Richard Lewis Davies looks back at the entertainingly revealing election diaries of Plaid Cymru’s Mike Parker.

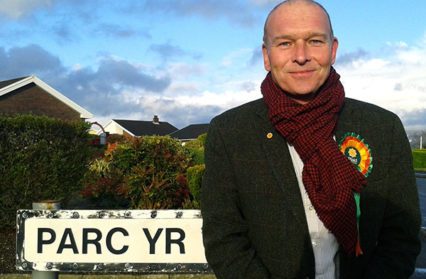

It is still dark on a Friday morning in early May 2015 when Mike Parker and his partner Peredur walk away from Aberaeron Leisure Centre. They are recovering from a night of waiting and then bearing the count of the Ceredigion constituency in the parliamentary elections. It is the end of two year battle for Parker to become the Plaid Cymru MP for the odd and challenging seat on the west coast of Wales. It is also somewhere along a personal and political journey that has taken him from Middle England Middle Income Kidderminster as schoolboy activist for the Liberal party with Conservative parents to a student infatuation with first Old then New Labour in London and then through writing and comedy to a cottage in the hills above Machynlleth, Welsh-speaking and fully committed to the fate of a small country on the edge of Europe. Mike and Peredur are both exhausted. There is from the spurned candidate an overwhelming sense of relief, that it is over, and perhaps when he looks back on it with this book, that he has survived.

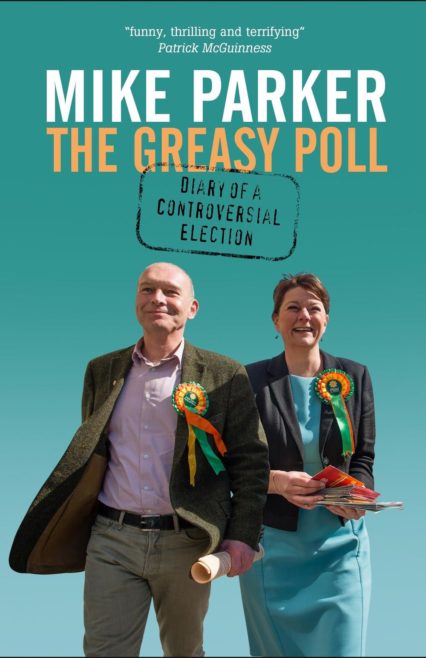

The Greasy Poll, a diary of election campaign over three years from the personal perspective of the candidate, is a fascinating account of the election process as it stands in the UK with particular focus on Wales. There is drama, political infighting, image consulting and ego-massaging just in the confines of the candidates own party, Plaid Cymru. Once the election gets going properly everyone else weighs in, from the hapless Labour Party, the devious Lib Dems, the hard-to-please Greens, the one-issue UKippers, and the largely absent Conservatives, campaigning from a distance.

The Greasy Poll, a diary of election campaign over three years from the personal perspective of the candidate, is a fascinating account of the election process as it stands in the UK with particular focus on Wales. There is drama, political infighting, image consulting and ego-massaging just in the confines of the candidates own party, Plaid Cymru. Once the election gets going properly everyone else weighs in, from the hapless Labour Party, the devious Lib Dems, the hard-to-please Greens, the one-issue UKippers, and the largely absent Conservatives, campaigning from a distance.

Ceredigion in all its charm, independence, and downright oddness, is laid bare: the back-to-the-landers; the one-issue-and-the-issue-is-the-language activists; the White flighters who left the Midlands because there were too many black people there and are now complaining about the Poles in Aberystwyth; the farmers complaining about Europe while taking thousands in grant support; the badger cullers; the badger lovers; the frustrated academics wanting more money; the local councillors worried about constituency boundary changes; the students worried about the world, and the drone scientists. As a prospective candidate you are obviously fair game for everyone with a grievance and pot to stir but remarkably through all this Mike Parker comes across as someone who genuinely likes people.

