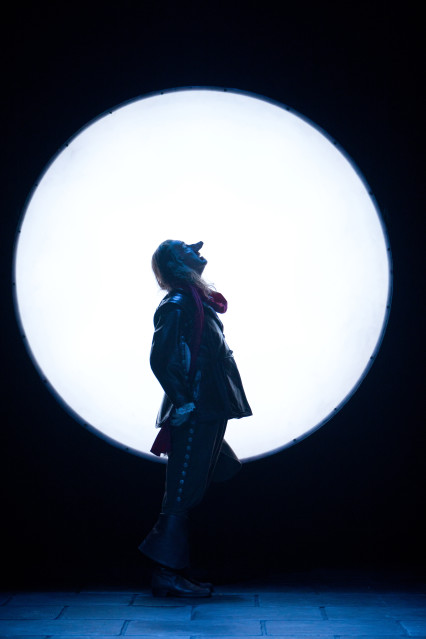

Theatr Clwyd have created a new take on the classic Edmund Rostand tale Cyrano de Bergerac, for the first time using an all-Welsh company to reinterpret this French classic, using translation by Anthony Burgess, it also features new Welsh language poetry by Twm Morys.

Twm Morys is a poet and harpist who also writes for television and radio, as well as lyrics, which he sings with his folk-rock group, Bob Delyn a’r Ebillion. In addition to three volumes of poetry (Ofn fy Het, 1995; Eldorado, 1999, 2, 2002), he has collaborated with Jan Morris on the two volumes, Wales, the First Place (Random House, 1982) and A Machynlleth Triad/Triawd Machynlleth (Penguin, 2004). Ein Llyw Cyntaf (Gomer, 2001) is his Welsh adaptation of Morris’s novel Our First Leader. This production, however, marks his first collaboration with a theatre company. Artistic director of Theatr Clwyd, Tamara Harvey has said of the production; ‘It’s also a great privilege to have additional poetry from acclaimed poet and musician Twm Morys, which, spoken in the Welsh language, will provide a new dimension to this classic play.’

Here Twm discusses with Emily Garside his previous experience with theatre, the influences on his work, the influences shaping this collaboration and his long standing relationship with the text that feeds this collaboration.

Emily Garside: Theatr Clwyd is a cornerstone of Welsh theatre, what are your memories or experiences with the company?

Twm Morys: I have none, I’m afraid! Though I worked for a time years ago next door in the old HTV headquarters, and have taken part in poetry events in the theatre building, I never went to a play there, and I have never worked with the company before!

Garside: Performance has obviously been a big part of your artistic work, from poetry to music. Has theatre been an influence on your work over the years?

Morys: I once auditioned for the part of Glendower in Henry IV, part 1. The applicants had to recite the speech which begins ‘At my nativity the front of heaven was full of fiery shapes…’, while sitting in a big throne-like chair. I didn’t get the part. I was told afterwards that I’d delivered the speech excellently, but that I’d totally ignored the acting. That is, I’d thought only of Glendower’s words, and not of how Glendower would sit in a throne-like chair. Another time, I was waiting in the doorway of a theatre in Rennes. Waiting there as well was an important-looking gent who asked me whether I was in the Theatre? I was waiting for my actress girlfriend, but the man was not Breton and my French wasn’t good enough to explain anything amusingly. So I put one foot through the doorway and said I was half in and half out of the theatre. That is the extent of the influence of the theatre upon me!

But I studied the plays of Brecht a long time ago, and still read them. I have often thought of trying to write a play in that style in Welsh. The type of Welsh popular play called anterliwt, in which Twm o’r Nant excelled, is similar in a way, and I’ve written for, and acted in, performances of this sort, combining poetry and song, with Brecht in mind. Plays all in verse, like Cyrano, fascinate me.

Garside: Do you see similarities between working as a poet, who can be encountered both on the page and in live performance, and the world of playwrights? And the possible challenges of this existing across two forms of an audience engaging

Morys: The kind of poetry I write is meant to be heard, and so should be performed. I think of the publishing of it merely as a way of recording it. I imagine that playwrights feel the same way about their plays. On the other hand, one can of course be moved while reading poetry meant to be heard, or by a play in print. The theatre audience have the acting and the set and the props to give life to the words. The performing poet’s audience have the poet’s own dramatic presence, I suppose, but they must conjure up their own set and props, as it were, from the images and sounds.

Garside: What drew you to want to work with Clwyd as a collaborator?

Morys: I was invited to do the work by the director Mr Breen. The associate director Wil James recommended me, it seems, because of a conversation we had in the Eisteddfod in which I talked excitedly about Cyrano.

Garside: What was your knowledge/experience of the Cyrano de Bergerac narrative previously?

Garside: What was your knowledge/experience of the Cyrano de Bergerac narrative previously?

Morys: I lived in Brittany for ten years with a well-known actress and singer, Nolwenn Corbel. She of course knew all about Cyrano. She gave me a copy on the 29 of April 1990 (the date is written in it!) and I was hooked. A play about the power of language and of words, and all in verse at that, appealed to me greatly. And I thought the poetry very beautiful. That same year the Depardieu film of Cyrano came out in France. I was captivated by that too. I’ve more than once watched it with the text in hand and found it to be very faithful to Rostand’s original. The historical Cyrano (died 1657) interests me as well. He wrote, among many other things, a surreal novel called L’Autre monde ou les états et empires de la Lune (The Other World or States and Empires of the Moon), hence all the moon talk and imagery in the play.

Garside: What have you drawn on in creating your poetry for this piece?

Morys: For the Welsh interpolations and additions to the excellent Anthony Burgess text, I’ve drawn mostly on Rostand’s French original, so that there are two translations at work at once! When Roxane and Cyrano speak Welsh I’ve sometimes incorporated lines or bits of lines from Welsh poetry which will be familiar to the Welsh audience. In some of the free-standing pieces, which are to be used as songs, I’ve used traditional Welsh verse forms, pennill telyn and triban.

Garside: This play is a landmark production using both all Welsh actors and incorporating the Welsh language, was that important for you in being involved? How in particular does this story lend itself to that set-up do you think?

Morys: Cyrano and his fellow soldiers, and Roxane too, come from Gascony in the south of France. They are very proud of their dialect and their accent and their independent spirit. What if in the English production, thought the director Mr Breen, they were made to be Welsh and to speak Welsh? He put this idea to me, and I thought it was a winner. The battle scenes in Cyrano call to mind the Great War, and I was encouraged to think of the Gascony cadets as Valley lads in, say, Ypres. How much Welsh would they, and Cyrano and Roxane, speak and when? Mr Breen sent me a list of points in the play when he thought that, lost in their emotions or remembering their childhood or swearing, they would talk Welsh. The list was added to as the play went through rehearsal. I used southern Welsh dialect words and phrases. Christian, whose northern French accent the Gascony cadets make fun of, was made to be a posh Northwalian.

Garside: Are productions like this, which incorporate Welsh language through poetry, drama music etc, the way forward in preserving and developing Welsh language and culture?

Morys: This production, as I’ve explained, has a particular and interesting reason for being bilingual. In general, though, I cannot stand bilingualism in poetry or creative writing. And the idea that the Welsh language and culture should ride on the back of English to survive makes me reach for my gun! But this in this instance, for my part, this has been an extremely rewarding and worthwhile commission.

Cyrano de Bergerac runs at Clwyd Theater Cymru in the Anthony Hopkins Theatre

Thursday 14 April – Saturday 7 May.