Jo Mazelis speaks to Raine Geoghegan – a multidisciplinary artist of English-Romany, Welsh and Irish heritage – about the themes and inspirations behind her latest poetry collection, The Talking Stick: O Pookering Kosh.

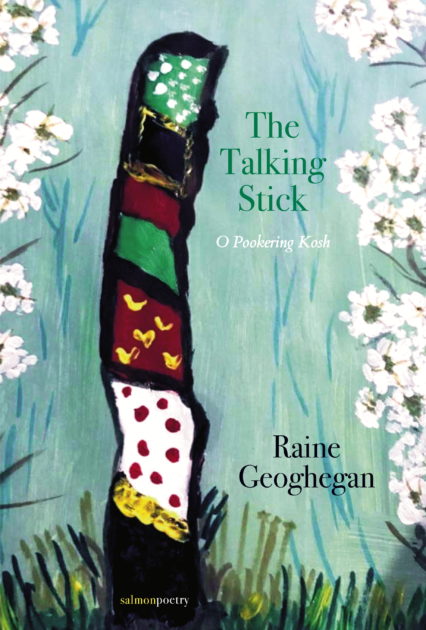

Jo Mazelis: Raine, your painting on the cover of your new book is beautiful and joyful, but also mysterious. The large object that dominates the scene is ‘The Talking Stick’ or ‘Pookering Kosh is so animated that it almost looks as if the stick has a face in profile and a long colourful dress’ – is this purely your interpretation or a traditional representation?

Raine Geoghegan: Although it’s not practised any more, it was once a custom in some Romanichal families that when an elder died, a ritual was performed using the blackthorn stick as a way to pass on wisdom and knowledge from that elder to a small child. I have a talking stick which was carved especially for me by a friend. My publisher Jessie Lendennie suggested that I paint a picture of the stick so I set to work. I couldn’t find any visual references for Romany talking sticks, but I was familiar with the First Nations, Talking Stick. Many years ago I did some training with Oh Shinah, a wise elder from the Cherokee Tribe and I remember her using a Talking Stick in a different kind of ritual. It had bright colours and feathers on it and so I experimented and decided to paint sticks with certain features, patterns and bright colours. I improvised and painted four versions, all seemed to be alive and still growing from the earth. Siobhan Hutson, the designer at Salmon chose the one which is on the front cover and I am very happy with it.

Jo Mazelis: You preface your poetry collection with a quotation from the Romani poet, Bronislawa Wajs, ‘The time of the wandering Gypsies has passed’ if true then it seems a sorrowful thing; the bulldozing of unique peoples and cultures as troubling as that of plant and animal extinction. Do you feel hopeful about the future?

Raine Geoghegan: I feel very sad that even with the passing of time, Gypsies are being treated with contempt and are still a marginalised ethnicity. However, if we look at the world we live in then most of us feel a certain sorrow about the way the world has changed. I feel hopeful that many Romani folk like myself, are sharing stories, art and all sorts of wonderful creative acts. I have seen a burgeoning of Romani creativity since I had my first pamphlet, ‘Apple Water: Povel Panni’ published with Hedgehog Press. We’re on fire, we’re trailblazing a new path for all Gypsies.

Jo Mazelis: I understand you spent some of your childhood in Aberbargoed under the shadow of Europe’s largest colliery waste tip. My family came from Bargoed so it felt like home to me, then Aberfan happened. What do you remember of that?

Raine Geoghegan: I was born in Tredegar, christened in Bedwelty and yes, I lived in Aberbargoed but in September 1957, my father died of kidney disease. He was twenty seven and the youngest of his family. My Romanichal grandfather drove his red lorry to the valleys and took us to live in Middlesex, a place as far removed from the valleys as was possible. My mother was pregnant at the time but didn’t know until two months later. It was tough time for her and she would often retreat into her bedroom, leaving our grandparents to keep us occupied. We used to go back to Wales to visit my Nanna and family but it was always a sad time. I felt my dad’s spirit was still in the house. I have written some poems about him and am hoping to spend some time next year in my birth place in order for me to research the Welsh culture.

I remember listening to the news of Aberfan on the radio and then seeing images of the bodies on the television. It intensified the sadness that I felt about the valleys, a place of death but also of deep beauty and love. Whenever I return to the valleys I get choked up with emotion. Recently I travelled to Porth to read at a Romani Art Exhibition and found myself in tears as I drove past the sign for Tredegar. My heart is in that place and I feel deeply for my ancestors – many were coalminers. They had such a hard life but were incredibly strong. Two of my uncles were in the Bargoed Male Voice Choir and I love the fact that singing has always been a powerful tool for grief and depression, as well as being something that is immensely enjoyable for the singers and the audience.

Jo Mazelis: In the 1980s the Conservative Secretary of State for Employment, Norman Tebbit, suggested the unemployed should ‘get on their bikes’ to find work, yet the Public Order Act of 1986 clamped down on personal freedom and assembly. Nomadic peoples whether Romani or New Age Travellers seem to fall between these two rulings making survival close to impossible. How has any of this affected your life?

