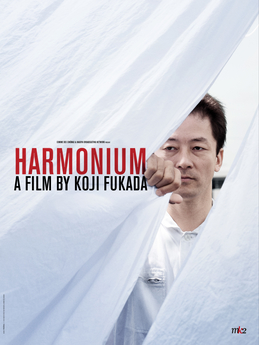

Fedor Tot takes a critical look at Harmonium by Koji Fukada, an intriguing and dramatic film certainly described best as a film of two halves.

Japanese cinema has a long tradition of middle-class social realism that goes all the way back to the post-war era with Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse, and Kenji Mizoguichi (with the prolific Hirokazu Kore-eda being its biggest contemporary proponent) and for two-thirds of its running time, Harmonium fits very comfortably into this movement. Japan’s tradition of cinematic social realism is probably one of its finest cultural exports and are a valuable resource for learning how the country has changed over the course of the past century – Portuguese director Pedro Costa once described Ozu’s work as being “the true Japanese documentaries”. Although writer/director Koji Fukada does showcase an understated visual style, and a good knack for observing daily life, Harmonium ultimately feels too beholden to its plot, which wraps in mysterious disappearances, bludgeoning symbolism, and contrivances aplenty in an attempt to set it apart from other works of the same milieu.

We enter the house of metalworker Toshio (Kanji Furutachi) and Akie (Mariko Tsutsui), who have a bright young daughter in Hotaru (Momone Shinokawa). The family live out a contented, albeit mundane life: they are the stereotype of many middle-income, middle-class families in Japan. One day, Yasaka (Tadanobu Asano), an old friend of Toshio’s recently out of prison, turns up offering to help in Toshio’s workshop in return for food and board. Toshio accepts without discussing it with his wife, a strange decision in the first place, and it appears as if Toshio is in debt to Yasaka, who admits to Akie that he committed a murder with an accomplice whom he doesn’t name. A devout Christian, Akie is initially shocked, but finds herself fascinated with the mysterious Yasaka, the two verging on the cusp of an affair before Yasaka oversteps his boundaries and his advances are rejected.

We enter the house of metalworker Toshio (Kanji Furutachi) and Akie (Mariko Tsutsui), who have a bright young daughter in Hotaru (Momone Shinokawa). The family live out a contented, albeit mundane life: they are the stereotype of many middle-income, middle-class families in Japan. One day, Yasaka (Tadanobu Asano), an old friend of Toshio’s recently out of prison, turns up offering to help in Toshio’s workshop in return for food and board. Toshio accepts without discussing it with his wife, a strange decision in the first place, and it appears as if Toshio is in debt to Yasaka, who admits to Akie that he committed a murder with an accomplice whom he doesn’t name. A devout Christian, Akie is initially shocked, but finds herself fascinated with the mysterious Yasaka, the two verging on the cusp of an affair before Yasaka oversteps his boundaries and his advances are rejected.

This portion of the film, taking up the majority of the first half of its 118 minute run-time, is quite excellent. An air of intrigue envelops Yasaka, a man of few words but an imposing presence, always dressed in the same white shirt; Asano’s performance is spot-on. Koji Fukada has an excellent sense of blocking and framing his characters too; he repeats the image of the family eating at the dinner table throughout, each time re-arranging an aspect to suggest a shift in emotional tenor. The claustrophobic sense of a potentially malicious character invading the sanctum of a family home is also reinforced in the frequent use of slow, barely perceptible zooms in long scenes, prodding at our sense of intrigue and discomfort with Yasaka’s presence.

At around the midway point, after Akie’s rejection of his advances, Yasaka severely harms Hotaru offscreen, after which Harmonium flashes forward eight years. Hotaru is now immobile and developmentally disabled and her parents are still desperately searching for Yasaka, who has completely disappeared. At this point, Harmonium starts layering on the contrivances and melodrama.

Instead of placing the characters into a traumatic situation and using their responses to generate the drama and narrative thrust of the film, Fukuda starts having them jump through narrative hoops to force them into a ham-fisted resolution that includes baptism symbolism, the cleansing of sin, and the guilt of the father being passed onto the offspring. Forget the initial hour of carefully calibrated mystery and unease, just sit back and enjoy a film undo all its hard work in the last twenty minutes.

It cheapens the sense of drama inherent in the story of how a family can survive an experience as devastating as having your sole child become entirely immobile and unable to live without care for her entire life. That would make for an exquisite film. What we have instead, in the end at least, is a tawdry melodrama that misses the woods for the trees, firing out at a half-cooked mystery instead of a taut family-based drama. Truly it is a shame, because for the most part, Harmonium is a pleasure to watch, a drama rife with intrigue and subtle direction. It has enough of a ‘genre’ element in its central mystery to ensure its narrative has a natural forward progression, but in the end it is squandered.

Harmonium is showing at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff from June 30th.

Fedor Tot is a Newport-based independent film critic and writer.