Wales Arts Review continues their celebration of Parthian’s Seventy Years of Struggle and Achievement: Life Stories of Ethnic Minority Women Living in Wales with an essay from special needs dentist, priestess and storyteller Chandrika Joshi who writes on coming to Wales as a refugee in childhood and her spiritual journey as a priestess.

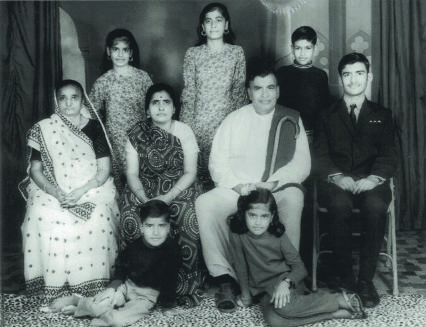

I was born in a small village in Uganda called Iganga. My father was a Hindu priest and my mother was a homemaker, and we were a close family of six siblings living in a small house. My parents were middle class and did relatively well, so life was very secure and there wasn’t a struggle for money, which was significant because education was not free. Fortunately, all of us excelled in our studies, particularly my older brother and sister.

I remember it always being sunny in the village, with rope swings hanging from beautiful mango trees. You could go running around barefoot, exploring everything from the forest – which was at the edge of the village – to the school where you could pick jasmine flowers and watch the vast variety of butterflies. I was very creative and used to love painting, drawing, writing and dancing. I also had a thread of spirituality from a young age and wanted to explore God, and questioned my parents about the philosophies around Hinduism.

Life changed for me when my father had a massive stroke in his 40s, which created an incredible upheaval in our lives. My mother moved into the hospital, which was in another town called Jinja, to help take care of my father, and took my six month old baby brother with her. Five of us were left at home under the care of my twelve year old brother, Pankaj, and my ten year old sister took care of my two year old sister. I was seven at the time. Although the neighbours helped, it was a traumatic experience, and all my siblings and I were seared by this event in our lives.

My father was in a coma for the first week but woke up later with my amazing mother by his side. The right side of his body was paralysed and he couldn’t move his limbs on that side. There were no physiotherapists, but as my mother was told that physiotherapy was the only hope, she exercised my father’s limbs all day long while nursing a baby in tow. When my father was discharged, my mother, with the help of a neighbour’s son, continued the physiotherapy at home until he was eventually able to walk. She also cut down the salt in his food, which he was unhappy about because he loved his food, but she tolerated his frustrations until he got used to the new diet. Once my father could walk again, he would go for miles and miles every day to maintain good health.

Uganda was a country with no social service support, so if you didn’t earn money, you would starve. With my father being unwell, there was no income coming in, so my mother and older brother started learning from my father and conducting some parts of the priestly services. When my father was better, my mother returned to being a homemaker, and my father resumed working with the help of my older brother, Pankaj, whose life totally changed. At the age of twelve, he went from being a child to an adult in a flash. My siblings and I were in awe of Pankaj for what he did for our family and us.

I was fourteen when we had to leave Uganda. In August 1972, Idi Amin announced that he wanted Ugandan Asians with British passports to leave the country within three months. The whole fabric of society that we knew began to unravel and Uganda was totally turned upside down. Everyone was fending for themselves, and my father felt vulnerable because of his disability and didn’t know what to do. He didn’t want to split the family and, as my brother was already in the UK doing his A-levels, he decided we should come here.

Logistically, it was very difficult to leave, and when my father managed to get plane tickets, we had less than 24 hours to pack our bags and leave. The journey was very difficult and especially traumatic, and we were relieved when we finally managed to get our seats on the plane. We landed in Heathrow in October, freezing in our summer clothes. A charity met us coming off the plane and gave us warm clothes and took us to a massive refugee camp at Tonfanau Army Barracks in north Wales. I remember leaving the train station and being in this wilderness in the rain, with sheep climbing the hills and the smell of salt and seaweed in the air.

