya invited us to see her perform at a club, where she sang Bollywood and Kollywood hits to a backing track and a genuinely delighted audience. There was not one member of the audience who was not singing and dancing by the end of the evening as she recreated well-known hits from their favourite musicals. She even dedicated her only English language song to Rob and myself!

Using what we had learned from Karthik, Divakar, Jaya and the Kathakali performers Rob and I began to consider ways in which we could create a piece of music from these wildly different musical systems. What we needed was to talk to someone who was familiar with both the Western system of music and the Carnatic. As our initial research had shown us, there were very few people who are able specialise in both, as each system is detailed, complex and radically different; understanding the two would require a lifetime of dedicated study and practise. VS Narasimhan is one of the few musicians who not only understands, performs and teaches both musical systems, but composes unique fusion pieces drawing on his favourite elements of both. We were able to visit him at his home in Chennai, where he spoke about his experiences, improvised for us and showed us some of his compositions.

Having studied Carnatic music as a violin player VS went on to explore the harmonies, structure and notation of Western music, exchanging the traditional Indian squatting position for playing for the upright European classical stance. Fascinated by the harmonies in the music VS has spent his life creating traditionally Western harmony structures based on Indian ragas for his string quartet – often with startling and fascinating results; his compositions are thoroughly unique and often witty in their virtuosity, like this Dave Brubeck inspired piece Count Five.

VS is working to create a chamber orchestra to further develop this fusion work. He is training students to understand and appreciate both schools of music and to create new, original music from their work. His efforts astounded us all and we left his house inspired and brimming with ideas for our own composition.

Back at the studio Rob and I, drawing on our conversation with VS, began to experiment with Welsh music in Indian ways – for example we chose to examine several basic and well-known ragas and to use elements of them in our playing; without having had the opportunity to cultivate a deep understanding of ragas we decided to use the basic element which we could understand: the mode. Choosing a Welsh lullaby, Suo Gan, we experimented with a number of raga modes including a palindromic raga called ‘Māyāmāḻavagauḻa’, and modes which ‘translate’ to Phrygian, mixolydian etc. in the Western system. We played and recorded the original tune in each of these ragas.

Our aim was to create a piece of music that would travel with us and show the things we had learned and the discoveries we had made. We outlined the sketches of a structure for our piece: we would play Suo Gan in its original key, then change to the mode of the raga known as Kharaharapriya as we explored India and her music and then back to the original key, back to Wales. This was exciting, but it was still just an outline – we needed help.

Working once again with Karthic and Divakar we returned to studio to create our piece. Divakar suggested we include traditional Carnatic instruments alongside our flute, clarinet and soprano saxophone recording to complete the fusion. Karthic recorded a series of incredible rhythms to accompany our piece, each more intricate than the last and Divakar added his signature Ganjeera sound to it, to give it a liquid fluidity.

The icing on the proverbial cake was the addition of improvised bamboo flute dancing over the melody. A young, up-and-coming flautist called Shruthi Sagar came along to an early morning session at the studio. With rapid Tamil flying between Divakar and Shruti the light, ornamented playing of the flute completed the truly Indian sound we had experienced during our time in Chennai. Backing lines extemporised by Rob and myself kept the Western musical identity going steadily throughout, with a little nod to Rob’s own signature jazz sound.

Divakar’s amazing mixing and recording work means that the track is now up on Soundcloud. The project is on-going now that Rob and myself are back in the UK. We are currently working on pulling all of our research and experience together to make educational resources. We hope to share all of the amazing things we have learned online, using video, sound clips and photos and we are hoping to develop some workshop material for practical dissemination in the future.

We would love to chat with some Carnatic musicians in Cardiff, too, with a view to continue to develop and perform back here in the UK, but most of all I think we have both been bewitched by India. We are dying to go back and dig a little deeper into the richly detailed complexities of Indian music.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis