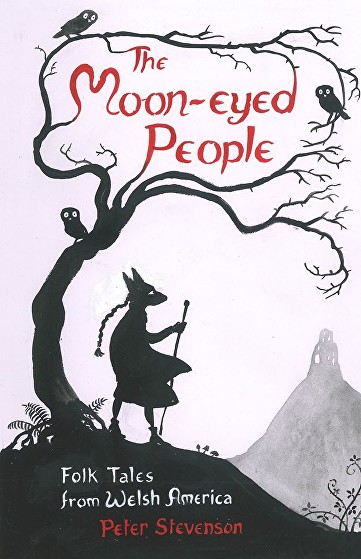

Thomas Tyrrell reads and reviews Peter Stevenson’s The Moon-Eyed People, an intriguing collection of folk tales from Welsh America.

Folk story collections have usually been national affairs, even since the Brothers Grimm kicked off the trend way back in 1812 with their collection of Germanic folk tales. There’s something genuinely intriguing and transgressive in Peter Stevenson’s collection of Welsh-American folk stories, with the potential to show us how stories cross borders, and how different narrative spring out of the same primordial source. There’s also a certain amount of risk: in these sensitive times, you could be hit with charges of appropriation from both sides of the fence.

Coming to The Moon-Eyed People from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, another change stands out. The classic stories in Grimm have a minimalist simplicity, shaped and smoothed by thousands of tale spinners. They begin at the beginning, come to the end, and stop. The stories in the Moon-Eyed People reminded me more of the parts of the Arabian Nights where one story keeps getting interrupted by another. I found myself wondering, at times, how much stuff you can cram into one narrative before the seams start to pop. Here’s a sample paragraph from the middle of the book:

I finished my travels in Pennsylvania in a small town not far from Pittsburgh, where Andy Warhol was born. There is a huge multi-storey gallery of his work, where the staff are easily mistaken for exhibits. Outside, there are statues of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team. The Welsh came here in droves. One was a dyn hybys, a cunning man, John D. ‘Bonesetter’ Rees, who manipulated the torn and strained muscles of the miners and steelworkers, for if they were off work injured, they didn’t get paid. Rees’s reputation led him to become the first chiropractor to the Pittsburgh Pirates. There is a statue to him in Youngstown, Ohio, and his nickname was adopted by the most famous of bonesetters, Dr Leonard ‘Bones’ McCoy of the Starship Enterprise.

There’s a kind of magpie acquisitiveness to this paragraph that’s typical of the book as a whole. The introduction, for instance, is a rattlebag of historical titbits, personal anecdotes and feminist readings of the Mabinogion, fascinating in isolation but never quite cohering into a thesis. The first story, Wolf Girl Comes to Wales, suffers the worst from this habit, as the piling on of one werewolf story on top of another becomes wearisome and confusing. It’s also, relatedly, the only chapter of the book to be entirely fictional. The second (and titular) story, The Moon-Eyed People is more successful, combining the folk story of a woman who married the moon with the real-life story of a Cherokee woman. The transition jars, however, and the Welsh feel shoehorned in; the engaging tit-bit that the native tribes referred to the mining Welshmen they encountered as the moon-eyed people comes and goes mid-paragraph, and doesn’t really deserve to be the title of the story.

The non-fiction content builds as the book continues: we have retellings of Buffalo Bill’s visit to Aberystwyth, and a Welsh visit by Curley Humphreys, the FBI’s Public Enemy Number One in the decades after Capone. The quality also improves, and Stevenson is happier in the chapters that deal with storytellers themselves, giving us colourful autobiographical details of Iolo Morganwg and Wirt Sikes before retelling some of the folk tales they invented or collected. Part of the charm of the book is in the illustrations which make great use of colour, stay just the right side of spooky and heighten the enjoyment of every story. After the last chapter finishes, a full and frank bibliography acknowledges every debt and wards off any charges of appropriation.

The Moon-Eyed People is not what I was expecting. It’s like listening to an enthusiastic, knowledgeable person talking at ninety miles an hour. You learn a lot of interesting things, but you also begin to wonder how we got from there to here, and what West Virginia’s Mothman and Devil’s Bridge in Ceredigion have in common. The structuring and transitions in Stevenson’s work could have used work, but the charm of the book and the enthusiasm of the writing pull it through. It’s a bit of a mixed bag, but perhaps that’s appropriate for its subject matter: as the author’s sister says at the end of one chapter, “We are all mutts.”

Thomas Tyrrell has a PhD in English Literature from Cardiff University and is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.