Rosie Couch discusses the issues surrounding the UK Government’s perpetuation of diet culture through the introduction of their ‘Better Health’ campaign in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

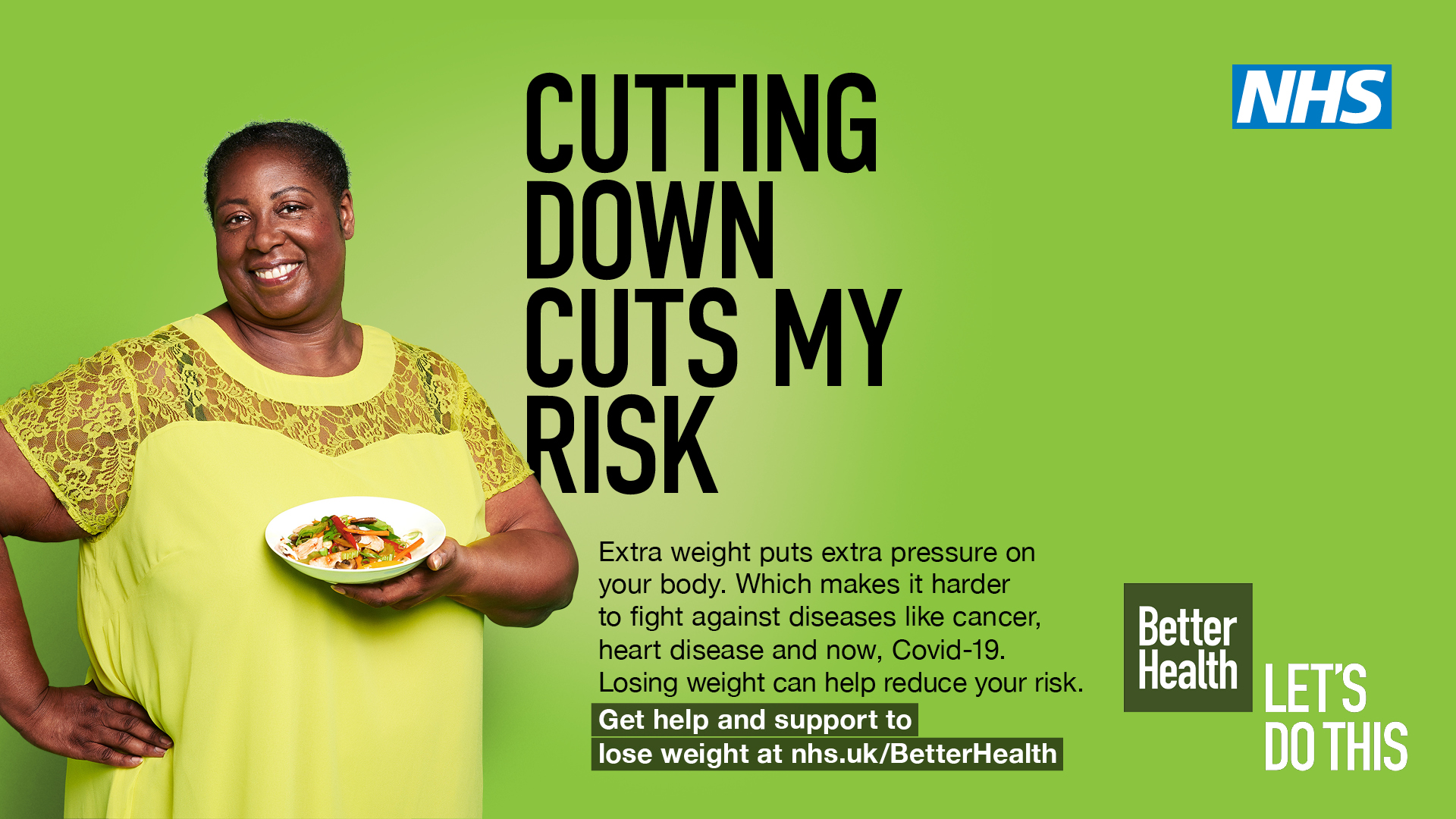

At the end of July, the UK Government published a ‘new obesity strategy’, detailing a ‘package of measures and ‘Better Health’ campaign’ designed to help the people of the UK to lose weight and, apparently, ‘beat coronavirus’. The intertwining of this strategy with coronavirus – figuring individual people’s body weight as a critical cause of the pandemic’s escalation (rather than, I don’t know, constant U-turns, ineptitude and hypocrisy from the government supposedly leading us through it) is sly, deliberate and dangerous. Putting the pandemic to one side for a moment – if that’s possible – my first thought when reading about the campaign was: who is this strategy going to harm?

