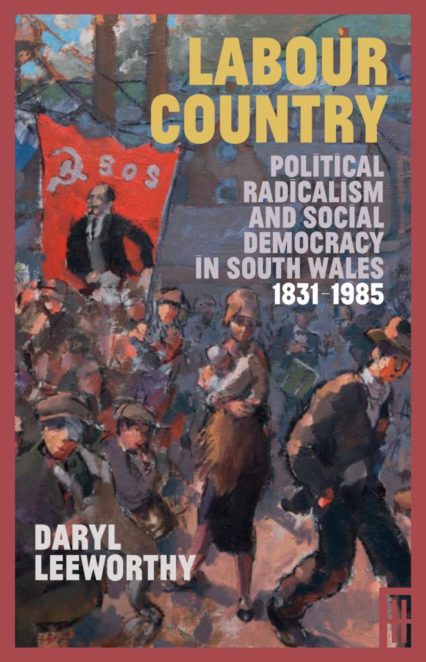

Nye Davies cast a critical eye over the latest non-fiction release from Parthian, Daryl Leeworthy’s history of the Labour Party in Wales in Labour Country.

The Brexit vote in Wales has shifted the debate in Welsh political discourse. Given the popular picture of Wales that is often painted of a progressive country with proud traditions of socialism and community collectivism, the Brexit vote may seem surprising. Then again, the warning signs have existed for a while: Gwyn Alf Williams wrote of Wales becoming a right-wing country as far back as the 1980s. A lot of soul-searching has been taking place in Wales to try and work out why the Brexit vote happened and why Wales turned its back on the European Union.

In an attempt to recapture this picture of radical Wales, Labour Country documents the proliferation of community groups and friendly societies and the rise of the Labour movement in South Wales (emphasis is placed on the capital ‘S’), from its early beginnings throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. The period of 1831-1985 covers what Leeworthy sees as the rise and fall of social democracy in South Wales.

The argument of the book is clear: there once existed in (South) Wales a radical social democracy, markedly different from the rest of Britain, which characterised the communities of industrial South Wales and shaped the institutions which emerged from these communities. Leeworthy argues that there has been a departure from this radical social democracy, a departure which culminated in the defeat of the Miners’ Strike in 1985. He claims that Welsh Labour’s response has been too heavily focused on soft-nationalism and has simply invoked the memory of a radical past without encouraging the development of a tangible social democracy. Leeworthy argues that to improve the lives of people in South Wales, the vitality and fuel of South Wales culture needs to be recaptured and needs to replace the purely rhetorical references to Wales’ radical past.

Labour Country documents the emergence of co-operative politics in South Wales from the 1830s onwards. It details the developing radicalism of South Wales which coincided with the demand for political representation and the challenge to liberal hegemony arising from the assertion of the rights of labour. The book takes us through the development of the trade unions and the emergence of new groups such as the Social Democratic Federation, the Independent Labour Party and the South Wales Miners’ Federation which were to have a major influence in shaping the political culture of South Wales. Socialism was becoming akin to a religion in industrial South Wales.

Leeworthy then takes us through the development of radical politics in South Wales to the Labour Party becoming a dominant electoral force. The Labour Party, he argues, became the dominant force in South Wales politics. It adopted a middle ground: “pragmatic, plural, reflexive, rather than utopian, absolute or revolutionary”. By finding a middle ground and prioritising “the ballot box and the institutional framework of democratic government” the Labour Party was able to “translate radical political ideas such as Noah Ablett’s industrial unionism into social democratic action”. Labour in Wales became a triumvirate of election winning, activism and industrial force.

The high point of ‘radical pragmatism’ was from the 1930s up to the time of the 1945 Labour government when the Labour Party became the national party of Wales and South Wales became what Leeworthy describes as “Labour’s citadel”. Leeworthy praises the achievements of the Labour government, with South Wales politicians Aneurin Bevan and James Griffiths fundamental to it. These figures are highlighted as being representative of the radical pragmatism of South Wales, as they were able to combine radical principles with practical politics.

The departure from ‘Labour Country’ is attributed to the disappearance of Labour’s industrial base that it relied on so heavily and which has not been replaced. It was the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 which Leeworthy pinpoints as marking the collapse of radical social democracy in South Wales. He argues that the strike did not signal the rekindling of community spirit: ultimately the strike was a failure and represented the lack of available response to Thatcherism and deindustrialisation. The effects of this period are still being felt in Wales today.

