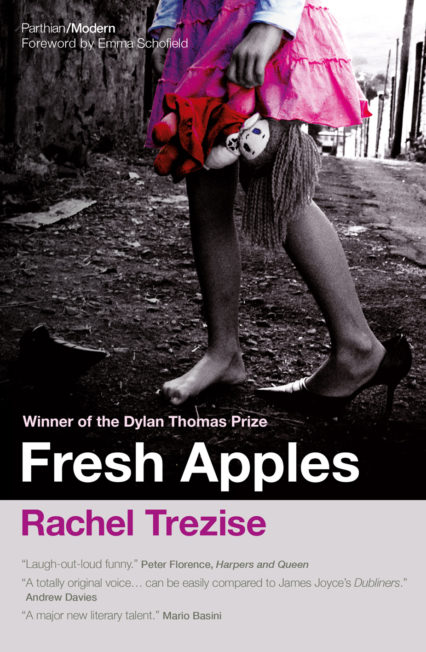

Wales Arts Review is excited to bring you ‘For Their Own Good’, Emma Schofield‘s foreword to the new Parthian/Modern reissue of Rachel Trezise‘s Fresh Apples, a collection of eleven short stories with which Trezise won the Dylan Thomas Prize in 2006.

I first read Fresh Apples by Rachel Trezise on a crowded train, reading the opening pages as the carriage pulled out of Cardiff and wound its way on towards Newport. I remember it clearly, not only because it was evening rush-hour and the train was so packed that I’d found myself perched on a rail in the luggage rack, but because of the distinctive voices which rose effortlessly off the page and drew me immediately into their world. It wouldn’t have mattered where I was, the opening lines of the title story, ‘Fresh Apples’, landed me firmly in the Rhondda.

Rachel Trezise’s decision to locate her first collection of short stories in South Wales was hardly surprising; only four years earlier Trezise had secured the Orange Futures Award with her semi-autobiographical debut novel, set in the area, In and Out of the Goldfish Bowl. The novel catapulted Trezise to the fore of contemporary fiction, leading Harper and Queen magazine to describe her as ‘the new face of (British) literature’. Naturally, such accolades didn’t stop the novel from raising some eyebrows with its brutal portrayal of a young girl growing up around drunkenness, drug-taking, sex and the painful economic effects of industrial decline. None of this deterred Trezise from continuing to draw on the Rhondda, along with nearby Cardiff and Pontypridd as the main backdrop for her stories in Fresh Apples. Trezise’s ability to depict, with effortless brushstrokes, scenes of close-knit communities and tangled families struggling daily for survival is a testament to how well she knows this landscape. Speaking to Trezise in an interview in 2015 I asked her about the importance of place in her writing, to which she responded with the belief that ‘you have to have some knowledge or a feeling of knowing [a place] well’ in order to get the best out of it as a writer. The strength of her personal connection to the area has no doubt informed the depiction of an area so significantly affected by industrial decline and has undoubtedly remained part of the collection’s broader success. Nonetheless, many of the scenes in Fresh Apples, especially those which depict the shadows of industrial decline, job losses and a sense of having been abandoned by wider society will likely resonate with anyone who has spent time living in an area affected by industrial decline.

It is this depiction of social, economic and personal struggles which makes the re-publication of Fresh Apples so timely. Over a decade after the collection was first published, vast swathes of Wales, and indeed the United Kingdom, find themselves continuing to face similar difficulties. Economic challenges compounded by a sharp recession, years of austerity and the continuation of industrial and manufacturing decline have, more recently, been joined by the spectres of new challenges in the form of Brexit and the effects of a global pandemic. Now, more than ever, it is vital that voices from areas where these challenges are frequently at their most acute are heard. In Fresh Apples Trezise offers up personal stories which are often as humorous as they are sad. Like chapters in life, some stories make for entertaining episodes, others make for more challenging reading. Trezise does not shy away from the uncomfortable details in life, instead of embracing them to create characters who struggle with human flaws we can all recognise to some extent.

