Derec Jones – first and foremost – is a writer. However, he’s a writer who seems to be able, interestingly, to put his hand to many forms and projects. With four novels, a poetry collection, a short story collection, and a ‘random collection’ which includes poems, short stories, plays and snippets, Jones definitely doesn’t come across as someone who struggles with ideas and the variegated writing process. With his own publishing company, Opening Chapter, to boot, Jones can boast of a pretty impressive literary CV.

For those of you who haven’t encountered Jones’ work before, he writes in a varied comportment – as is obvious with his numerous publications. However, what is obvious about his work is that it all, in some way or another, reaches back to life in the South Wales valleys. Whether that be through plot, character descriptions, themes or the occasional nod towards heritage and culture, all of Jones’ work harks back – from the root – to the South Wales valleys. Take his novel, Boys from the Backfields, for instance. The protagonist witnesses a murder at 13 years old, which plagues his life, only to return to the South Wales council estate where it happened, half a century later. And then there’s his poetry collection, The Words in Me, which doesn’t necessarily hover over valleys life like his longer works, but includes subtle flashes of the valleys in its descriptions and backdrops in many of the poems.

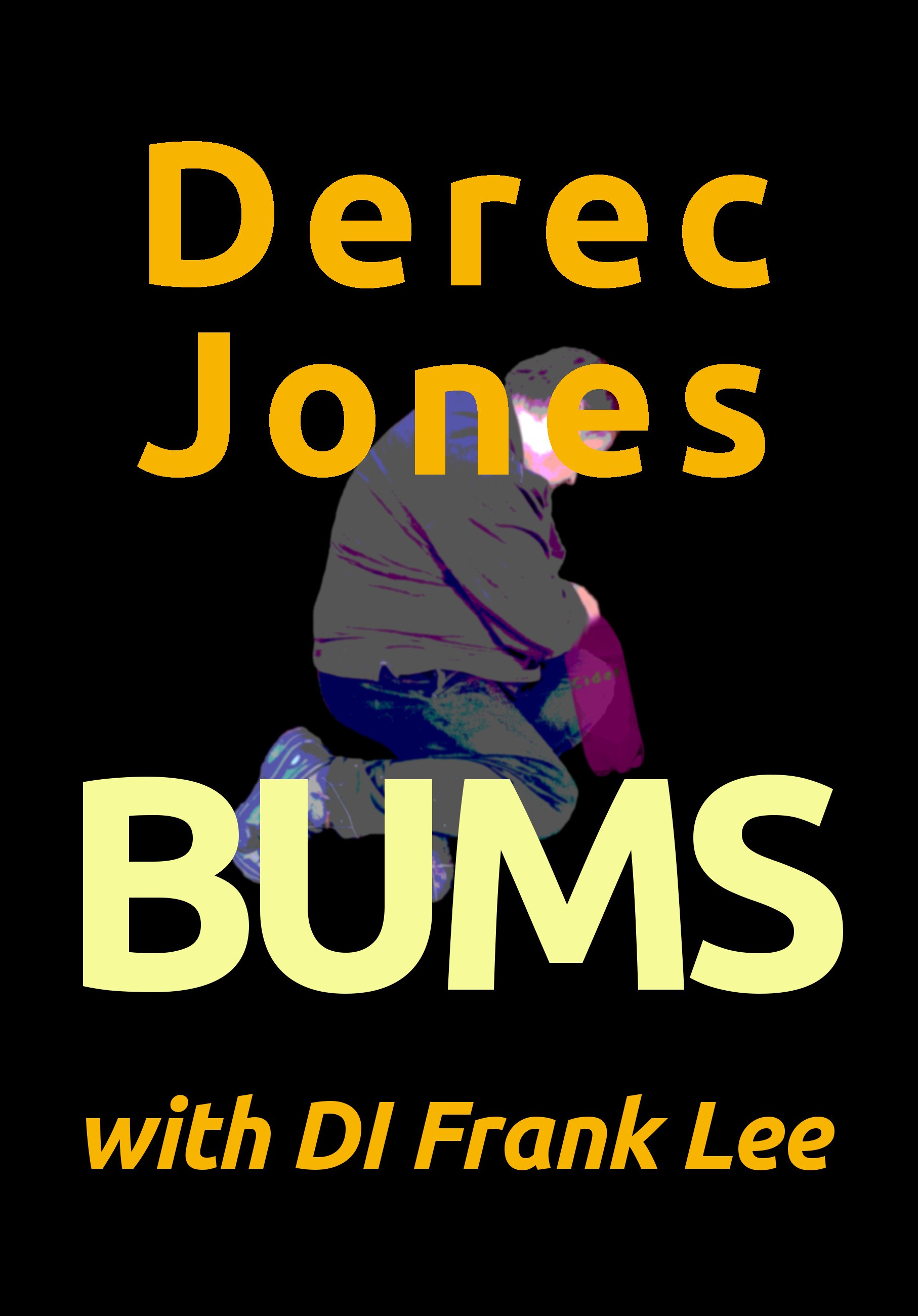

Bums is Jones’ latest novel (his fourth) and it is the first in a trilogy. The others, though details appear a bit sketchy, will be named Beats and Bones. The titles are certainly short and instantaneous, and the cover of Bums does make you want to pick it up. This makes you think – will the novel follow the immediacy we’re pushed into at first glance? And this, I suppose, is a strength.

The novel focuses on a group of very different characters who live in or around the same town and all get embroiled – in one way or more – in the crux of the story. The crux is the death of an apparent pillar of the community: the headmaster of the largest school in the county. The protagonist is DI Frank Lee, a self-proclaimed ex-punk new-age-traveller. The description of Lee is as bizarre as the character’s outlook on life. He seems to breeze through the investigation he’s undertaking without a care in the world – which you’ll find yourself getting very puzzled at – and his dialogue is flat and, at times, forced. Staccato, even. However, other dialogue in the novel saves Jones’ blushes with his protagonist – and you almost nearly forget that Lee is supposed to be taking the leading role. Characters such as Smelly Shelley, Jeff, and Arthur, eclipse DI Frank Lee which makes you wonder whether Jones should have focused more on his protagonist or removed some of the peripheral characters altogether. Lee’s static dialogue, coupled with his outlandish outlook – which is referred to frequently – sometimes makes the novel flow slower than it should:

