Elin Williams reviews Children of Mine, a theatre production which covers the tragedy of the destruction of Pantglas School in Aberfan.

Recounting a dense historical event through the theatre is an extremely delicate process. There can be conflict between historical fact and creative fabrication, but in order to render history through theatre, it is crucial to be able to create a narrative to interest and entertain. In order to successfully produce a piece of theatre which aims to tell an important story, these two elements must peacefully co-exist, and if they don’t, what is left is a bad piece of theatre which could potentially offend.

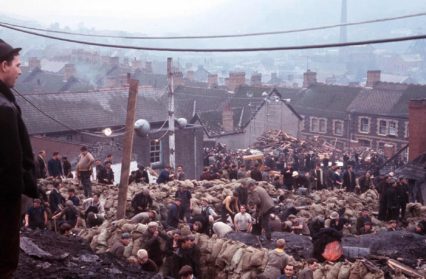

Mark Jermin’s production Children of Mine tells the horrific story of the destruction of Pantglas School, Aberfan after colliery debris suffocated the school in 1966, killing 116 children and 28 adults. The production has certainly faced its obstacles. Originally postponed in October 2012, it was reported that survivors of the tragedy were unhappy with the production, as they claimed they were not consulted on the historical accuracy of the event. However, the play is now going ahead and will be taken to the Edinburgh Fringe festival next month.

The nature of the disaster and, evidently, the concerns of survivors pose several complications, and striving to create an accurate, sensitive narrative must have been an almighty challenge. To create believable, fictional characters, especially when survivors will be able to testify whether they were plausible inhabitants of Aberfan in 1966, is crucial. On the whole, the production does its best to create these believable characters and recount the horrific events in a sensitive way, but certain modern influences and misunderstandings seem to restrict the production.

A group of nine up and coming Welsh actors make up the chorus of the piece. These actors must be commended for their skill and maturity at such a young age; the main problem seemed to lay more with the direction the actors received as opposed to their acting. It often slipped into the hysterical, which made the piece feel disjointed from the realistic reactions of parents in 1966. Interviews from parents who lost children in the disaster should have served as a creative backbone. What is evident from these original interviews is a composed, silent suffering. The hysterical grief conveyed in the production seemed to get a little out of hand.

This linked to another problem, which was the confusion over the sense of time. Slipping from heavy chunks of chorus story-telling to disproportionate snippets of dialogue, the piece really seemed to be in a temporal limbo. This could potentially be considered as symbolic of the sense of limbo which was felt by the community waiting for their children to be unearthed, but really it just meant the production felt fragmented. Costumes were modern, dialogue seemed fairly modern at times, and the use of a modern dance to ‘Ar Hyd Y nos’ dragged the whole event uncomfortably into the present. In order to have avoided this, the chorus pieces could have been reduced, as at times the actors were out of synch with each other. Alternatively, the whole thing could have been recounted through character dialogue as, although a modern perspective of the tragedy and its aftereffects is a good idea, the recounting of the aftermath of the disaster was extremely short-lived. In fact, it was essentially non-existent. One of the main advantages of telling a story from a future perspective is to explore what effect this event had on future generations, what effect it had on the coal mining industry, so to barely touch upon these issues was, quite frankly, a waste. It could have, therefore, done without the modern perspective at all, and thus avoided this jumping around in time.

The use of ladders as coal tips was very innovative. The cold, hard feel of the ladders towering over the small village of Aberfan was extremely effective. The ladders also served as useful devices to create different scenes. The production was undoubtedly very emotional, but in a way which didn’t feel completely connected to the event which it was trying to convey. An ambitious project, with some fantastic acting talent, Children of Mine struggled to reach its full potential as a sensitive re-telling of a tragic event which ruined many lives.

Children of Mine at RWCMD, Cardiff

Elin Williams has written a number of reviews for Wales Arts Review.