While the Rhondda remains at the heart of the collection, a number of the stories take us on a whistle-stop tour of other places around the UK. ‘The Magician’ follows a small group of friends as they gather in Cornwall for an ill-fated camping holiday, while ‘Merry Go-Rounds’ charts a visit to London. What stands out about the depiction of these other places is the way in which we are shown them through the eyes of Trezise’s characters; places and identities are constantly referred back to the life they know in their hometown. Even when the characters venture further afield, such as on a trip from Porth to America in the story ‘Coney Island’, the experiences of growing up in the Rhondda and the stark difference between the lives of those at home and those in New York are constant themes. Recalling time spent watching New Year celebrations in Times Square on TV with a friend while still at home, protagonist Meaghan remembers feeling that the people celebrating there, and the city itself, ‘had zilch to do with their own lives’ in Porth. Yet for all that Trezise uses Fresh Apples to celebrate, acknowledge and, at times, lament the struggles of daily life in the Rhondda, the collection carefully unpicks a number of universal themes which transcend the very specific location of the stories. The eleven stories here manage to uniquely capture those complex opposites which adolescence so often brings: boredom and euphoria; resentment and awe; power and vulnerability. Trezise captures the volatility of youth, as well as the excitement and sense of independence it so often yields. These opposites are at play throughout the collection, such as in ‘The Joneses’ in which a teenage boy becomes infatuated with his older next-door neighbour, attracted in part to how different she is from every other woman who lives on his street. Having harnessed all his confidence in a bid to seduce her, he finds himself easily dismissed by his crush but remains undeterred, even when advised to keep his feelings concealed from her potentially violent partner. There is a matter of facts in the way Trezise recounts such stories, emphasising not only how organically they have originated for her, but also the complexity of the lives they centre on. Human life, and the vulnerability of the connections we form, is positioned directly at the centre of this collection.

Given this theme of vulnerability, it is hardly surprising that there is a tone of sadness that runs throughout many of the stories in Fresh Apples. The loss of innocence is everywhere within the collection, from the transition from sexual awakening to assault which occurs in the title story, to the tale of young Michelle in ‘Chickens’, whose grandfather tells her how to kill a chicken only for her to apply this knowledge to the car full of chickens he has just purchased, wringing each one’s neck when they start to make a clucking noise. In the latter part of the story, Michelle’s argument that her decision to kill the chickens ‘was for their own good’ fails to carry weight with her distressed grandfather, who goes on to reinforce the error of Michelle’s actions by calmly denying her any food made with eggs for the coming months. His careful punishment draws only admiration from the young girl, who recalls a realisation that ‘we needed to appreciate the things that provided for us, even down to the lowly battery hen’. The juxtaposition between the cruelty of Michelle’s actions in killing the chickens and the quiet patience of the sanction her grandparents impose on her makes for bittersweet reading.

As is so often the case in life, in Fresh Apples, the loss of innocence is frequently followed by a desire to make peace with the past and to move beyond the difficulties experienced. In ‘A Little Boy’, a pregnant woman, unsure about her future, eventually realises that she has continued with her pregnancy in part because she harbours a desire to regain something of the innocence which was lost from her own childhood. Reflecting on her life so far, the woman’s confession is as touching as it is sad:

‘She knew now why she’d carried the baby to full term. It was because she wanted to give it a childhood of innocence, of games and happiness and protection. It was because she wanted it.’

Her desire to raise her baby in a loving, protected environment reveals her sense of desperation to repair the physical and psychological harm inflicted on her through the sexual abuse she herself suffered as a child. Yet, ultimately, Fresh Apples leaves us with the sense that while the characters in the collection frequently find ways to move forward from the difficulties they face, the past can never be erased. This brings us back to the Rhondda and, more broadly, to contemporary Wales and our own lives. Much may have changed in the intervening years, but the stories are still just as poignant as they were when they were first published. Now, perhaps more than ever, that same sense of frustration and the desire to move forward can be felt most acutely, not only in South Wales but across the UK. Trezise does not offer us answers to that frustration, but in Fresh Apples she observes it, in her own unique style, reminding us of the need to laugh as much as we cry and of the resilience of human nature.

Fresh Apples by Rachel Trezise is available to pre-order from Parthian now.

Emma Schofield is a regular contributor at Wales Arts Review.