The result of this departure from ‘Labour Country’ was the replacement of radical social democratic politics by soft-nationalism and nostalgic invocations of Wales’ radical past. Leeworthy gives ‘Clear Red Water’ as an example of such nostalgia, arguing that content-wise it has been valueless because devolution has not re-created the social democracy that previously existed in South Wales. He bemoans the lack of emphasis on South Wales culture and argues that that South Wales with a capital ‘S’ has been lost in attempts by revisionist histories to talk about constitutionalism, nationhood and identity.

The strengths of Labour Country lie in the piecing together the stories of the various groups and organisations which existed and thrived in the development of industrial South Wales. Extensively researched, the passion for the subject is plain to see. The minutes of meetings, the tales of fascinating characters, newspaper articles on local events, the vast amount of evidence is brought together to build a narrative which brings the history of this period to life and emphasises the vitality of community politics in South Wales. The breadth of research into the different groups is wide and Leeworthy does an impressive job of showcasing the distinct communities of South Wales, with equal weight being given to their unique experiences.

Despite this, Labour Country often lacks a critical edge. The numerous references to the politics of ‘radical pragmatism’ highlight this. Alternatives to ‘radical pragmatism’ are often dismissed as “utopian” or “grievance” politics. Surely it must be contended that ‘radical pragmatism’ has not led to a radical transformation of society. It has been unable to defend Wales from the weight of Thatcherism and global shifts in the economy. Dismissing any alternative to ‘radical pragmatism’ as Leeworthy does prevents us from developing a critical analysis of it as a strategy to achieve change and critically reflect on the politics of the past. One only needs to read the work of Miliband, Nairn et al. to see the flaws of the ideology of ‘labourism’ and its reverence for parliamentary institutions.

Contrast this with the work of Gwyn Alf Williams who also argued that there existed in industrial South Wales (‘south’ Wales in Williams’ case) a radical tradition that was eventually lost, only to be replaced by a myth that was persistently played upon by the Labour Party. Yet Williams recognised the limits of Wales’ radicalism and, with great lucidity, exposed them. In When Was Wales, Gwyn Alf wrote that yes, Labour hegemony had been characterised by “a more humanitarian, civilized and educated society, by a genuine concern and an effective welfare state, by a genial and easy populism in style”, but it was also characterised “by accommodation snug within the system, with its political mechanisms becoming an arena for rivalry and agreement between pressure groups, its parliamentary representatives becoming more and more middle-class and professional and dependent on the support and manipulation of powerful trade union and locality controllers”. Arguing that the party only came alive during elections, he wrote that it was characterised by “the customary Welsh blend of high thoughts and low thinking, by widespread petty corruption and nepotism”.

It is this type of analysis which is missing from Labour Country. Rather than accepting outright the need to return to ‘radical pragmatism’, we should be examining its features more closely. Both Leeworthy and Williams argue that the industrial base which was the foundation of radical politics in Wales has been lost not to be replaced, but Williams engaged with a critique of the institutions which Labour in Wales was working within. We cannot adequately understand or learn from the past in Wales without first beginning to understand the intricacies of the British state and its place within the context of international capitalism.

Leeworthy argues that the path to devolution was the wrong solution to South Wales’ problems, twice noting that “it did not have to be this way”. He complains that too much academic focus has been on nationalism, constitutionalism and identity, to the detriment of the vitality of South Wales’ history. However, it could be argued that a much richer picture of the history of Wales can be gleaned by analysing a variety of issues and attempting to understand the rich diversity of experiences in Wales.

There is merit in Leeworthy’s call for a return to radical social democracy. He is right to point out that Labour in Wales has often played too heavily on the rhetoric surrounding the working-class history of South Wales without matching that rhetoric with radical practice. This needs to change as Wales is still suffering from the fallout from de-industrialisation. But this cannot be done without first recognising the limits of past ventures in radical social democracy. To develop a way forward we must fully explore the multiple and complex understandings of Wales as a nation, taking into account class, identity, institutions and everything that comes with them.

Labour Country by Daryl Leeworthy is available now from Parthian Books.

You might also like…

An adopted son of Newport, Ben Glover, looks at the radical political history of Wales’ third city and finds a story of rebellion, Chartism and democracy.