Beat – the UK eating disorder charity – estimates that approximately 1.25 million people in the UK have an eating disorder. Anorexia, in particular, has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric condition, as well as causing potentially serious health issues, alongside bulimia and binge eating disorder. With these statistics in mind, the idea of a ‘Better Health’ campaign consisting entirely of weight loss measures, as well as the inclusion of calorific value on menus and bans on adverts and offers for certain foods, feels negligent at best, and highly dangerous at worst. I’ve never been diagnosed with an eating disorder, despite struggling with disordered eating since my late teens. I’d say I’m pretty firmly in recovery now, but, as I will suggest later, it’s a process that is far from linear. At my lowest weight, I was eating around 500 calories a day, my hair was falling out in clumps, and my hands were constantly numb. When I finally listened to my mum and accepted that, yes, something was wrong, I visited the doctor. After being weighed and assured my Body Mass Index was in a healthy range, the GP told me to stop crying and definitely stop smoking. Despite how horrendous I think that treatment was in retrospect, I am still speaking from a position of enormous privilege. When fat people have health problems, their weight is consistently attributed as the sole cause. Additionally, BMI, despite evidently being an inaccurate measure of health, is presented as a barrier to trans and non-binary people wishing to have gender confirmation therapy and/or surgery. My intention here is not to criticise the NHS – who, as we are all now aware, is chronically underfunded and overstretched – but rather to emphasise how the priorities of the government’s campaign serve a particular narrative of weight and health, while ignoring a plethora of other issues.

My own experiences with disordered eating have been intricately linked with the desire to feel in control. When, as it tends to do, life felt too chaotic, restricting how much I ate was an easy and somewhat addictive way of restoring a kind of order. You eat less, you become smaller. The problem is, this reality of becoming smaller extended to so many other areas of my life and selfhood. My social life became smaller as I feared what the government campaign describes as the ‘hidden calories’ in alcohol, or in restaurant food. My mood was constantly low, meaning that important connections with those around me were also affected. Despite becoming closer to the way I thought that I wanted to look, and the images of femininity that dominated, and still dominate, the cultural images that proliferated around me, my confidence also continued to diminish. My energy, my will, my desire, all smaller. Simultaneously, because we live within a culture that shames weight gain and encourages and elevates dieting and slimness, I was praised by those around me for how much weight I had lost. The other losses, the loss of who I was before, the connections that I had – ultimately, the things that make life liveable and enjoyable – have no space for expression in a culture that deifies thinness.

Similarly, no space is given to a broader understanding of health and weight in the government’s newly unveiled plans. In fact, I suggest that the campaign itself is highly invested and intricately intertwined with the diet culture that already proliferates all around us. The fact is, diets are not sustainable. Though they may enable you to lose weight over a short period of time, studies show that the majority of people who diet gain back the weight that they have lost, or more. They aren’t sustainable, because they aren’t supposed to be. For example, Slimming World promises a weight loss regime involving no calorie counting and never feeling hungry. You can eat as much as you like of their designated ‘free’ foods. And, so that you don’t go ‘off track’, you can have small portions of foods that are ‘least filling’ and ‘higher in calories’, also known as ‘syns’. When the foods ‘allowed’ under such a diet are so abundant, Slimming World members who fail to sustain their weight loss are encouraged to turn their criticisms inwards: ‘If I can’t follow this plan, I am the problem’. The thing is, though Slimming World promises a plentiful diet plan, ‘free’ from restriction – even before we bother interrogating the thinly veiled theological undertones inherent within the categorisation of foods as ‘syns’ – there is a clear division between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods. And this kind of demonisation of certain food groups is restrictive. Restriction does not make cravings go away – it enhances them. The labelling of foods as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ also serves to create an ‘all or nothing’ mentality. If you slip and eat an ‘off-plan’ snack or meal, you might as well eat ‘badly’ for the rest of the day and start afresh tomorrow. And thus the cycle continues.

Diet culture is an industry which sets consumers up to fail. And, when they do, they return to Slimming World, or a suitable alternative. Perhaps it’s intermittent fasting, or the 5:2 plan. It is an industry that perpetuates its own failure, implicitly designates that failure to individual consumers’ lack of willpower, and thus provokes them to continue participating. Within diet culture, dieting itself is not the problem, you are the problem. As a system, it is inextricable from capitalism and neoliberalism. The government’s ‘obesity strategy’ and ‘Better Health’ campaign states that ‘tackling obesity is not just about an individual’s effort, it is also about the environment we live in, the information we are given to make choices; the choices that we are offered; and the influences that shape those choices’. Despite what the above might infer, the strategy and campaign hinges on the same demonisation of food, alongside a broader, and willing, ignorance towards socioeconomic factors which contribute towards public health. Their measures include: banning ‘unhealthy’ food adverts before 9pm, ending buy one, get one free promotions on foods that are high in fat, sugar and salt, and labelling the calorific information on alcohol and restaurant menus. Again, we have ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods laid out as opposing binaries, accompanied by the notion that, before this campaign, calories have been hiding out sneakily, waiting to trick our ill-informed minds into overeating. The overarching message is that certain foods are not to be trusted, and, when we want to eat them, neither are our bodies. There is no recognition of the various socioeconomic factors that dictate what people can eat, when, and why. When I was growing up in a single parent household, with my mum having to find the money to feed herself and two teenagers, the focus was on finding filling, satiating foods. The barring of buy one, get one free promotions would have affected our budget drastically, as it will affect those who rely on such reductions now. She didn’t have the time to cook from scratch after working each day. It was much cheaper to buy a couple of frozen pizzas than it was to fill the cupboards with the accoutrements needed to prepare such meals. Following the press release for the government’s new guidance, voices from one side of the debate on Twitter cited the low prices of fresh produce, such as carrots or potatoes, as support for the idea that people eat ‘bad’, processed foods because they are lazy or uneducated. Such opinions are tangled up with shaming practices around class and food. How do you make a meal out of carrots and potatoes alone? How many mouths would it feed? Why can’t people with less money enjoy the food that they eat? How can you prepare fresh produce when you don’t have an oven, or a hob, or a fridge to store it in? What if you’re working two jobs to keep your head above water? What if you need to focus on eating the amount of calories that you need to survive? Instead, we’re being encouraged towards pubs and bars in the name of supporting the economy. And, obviously, a huge part of this support has been the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme. I’m not the first to highlight the blatant hypocrisy of such a scheme being pushed by the government alongside exhortations to lose weight, so I won’t dwell on it here. The point is, though the government claim that their strategy is ‘not just about an individual’s effort’, we find ourselves back with the individualisation inherent within capitalism and neoliberalism – it is up to you as a consumer to support the economy, but you as an individual are also the problem.