Frank rolled his eyes, that ‘Sir’ label again and Sam not consulting him – ah well – such were the ways of the world. “Good to have you on board Ianto. Any developments?”

He was glad to be alone – he needed to be alone, to be alone, to empty his mind and reconnect with who he really was, and that wasn’t Detective Inspector Frank Lee.

Bums follows Jones’ knack of placing stories in the South Wales valleys, and this works very well as a setting when you consider a calm ‘sleepy’ town has been curdled by a murder taking place there. However, it does seem to nag at the reader that hardly any use of colloquialism is employed throughout the book. This would have made the dialogue and some of the characters much more believable – and even more relatable. The use of the fictional town of Elchurch is a plus, as Jones has managed to create a town in Wales that could actually exist. Nevertheless, you can’t help but think that Jones shaped a huge task for himself, in placing more than 12 characters in a plot which is already thick with intertwining twists and developments. Some of these characters would have been enough, such as the comedic duo of Jeff and Arthur, the angsty Greg, the ex-partner Flora, the ominous Karl and the very intriguing and likeable police officer, Shaz. With the vast amount of characters, you sometimes find yourself thinking ‘who is this character, again?’, ‘have I encountered these yet?’

Jones does have a knack of allowing comical dialogue in, specifically with the homeless duo of Jeff and Arthur. This dialogue acts as a saving grace and without it, the novel wouldn’t remain as concomitant as it can be:

“Your dick has shrunk so much, it’s almost non-existent,” Arthur said.

“Your brain is shrinking, as well as your knob, you’ve gone senile already.”

“I could do with a piss. What do you reckon Jeff, got any room in those deep pockets of yours?”

“I was having a good fucking dream an’ all. Dusky beauty she was too – all teeth and tits,” he laughed.

Regardless of the sometimes stationary and unnecessary dialogue, the novel is an intriguing read with several linear plots running parallel. This means that you have got to remain alert, or you might miss an important action or development. Jones has done well to conjure up a believable location and even though Frank Lee is, from time to time, an unbelievable protagonist, you still find yourself rooting for him. A tad disappointing aspect of the novel – which felt rushed and tied together a little too easily – was the ending, but it’s still an ending which is satisfying and doesn’t leave you feeling cheated. But, it would have been much more gratifying for an ending which had been built up more and followed a less linear route.

It will be very interesting to see what Jones does with the following sequels, and whether or not DI Frank Lee will remain as peculiar and remote as he comes across in Bums. This is a novel which is contemporary and entertaining but it’s difficult to look back and remember all the characters, which can deem it as unnecessary over-writing. Let’s hope Jones can fix this with the sequels.