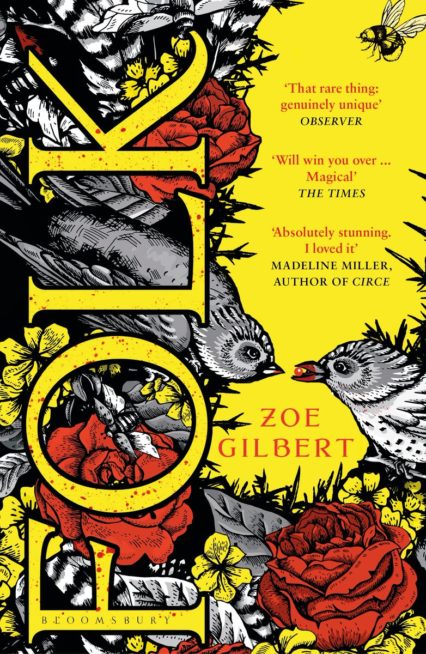

In the run up to the announcement of the winner of this year’s International Dylan Thomas Prize, Wales Arts Review will be publishing reviews of the six shortlisted titles, written by the students of the IDTPrize module at Swansea University. Next up is a double-header, as we publish two reviews of Zoe Gilbert’s Folk (Bloomsbury).

The module is the first English academic study in the world dedicated to a major literally prize and includes access for the students to authors and members of the publishing industry who run tutorials on subjects ranging from book marketing and publicity, to book prize logistics and sales in publishing to help students to explore how literary prizes help to produce, promote and celebrate contemporary writing.

The first review is by Molly Holborn.

Zoe Gilbert’s Folk is a collection of beautifully composed stories that is reminiscent of an older tradition of storytelling, they are tales that should be read aloud around a fireplace on a dark night.

Zoe Gilbert’s Folk is a collection of beautifully composed stories that is reminiscent of an older tradition of storytelling, they are tales that should be read aloud around a fireplace on a dark night.

Gilbert’s style of writing is enchanting, the poetic prose flows easily from beginning to end. It is a book that stays with you long after you’ve finished it. The language forms crystal clear imagery bringing to life the fantastical and the haunting; from a boy with a wing for an arm to a fortune-telling Ox. Gilbert’s writing is confident and potent allowing the reader to trust her story-telling.

The world in which Folk is formed is ‘Neverness’ and it is filled with delight and darkness. The book is fairly short for a fantasy novel and Gilbert’s world-building skills are subtle yet extremely effective in helping the reader to visualise this imaginative world. This is done by forming connections within the stories to form a well drawn vision of a place, adding layer upon layer to ‘Neverness’ leaving the reader at home on this isolated island.

When reading Folk, there are many themes and topics that Gilbert illustrates, much like Aesop’s fables, where there’s always a lesson to be learned. Themes such as grief and loss are formed in the stories ‘Thunder Cracks’ and ‘Earth is Not for Eating’. Desire and lust is brought to the forefront in ‘Prick Song’ and ‘Water Bull Bride’. Gilbert weaves these themes into beautiful fables with the intention of teaching the reader the morals and values that are taught to the children who fall victim to these particular themes. Gilbert reaches back and pulls us from our childhood memories into a very new but familiar world.

Gilbert’s preoccupation with the sea is not only a common motif but a constant reminder of the isolation that surrounds the characters. The isolated island in Folkacts as a mirror reflecting the face of a modern Britain, something that will not get lost on the reader. This novel is unique in its tone and place but underneath the layers of fantasy the reader recognises a comparative reality.

Gilbert’s stories echo a style similar to Arthur Machen; Wales has a lot of forgotten myths and legends, one of them being faeries. In ‘Earth is Not for Eating’ Gilbert tells the story of a changeling, half human and half faerie, she plays on the ambiguity that is the baby’s identity but through haunting descriptions of the pregnant mother Gilbert makes the tale all the more poignant. Machen’s ‘The Novel of the Black Seal’ published in 1895 echoes within this story, as in the tale there is a young boy who is from another world entirely. Unlike Machen, Gilbert is heavily poetic in her writing which makes these short stories vibrant.

Folk is a mesmerising read it incorporates myth and history in a beautifully haunting way. To find a novel that brings back the nostalgia of old-fashioned story-telling is rare within contemporary literature. Folk is a book to be treasured.

The second review is by John Baddeley.

Zoe Gilbert’s novel Folk is poetic and unsettling from its first page to the very last, with heady lines such as, “Gorse Mother. Prick Mother. Drink me deep. Drink me up.” In between the dark folklore Gilbert creates a tapestry of characters whose lives overlap and unfold around each other in stories of love and loss.

Set on the fictional island of Neverness, which Gilbert herself states was inspired by the landscape and life of the Isle of Man, Folkis as much a collection of short stories as it is a novel. Each chapter stands proudly on its own, while simultaneously all are connected by the intense solitude of island life. Characters begin to seep into different stories; a main character in one becomes a subsidiary in another, while a child in the infancy of the text has grown into their own tale by the novel’s end. It is a testament to Gilbert’s ability that each individual thread of a story has been woven so deftly into one novel.

Folklore is the foundation upon which life on Neverness is built around. Gilbert’s stunning vocabulary brings a world of magic and myth to a visceral reality. The boundary between nature and the island’s inhabitants remains blurred and shifting. Those who live there are forced to beat out a living from selling fish scales, ox-hide and damp wood. Life is harsh and unforgiving and is bound in magic and prophecy, superstitions and pagan-esque traditions. In a world where Water-bulls carry brides to their deaths in rushing waters, and a child is born with a wing in place of an arm, the inhabitant’s superstitions feel less like fables and more like couched and clever wisdom. This world is one built on superstition, and it is wholly believable.

Children are central for much of the novel. Gilbert explores the effects of growing up in an inward facing community. The pervasiveness of myth and nature that surrounds them, and its effect on the children’s lives is never far from the author’s consideration. In ‘Prick Song’ boys run through a maze of gorse bushes to try and retrieve arrows that have been fired deep into the tangled branches. Tied to these arrows are ribbons and stitching, signs and favours from the girls of the island. An arrow retrieved promises a kiss as reward on the boy’s pricked lips. This island tradition does not feel like an innocent game and holds a darker resonance with the reader.

‘Long Have I Lain Beside the Water’ tells a haunting tale of tragedy as May’s search for her musical spirit unearths her father’s deep and secret pain at the loss of his first love. Whilst ‘Water Bull Bride’ details how a young woman is taken, in all senses of the word, by the Water-bull in disguise as a soft, lean, longhaired man. Granny Winfred warns of the terrible fate that awaits the young woman but in the end, all that can be saved is a wedding dress made of reeds.

Gilbert’s stories are complex, visual and polyphonic. They run independent of one another, yet a close eye rewards the reader with subtle intertext and hints at an overarching world of Neverness. The beautiful cover, designed by David Mann at Bloomsbury, and the world-map and illustrations that accompany each chapter, designed by lz Simonds (Gilbert’s aunt), lend a sense of reality, permanence and concreteness to the book. They pick up where the beautiful and twisting prose leaves off, establishing Neverness as more than just a space created from our ancient and mythic past landscapes. Prose and illustration combine into something more contemporary than just a collection of fairy tales. Folk is an allegorical vessel that takes the truth of what has come before us, repackages and revises it, and shows how it is just as applicable in our present as it ever was in our past.