Notes of Solidarity is a new daily series of mini-essays, poems, and reflections on the Russian war on Ukraine by some of Wales’s leading literary figures. Here, political philosopher, critical theorist and writer Professor Brad Evans draws attention to two classical artworks from Illya Repin and Kazimir Malevich which prove that creativity always finds a way, even in oppressive states.

The Cold winds from Siberia are blowing again. The war against the virus not so much ended but displaced by a familiar older enemy. Once the peoples of Wales looked East with comradeship and pride. But we soon learned to replace solidarity with the words of Solzhenitsyn. Europe’s gas chambers sisterly embraced by the bitter love of the gulag and its policy of equalisation. I recall once again the red flag flying on the mountains of Merthyr. Not like this. Never like this.

My attention is drawn to two classical artworks that defined the region. Creativity always managed to find a way, even in the most oppressive of states. Everything is in the eyes of the beholder. Have we not witnessed too much violence? Illya Repin’s Ivan the Terrible returns with devasting resonance. The tyrant and his murdered son, the Tsar whose anger killed the one he loved. Ivan’s eyes are filled with torment, anguish, delusion, and pain. They speak to a past, but also a deranged future that awaits. Nobody has quite captured that moment of madness better than Repin. But how many Ivan’s have we looked upon and continue to fall into their suffocating embrace? Oligarchs, pit owners, imperial monsters, and legitimised thieves, they all eventually kill what is within their closest possession, thereby killing the future as it might have been.

Europe has resumed slaughtering its sons. The spectre of Ivan has returned. Some are deeply pained by this reality. Others turn away from the terrible sight. Who can after-all stare at Repin’s work and not be traumatised by its horror? The shadow it casts offers no escape. And who can gaze into his eyes and not fall into the madding abyss? What have we done? What will we continue to do? Others still have their own agendas in play, reminding us of others, reminding us of them. But there’s are profits to be made. A tragic inevitability in a world in which suffering has become a competition. Yes. White men can be victims too. The Angel of History hasn’t afforded many in the million no such privilege.

I recall further the artworks appearance in dramatized spectacle Chernobyl. A series that narrated the historical bonds connecting these two nations in tragedy. Disposable miners once again would become the subterranean forgotten heroes. And the disaster would be instrumental in collapsing communism from within. I was 12 years old, and we were told for a while not to go out into the rain. Toxic clouds might be forming above. Still, it fell, and our own drenched fates persisted. Besides its always raining in the mountains of the valley’s minds. But today soldiers are returning to march over those contaminated grounds. Occupying what should be unoccupiable. Colonising their own fallout, which previously reminded us just how fragile borders really were to the merciless winds of change. Yet who or what is the source of the real contamination is difficult to tell. Maybe it’s just the violence? Maybe it’s just the violence?

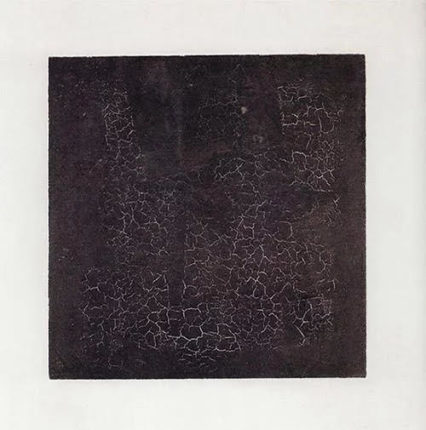

So, I look for a deeper perspective. Exploding towers simply remind us it’s just more of the same. Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square provides the ultimate testimony, the final witnessing. It’s all about the blackness of the void. Nothing is objective here. What it shows in fact is the perfect crime, the destruction of humanity and the very idea of a freely expressing artistic sensibility that might just have saved us. But this is also a reflection of what was to come. A Malevichean mirror of absence foretold. But this is not just a screen. The black here is cracked like a wounded earth. Scorched and devastated. Its depth reveals the end point of all destruction, nothingness complete. Maybe it is the pupil that centres the tormented delusion of the tyrant’s eye? Or maybe it’s the final cataclysm too often reflected back upon the disposable of history?

For more information on the Russia-Ukraine war, including ways you can help, please click here.

You can follow all contributions to Notes of Solidarity from Wales Arts Review here.