Adam Somerset takes a look at, Biblical Art from Wales, a collection of welsh art collected by Martin O’Kane and John Morgan-Guy.

The travel section in the Aberystwyth library has 79 books on Wales. Many of the names are familiar: George Borrow, Peter Finch, Niall Griffiths, Mike Parker, Jim Perrin. Some are new like David Lloyd-Owen’s A Wilder Wales, (reviewed here 31st January 2018). All 79 offer their different routes into and across Wales. County-specific titles are common. Another new 2018 title A Year in Pembrokeshire joins the photography of David Wilson to a text by Jamie Owen. Gomer’s book on Pembrokeshire, marrying photographer Jeremy Moore with writer Trevor Fishlock, (reviewed September 12th2016), is the more alluring of the two.

Some of the 79 are slim like Walks from the Welsh Highland Railway or the series from Kittiwake Books. Another title that dates from 2010 is far from slim and is stored on the shelf for large books. It is a book of weight and substance, nine by eleven inches in format and even in paperback comes in at over a kilogram. Its origin is an AHRC project Imaging the Bible in Wales, hosted by the then University of Wales, Lampeter. The authors are 17 scholars from Wales, Scotland, Ireland, the USA, their fields the visual arts, theology and biblical studies. They would be surprised to find their work revisited in a summer article on travel.

Nonetheless, the book with its three hundred and ninety-eight illustrations is not just history and exegesis of tradition but a gateway into a wealth of public art of Wales. A few, like Epstein’s Majesties in Llandaff Cathedral, are familiar but the larger part of the works is lesser-known.

Every corner of Wales is represented. The essay “Setting the Scene”, by editor John Morgan-Guy, visits Pontargothi in Carmarthenshire, Pentrobyn in Flintshire, Llanfair Cilgedin in Monmouthshire and Monkton Priory in Pembrokeshire. The media encompass needlework, glass, engraving, oil and watercolour. The most affecting is the profile figure painted by Joan Fulleylove for the Reredos of Holy Cross Church in Robeston Wathen, Pembrokeshire.

The geography of Wales itself has a biblical stamp. Nebo on the Lampeter to Llanrhystud road is one of several and it is the same with Bethesda and Bethel. There is a Caesarea and a Golan close to Porthmadog. Much of the art in the book comes from distinguished names. Jonah Jones adopted Catholicism as an inspiration for his life work. Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan alights on Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ Annunciation of 2004 and Claudia Williams’ Madonna and Child of 1983 as examples of artists choosing biblical narrative for the subject matter. John Selway in his fourteen Stations of the Cross in Abertillery has, she says, politics rather than faith for its motivation.

The converse is that a secular subject may convey religious meaning. Lloyd-Morgan chooses Josef Herman’s Mother and Child of 1944-47. Cliff McLucas is represented by two banners in batik from 1988. They were commissioned by Brith Gof to mark the quatercentenary of William Morgan’s translation of the Bible.

Hannah Dentinger traces the evolution of the style and work of David Jones. His secular subject matter, a 1929 wood engraving from the series of the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, has clear roots in religious imagery. Nicola Gordon Bowe applauds the stained glass of the Harry Clarke Studios and, in particular, the artistry of Wilhelmina Geddes. Her rose window Te Deum for the cathedral of Saint Martin in Ypres is shown next to the west window for St Peter’s in Lampeter. John Petts’ window Doors of the Arc for the synagogue in Brighton and Hove is illustrated, a commission won after the work for the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The stained glass of Petts is given a chapter of its own by Alison Smith from Tate Britain.

The authors move across centuries of history of art in Wales. Oliver Fairclough in Biblical Imagery in Public and Private Spaces 1850-1830 recalls that the Davies of Gregynog would greet their guests next to a statue of Rodin’s naked Eve. Other writers focus on particular genres or artists. Larry J Kreitzer follows images of Paul across bronze, woodcarving and watercolour but mainly in stained glass in a dozen venues from Newport to Bangor. Andreas Andreopoulos looks at the orthodox church of St Nicholas in Cardiff. Sharman Kadish from Manchester University writes on the Jewish Presence in Wales: Image and Material Reality. The plainness of Pontypridd’s synagogue is a contrast with the domed or gothic grandeur of those at Merthyr and Cardiff.

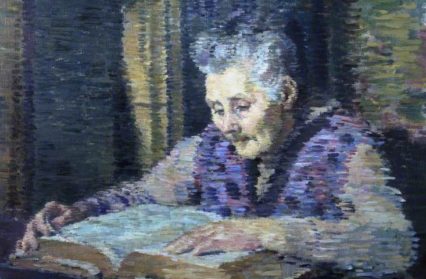

In the wealth of illustrations, there are a few favourites. A Memento Mori on St Issui’s at Partrishow has a skeleton, painted on plaster, with a spade dangling from a forearm. William Morris and Company is responsible for the greatest of Llandaff’s windows. Byrne-Jones’ the Nativity at St Deiniol’s in Hawarden is given a full glorious page. The Descent from the Cross is given a moving re-depiction in 1917 by Evan Walters. A full-page is given to Evan Walters’ Portrait of his Mother Reading the Bible twenty years later. His maturing style of brushwork depicts the curtains behind his figure in fifteen lines of the shimmering parallel pattern. A greater contrast could not be had with Blair Hughes-Stanton’s startlingly sensual engravings from the Revelations of St John. John Petts brings asymmetry of elegance to his window Peace, Be Still in St Mary’s Church, Fishguard.

Before I read this book of weight Gorseinon was the town with the 3M water tower and an Arthur Llewellyn Jenkins furniture showroom. Now it is also the location of the Blessed Sacrament Church with sculpture by John Petts. Llanfair y Bryn just outside Llandovery is home to lustrous windows by the same artist. The scope is huge but still not quite complete. That treasure of the Upper Dee Valley, Langar, escapes attention. But Biblical Art in Wales does for the reader what all good books do. It changes the way of seeing the world.

Biblical Art from Wales is available now.

Adam Somerset contributes to Wales Arts Review regularly.