When thinking about writing this piece, I wondered (half-jokingly) whether we would see reports of Boris Johnson doing the Couch to 5K plastered across news headlines. The very next day, I found the feature ‘Boris Johnson hires personal trainer Harry Jameson’ when scrolling through the day’s reports. This report is not news; it is flagrant propaganda. We are supposed to see bumbling Boris as someone who is struggling along with us. He has been infected with and ‘defeated’ coronavirus, and now he is following his own advice after admitting that he was ‘too fat’ when he became unwell. Obviously, it is impossible to feel that Boris is ‘a man of the people’, and these reports have only emphasised the divide. His employment of a celebrity personal trainer, and the fact that he, no doubt, has plenty of people to cook for him, show just how wilfully out of touch he is with the lived realities of the people that he seeks to govern.

Also present within both diet culture and the government’s campaign is a rampant undercurrent of fatphobia. Fatphobia equates fatness with ill-health, undesirability, and laziness. It is a discriminatory, shaming, and stigmatising practice. These kinds of behaviours towards fat people also heavily intersect with racism and sexism. Instagram is one site where such an intersection of oppression has recently played out for all to see, prompting plus size model and activist Nyome Williams to campaign for the platform to review their semi-nudity policy. Nyome identified how, while all bigger bodies are treated differently in a fatphobic culture, bigger black bodies are discriminated against even further. Instagram has platformed accounts such as those belonging to Dan Bilzerian – featuring images of the man himself draped in and surrounded by scantily clad, thin, white women – but images posted by Nyome of her own body, as a black, plus size, woman, were repeatedly censored. Furthermore, when Nyome’s campaign was well underway, it was also co-opted by white women who, despite also being plus sized, still have privilege within the ‘body positivity’ movement and culture more broadly. Despite these knotty tensions, the #iwanttoseenyome campaign succeeded in influencing Instagram to review their policy. Nyome and her supporters’ work stands as an important collective stride towards the visibility of plus-sized people living life happily and loudly, in a culture that venerates thinness and whiteness. (For more details on the above, you can view Nyome’s ‘Support BW’ highlight on her Instagram: @curvynyome).

The dominant message of diet culture is as follows: If you weigh less, your life will be better. This idea also forms the refrain of various eating disorders. The government’s new strategy takes it one step further – if you weigh less, you’ll be healthier and happier, but you can also help to defeat a global pandemic. I’m going to visit their press release one last time, to highlight the suggestion that ‘it’s hard to make the healthy choice if you don’t know what’s in the food you are eating’. Instead, I want to propose a different message that has helped me to continue in moving beyond diet culture and disordered eating: the healthy choice is the choice that honours hunger and appetite. Your body knows what it needs, whether it’s pizza, broccoli, chocolate, quinoa, whatever. An unhealthy choice, on the other hand, is pummelling people with diet culture during a pandemic, while remaining completely ignorant to the sprawling socioeconomic factors which influence public health.

I mentioned earlier that recovery from disordered eating is not linear. It’s messy, but so are bodies and, without leaning on cliché too heavily, so is life. Perfection isn’t possible and, perhaps, bodily ambivalence might be a more productive way of existing in whatever size your body wants to arrive at when you’re living the life that suits you best. So, both eating disorder recovery and a departure from diet culture are also somewhat introspective. You have to ask yourself: what do I value? Who is important to me? Do they give a shit what dress size I am? Food is more than ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Food is the meals out with friends that aren’t bookended by restrictive practices, the pancakes piled with toppings and dripping with syrup that I eat with my boyfriend on a Sunday morning, and the ice cream I wish that I’d enjoyed with my mum at her favourite beach. The government’s strategy proposes knowledge as a means of empowering people to make the right choices. For me, however, learning about diet culture as an industry, and how it intertwines with systemic oppression has been infinitely more empowering.

Rosie Couch is a contributing editor to Wales Arts Review and co-presenter of the Wales Arts Review podcast.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.