Reading the book immediately in the light of the debacle of the Europe Referendum is illuminating in that Parker identifies a year prior many of the issues that would resurface a year later, and this time will be embraced by a large electorate ignoring the mainstream political advice and wrecking the establishment consensus in the process. True to form Ceredigion did go its own way, voting to Remain; but despite that Parker was on the money a long time before most commentators. In fact, to some extent, a long way ahead.

I remember his articles in 2001 for Planet Magazine where he outlined an argument that west Wales was becoming a home for Final Solution fundamentalists. The British National Party leader, Nick Griffin, had recently moved to Wales and they were getting some success in local council elections. I thought at the time he’d overstated the case based on some of his conversations down the local pub with a few village oddballs who wanted to give him the benefit of the their opinion. I’d moved to south Ceredigion at about the same time and got a completely different perspective, the people were largely liberal, open and outward-looking. A decade and a half along and at the end of a long election campaign he does make the point it is more complicated than it first seemed.

The incomer debate was an issue that flared during the campaign when some of his earlier articles, now fifteen years old, were seized upon by Chris Betteley, a journalist at the Cambrian News which led to headlines such as “Plaid Cymru candidate says all incomers are ‘Nazis’”. The inverted commas added by the editor of the News because Parker had never actually said such a thing. It’s amazing what you can get away with in the press and on social media during an election campaign. It starts with lies and moves onto to racial smears, religious bigotry, incitement to violence – mostly in west Wales it was just lies.

The row created an uncomfortable few weeks in the centre of the campaign for Parker as a social media storm of unsubstantiated smears, gleefully stoked by his rivals threatened to consume his candidacy. There were inevitable calls for his resignation (politicians seem to love doing this) and for his apology. The Labour candidate weighs in heartily on social media until he is forced into rapid retreat when his exhumed juvenile exhortations on the same social media (to pour Tipp-Ex on the cars of English supporters displaying a St George’s Flag during a football tournament) sentence him to a few days in the Twitter stocks. Mike Parker, to his credit, despite some tepid support from his own party team, refuses to apologise for his writing and thoughts on the issue. He also refuses take out an advert in the Cambrian News defending his position despite party pressure to do so. The paper quickly capitulates under threat of action from the Independent Press Standards Commission and offers him a right of reply which they print on page 6. The “NAZI” claim was a front page banner. It does hurt his campaign but not, at this distance, his integrity.

In the end the election is a failure for Plaid, in Ceredigion and in Wales as a whole. Despite a national flight from the Liberals, a popular constituency MP in Mark Williams is returned to Westminster and Mike Parker, despite his best efforts to engage across a wider constituency of voters for his party, fails to increase the share of the vote of the previous challenger, the underwhelming Penri James. The contrariness of Ceredigion triumphs again, the people who appear to change sides vote Conservative, Green, Labour and forebodingly in most numbers, UKIP. Parker was never going to persuade people to come to his side. The Plaid vote falls. It is a shattering personal blow.

Aside from the analysis, personal and political, of interesting times, this is a valuable and insightful book about the Welsh condition. Mike Parker is honest and endearing as a guide to Welsh politics. He isn’t afraid to open up about his ambitions, mistakes and the double-speak which he fears being consumed by. He is wonderfully honest about Plaid Cymru, the leadership of Leanne Wood, the thwarted ambition and pomposity of its one elder statesman in Dafydd Elis Thomas and there are revealing cameos from other “stars” in the Welsh Nationalist political firmament, notably Elin Jones and Cynog Dafis. Parker is occasionally delightfully funny for an aspiring politician. At an LGBT event in Aberystwyth he banters with the crowd from Tregaron, recalling a quote from an interview with a resident along the lines of all you need to know about Tregaron is that “Everyone Fucks Everyone Else.” The Tregaron contingent love it. From a personal perspective it confirms he has always been a liberal and a socialist and someone committed to the rights of minorities and in getting people’s voices heard. He could have stood for a number of parties at different times with these credentials. His bid to represent Ceredigion was a genuine and heartfelt one. It is a loss to politics that he wasn’t elected. Perhaps he will try again but I doubt it. After reading his book he’d get my vote.

Richard Lewis Davies was a committed floating voter in Ceredigion from 2003 to 2014