Raine Geoghegan: I really feel for those Travelling people who are now faced with imprisonment if they pull their vardos or caravans up on the grass verge or a field. I have written about this and it makes me so angry. I have to say that it doesn’t affect me directly but it does sit uncomfortably within me. It’s always been hard for Travellers to live their lives. The poem, Keep Movin’ from ‘The Talking Stick: O Pookering Kosh’ depicts a scene where the police, (the gavvers) move on my grandparents and their family from the field where they had stopped. It was particularly bad in the ’50s and ’60s but many Travellers grew accustomed to it. It’s never been a fair society. Gypsies have always been treated with contempt. I see my work as a way to challenge this.

Jo Mazelis: Your book uses annotations for Romani words on each page which makes understanding the poems very straightforward. How important is communicating memory and shared experience to you?

Raine Geoghegan: I felt it was important to include the glossary of the Romani words on the page. I wanted the reader to understand the true meanings of the words so that they could be transported back to a way of life that they couldn’t easily imagine. When I read my work aloud I may mention the meaning of certain words but find that the audience understands a lot more from listening to my voice, also from the way I perform the monologues, the stresses I place on certain words, my body language. It’s very different to reading it on the page. I like to think that I bring the characters of my family to life. Much of my initial research and early work has been about finding the voices of each and every one of the people that I write about. I sit in the quiet, listening to their voices, imagining them with me, studying their faces, their body language and then putting it all together to form the poems.

Jo Mazelis: I understand that ill health has led you away from your previous work in dance and theatre, do you find writing as fulfilling? How is your health now?

Raine Geoghegan: Disability and chronic ill health took me away from my work as a professional actor/ dancer/ teacher/ theatre director and founder of a women’s theatre collective. I was forty at the time and had to spend long periods of time in bed, with the curtains closed. It was a challenging time. I had also fallen down the stairs which caused long term damage to my sacrum and coccyx. I’m now registered disabled and have a car through the Motability scheme, which means I am able to travel and be independent. I turned to writing when I was confined to bed because my creative spirit needed to find a way to express itself. Writing and performing my work has helped me to have a life outside of my illness. I still need to rest a lot and take things easy. Many of my health problems are not obvious: I have fibromyalgia; osteo-arthritis and have recently come through Stage 2 breast cancer. I often wonder why I have these multiple health challenges and the one positive thing that has come about has been my relationship to spirit. I have learned to sit in the darkness, to be quiet and to experience closeness to the Divine. Nature too has helped me so much. Nature is a powerful healing presence.

Jo Mazelis: I found the last two poems in your book The Boshamengro – The Gypsy Fiddle Player and The Gypsy Camp at Auschwitz to be particularly affecting – were you always aware of the extermination of the Roma? How did you make the imaginative leap into the mind of the fiddle player?

Raine Geoghegan: Many years ago I started to think about the persecution of the Roma, Sinti, disabled and Polish people in Germany and other parts of Europe. The same day The Gypsy Camp at Auschwitz was published on the Travellers Times website the editor messaged me to say that it had gone viral. There was an outpouring of sentiment on both Twitter and Facebook. As I read the comments, I sensed the deep rage and sadness that many people feel. I was completely overwhelmed by the response.

The Boshamengro was written to honour my great uncle Bill who died after being a POW in WW2. After he was released he went into hospital and died of a stomach complaint, due to having eaten pig swill. He loved the fiddle, his father and brother used to play it so I decided to write about a Gypsy fiddle player. I think I made the imaginative leap into the mind of the fiddle player by homing in on him and his father, making it as close as I could to the real story of Bill Lane while also making it about one among the many who died at Birkenau.

Jo Mazelis: There is a variety of styles in your latest book; poetry and prose, as well as different voices – creating a sense of many people talking and telling their stories. You mix watching Coronation Street on the dikkamengro (TV) with tales of hop picking and life on the road. Did your book emerge organically?

Raine Geoghegan: I feel that my book did emerge organically as each individual poem or vignette came to me lightly. I didn’t have to probe too much, the right words came easily. I have many memories of my childhood and these together with other family member’s stories began to flow. There is still much to write about, things like my dance classes, the shows and winning competitions and also my relationships with each family member. The key for me was to listen, to observe and to focus on the images of childhood which had never left me.

Hop picking was a favourable but tough job to do and yet whenever I listened to my granny and mother telling me about hopping, what was apparent was their sense of joy and delight. They did other things, like pea picking, potato picking, apple picking but hopping was the mainstay. It paid well. It gave them the opportunity to get together with other family members and friends from the road. They would sing and dance. My mother would climb onto a table and sing for all her family while my granny would step-dance. My grandfather used to play a harmonica and the spoons. I would have loved to have witnessed that. My poem ‘Kamavtu’ which was written for my mother and father tells of the time they were in Bishop’s Frome. There was a pub called The Green Dragon and the landlords used to fill up the bath with beer so that the hoppers could put their tankards in and drink their fill. I wrote an essay entitled, ‘It’s Hopping Time’ for the anthology, ‘Gifts of Gravity and Light’ published by Hodder & Stoughton in 2021. Some of the poems from ‘the Talking Stick’ were also published there. I’ll leave you with the last few lines from a haibun entitled, ‘A Table in the Hop Fields’ on page 71.

‘hungry finches/ waiting for crumbs/ as we ate our grub/ a bell rings/ it’s hopping time’.

Thank you, Raine. I really appreciate your taking the time to talk to me and look forward to reading more of your work.

The Talking Stick: O Pookering Kosh by Raine Geoghegan is available via Salmon Poetry.