We were at the refugee camp for four months, where my sister sat her O-level exams and I went to the local school in Tywyn. Life in the camp was stressful because I came from a small, conservative village and felt exposed in this unstable environment. We also lost our family stability because my mother suddenly became very ill with a heart infection. She was taken to a hospital in Machynlleth. It was difficult for any of us to visit her, and my mother, being so isolated and worried about us, had a nervous breakdown.

In February 1973, my family was finally given a little council estate house in a village called Penrhys in the Rhondda, and my mother came home a week later. The Rhondda people were lovely—very friendly and nosy, which is very helpful for refugees, especially my father, who was disabled and my mum with her poor heart. There were ten refugee families in a similar situation to us who were housed in the Rhondda in different villages, so we started mingling with them. I can understand how minority groups in this country stick to their culture more strongly than in their homeland, because you want so much not to erase who you are and where you come from.

I went through a journey over the next four or five years that was really difficult for me on a personal level, trying to fit in and arguing with my parents all the time. I passed thirteen O-levels but totally failed my A-levels. In retrospect, I was probably suffering from depression, feeling lonely and isolated. I applied to do radiotherapy in Middlesex Hospital in London, going from a little village to central London with my social-phobia and lack of self confidence was a challenge. I had to resit my physics exam, and they decided to kick me out of the course, saying I wasn’t bright enough for radiography.

I came to Cardiff and couldn’t find anything to do because I was considered too bright for certain things and not bright enough for others, and there was no middle ground for me. Finally, I got onto a new course started by the Welsh Office called Physiological Measurements, and that’s when I vowed that I would prove to myself that I could do anything I put my mind to. I was lucky I had a mentor called Carol Jones, who believed in me and encouraged me to fly high. She was like a fairy godmother or guardian angel, and everyone needs that.

I started studying really hard right from the beginning and got distinctions in every exam I sat, and was awarded a prize by the Welsh Office. I wanted to go to university, and I applied to do dentistry, thinking I might not be bright enough for medicine. However, dentistry has been a fantastic career for me. I work as a specialist in special care dentistry two days a week. I work only with special needs patients— people with various impairments—mental, physical or medical, meaning that they can’t access the general dental service.

Another avenue I’ve pursued is as a Hindu priestess. Once my father resumed working as a priest, he used to take one of the children with him to help. It was usually my older brother who went with him, but we younger ones also had a chance, and it was such an honour to be by his side learning and listening. I would sit by him, always very nervous because my father was very strict, very methodical, and a perfectionist.

In 2002, a young man I knew from Uganda was getting married to an English girl. My father had conducted the marriage of his parents and he wanted someone from our family to do his wedding, and I offered to do it. I sat down and started learning the service, and my first wedding was in Leicester, with 600 people. My brother was concerned that those in Hindu society would be hostile towards me for taking on a role that is normally reserved for men. In fact, it was the opposite, and I had really good feedback. All the young ones ran up to me afterwards and said, ‘We’ve never seen a woman priest.’ I had so much positivity, and that was the start of becoming a Hindu priestess. Being a priestess has helped me with my own spiritual journey. I’ve moved away from the ritualistic Hinduism I grew up with and progressed to a more philosophical and experiential Hinduism.

My mother was a storyteller, as was her mother. When we were children and my father travelled all the time doing his priestly things, I remember we used to sit outside under the beautiful African sky full of stars as bright as lightbulbs. Sometimes children from the neighbourhood would join in and my mother would tell stories that she had heard from her mother. The stories were sometimes religious and other times they were fables and mythological tales, and often the protagonist of the tale was a strong woman.

I started telling stories at the Cardiff storytelling circle about eight years ago. I recently won a mentorship programme with the Beyond the Border Storytelling Festival, which has allowed me to transition from a casual teller of tales to a professional storyteller. I am currently working with Arts Council Wales as a creative practitioner, exploring the concept of multicultural Wales with schoolchildren. With that project on the go, I am now retiring from dentistry.

I feel that whatever is right for you happens, as life is a journey and not a destination. The universe gives you what you need, even if it does not give you what you want. What does not break you, makes you, and the thing to do is keep an open heart and accept what comes your way as a blessing.

Seventy Years of Struggle and Achievement is available via Parthian.