Looking Out by Peter Lord: Adam Somerset reviews a collection of six essays which traverse a 150 year history of Welsh art.

The marker between goodness and greatness in a critic or a historian is clear-cut. The great rattle the orthodox view. Challenge flows through their bloodstream. They do not need to be right in every detail but they prise open a new perspective.

Art is a place for combat; when it ceases to be so it withers. The most ringing cultural action of 2020 in the United Kingdom was the toppling of Edward Colston into the water of Bristol’s docks. In Denbigh, Henry Morton Stanley stands proud as a figurehead for Wales. The fact that he remains means that he enjoys a thumbs up from the political parties of Wales.

Peter Lord, a practising artist before pre-eminent art historian, learned early on that public art was a combustible area. He won a public commission. A part of it was made of a mosaic which entailed his working on hands and knees. For a while a citizen of Whitland would stand near to the artist’s hands and offer his daily suggestion of “why don’t you f*** off where you came from?”.

Peter Lord, a practising artist before pre-eminent art historian, learned early on that public art was a combustible area. He won a public commission. A part of it was made of a mosaic which entailed his working on hands and knees. For a while a citizen of Whitland would stand near to the artist’s hands and offer his daily suggestion of “why don’t you f*** off where you came from?”.

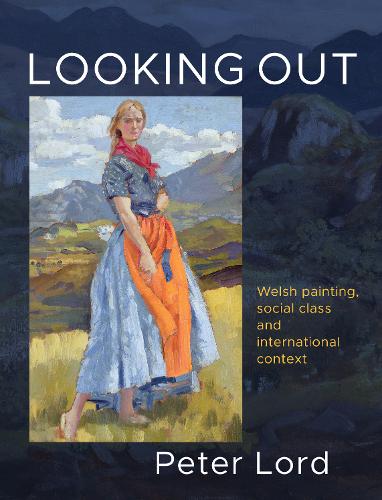

With Looking Out, a collection of six weighty essays, Peter Lord continues the thesis that has been his historiographical achievement. Wales has a visual tradition. Lord has his long-standing opponents, curators, critics and cultural appointees who have combined in the past to declare that Wales is a land of voice and word. In Lord’s perspective, culture is the story that a national community shapes to tell itself.

Looking Out adds new chapters to his significant recharting of the historical record. We learn that Evan Williams was more than a prolific creator of portraits and landscapes. He wrote four essays on aesthetics and the history of art, the first attempt ever made to present the subject in depth in the Welsh language. Peter Lord analyses his predicament, how to reconcile the superiority of his own age of faith with the artistic accomplishment of classical Greece.

The second essay follows the tripartite careers of Albin Roberts Burt, William Jones Chapman and John Cambrian Rowland. The essay on Edgar Herbert Thomas, with nineteen illustrations of the artist’s work, demonstrates Wales’ most skilled exemplar of the symbolist tradition.

The essay on Thomas Evelyn Scott-Ellis – a crucial figure also for the theatre of Wales – is bold on the psychology. “The fact that de Walden chose to express this ancient relationship between wealth and art in the context of Wales owed much to a sad and isolated childhood which engendered in him a deeply felt need to belong to a place and a people”.

While Henry Cyril Paget, 5th Marquess of Anglesey, plunged into making a strange art of his own, de Walden at Chirk Castle played the role of patron. “He benefited”, observes Lord, “from that symbiotic relationship which expressed the need of those who inherit great wealth to inject intellectual and moral sustenance into their lives by the purchase of the credibility that the presence among them of painters, writers and artists can bring”.

Ironically, after sponsoring a dramatic prize worth £100, he was not too comfortable with J O Francis’ Change. (The play for new readers has also been republished this season by the ever-eclectic Parthian.)

Critical writing is enlivened by the temper of critical personality. Lord has assaulted Clive Bell before. So Bell of Bloomsbury: “Only artists and educated people of extraordinary sensibility and some savages and children feel the significance of form so acutely that they know how things look”.

The subtitle of Looking Out is “Welsh painting, social class and international context”. Evan Williams was schooled at Clynnog Fawr and made his way to Bala Theological College. Clive Bell’s course went from Marlborough to Trinity, helped along by the family ownership of mines in Neath and Merthyr.

Lord, recalling his own route, notes caustically a “nasty but influential piece of literary snobbism called “Art” had thoroughly poisoned the mentality of those into whose company I was paradoxically directed.” Lord’s attention turns from form to the story of a painting. Each picture carries its own biography; by extension it is a part of the nation’s biography. But the nation’s biography is suffused with the views from visitors.

The dilettantism of visitors reaches a peak in the clustering around Harlech. Lord cites Robert Graves to the effect: “having no Welsh blood in us, we felt little temptation to learn Welsh, still less to pretend ourselves Welsh, but knew that country as a quite ungeographical region. Any stray sheep-farmers whom we met seemed intruders on our privacy”.

The weight of artists from outside leads Lord to suggest two categories of depiction. “Because of the presence in Wales of a high proportion of artists from outside the communities in which they worked the distinction between painting as observation and painting as experience has become fundamental to the understanding of representation in our narrative art”. This failure of experience is epitomised in Augustus John, his views described as a “beautiful but disingenuous re-hash of Wild Wales”.

A John view in the vicinity of Blaenau Ffestiniog is taken as an example. The territory as a real lived-in land is a place of quarries and several railways. But it is simply not noticed by the artist. “In the context of the arrogant and condescending attitudes made plain by John and his circle in their writings about the living communities of the place, the painter’s lack of interest in the dramatic human impact upon the landscape that he painted, so evident around him, seems to me a morally as well as intellectually stunted imagination”.

The moral emphasis is repeated with the verdict on M E Eldridge. “Accepting a request to create a public narrative carries a responsibility to do more than assemble a collection of disparate private fancies, however elegant the final construct in visual terms”.

The not-noticing of the reality of Wales is the bedrock of the view promulgated by curators and critics. “None of the portrait paintings of Evan Williams is famous. They have no place whatsoever in the narrative of international art history. But, as a consequence of the unchallenged acceptance in Wales of that narrative as the only and universal validation of art, neither are they celebrated or even accorded a visible place in the histories of the culture from which they emerged”.

Lord uses the word “contempt” and it comes with a consequence. It is “profoundly damaging to the nation’s self-esteem and confidence in its cultural identities”. Pungent cultural critics do not need to be right in every detail but their value is in prising open a new perspective. But he is correct in the lopsidedness of the curatorial view. There is no public honour for Evan Williams but there is honour for Henry Morton Stanley.

Looking Out, edited by Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan, is an invaluable addition to the critical conversation. Text and the 214 illustrations have been produced in Llandysul. The hand of Gomer is its ever-reliable hallmark for the quality and the pleasure to be had in the book’s physical finish.

Looking Out: Welsh Painting, Social Class and International Context by Peter Lord is available now from Parthian.