In a major celebration of the life and works of one of Britain’s great literary figures, Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw hosted a collection of tributes to Jan Morris in her 90th year. Here Wales Arts Review is proud to present a panoply of the work that was created for the exhibition, including essays by the artists and an exclusive introduction by the exhibition’s curator, Iwan Bala.

[This article was originally published in Wales Arts Review on December 11th, 2016]

‘An Introduction’

by Iwan Bala

Kindness, according to Jan Morris, is the philosophy she would most espouse for the better world, and on her ninetieth birthday in October, it seems such a concept is still a long way from informing the world’s politics. But at Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw in Llanbedrog on the Lleyn peninsula on the week-end of October 14th and 15th, kindness was much in display. I had been fortunate to be invited to curate an exhibition and event to celebrate her life and work. An extraordinary and humane life, a life of writing about places (not ‘travel writing’ I hasten to add) of informed and entertaining chronicles of Empire, of imaginative evocations, of journalism (famously from the conquest of Everest and the Suez debacle that signaled the end of Britain as an Empire) and of a life of duality, Military/Civilian, English/Welsh and Male/Female. But it is as a Welshwoman, living locally that she was celebrated, in a warm companionable meal at the Plas on Friday night, and a morning of erudite talks by Angharad Price, Paul Clements, Derek Johns, and David Lloyd, chaired with dexterity by Jon Gower on a Saturday morning. The afternoon saw the opening of the exhibition and a public conversation between Jan and her son Twm Morys with the hall of the Plas overflowing with listeners and viewers. Guto Dafydd and David Lloyd contributed a new poem each for the occasion, the title of the exhibition taken from David’s poem, ‘A Journey, for Jan Morris’. Twm and Gwyneth Glyn also provided musical interludes.

The fourteen artists contributing each exhibited work inspired by one aspect or another of Jan’s life and work. Christine Mills created wool felt book-covers, using wool from sheep around Jan’s home, Trefan Morys, and sea water from nearby Criccieth. Carwyn Evans displayed a photograph of books created from studio debris, MDF and chipboard books to the size of Jan’s published works. Books, and Jan lives in a converted coachouse that is as much library as home, are central to her life. Places too, were explored, Everest by Sara Rhoslyn Moore, juxtaposes a film she made climbing Snowdon and a reference to her father’s occupation, selling Everest double glazing. Everest appeared again through clouds in a painting by Lisa Eurgain Taylor, Manhattan is in the photographs of Aled Jenkins, and shadows of Venice in Rhian Haf’s work. Tim Davies’ film ‘Frari’ done for his Wales at Venice biennale representation, alludes to the ‘sense of place’ of Venice. Kim Waale from NY state contributed dozens of paper boats in the shape of Wales, and of leaving and returning. Iwan Gwyn Parry painted Enlli as a mystical island always beyond reach. Ivor Davies made a wall hung assemblage (a ‘Combine’ as Rauschenberg would have called it) of ‘things’… lead soldiers, maps, newspaper cuttings, army gear and his own childhood drawings of airborne dogfights, to evoke a museum of British wartime memory, of ‘Boy’s Own’ derring deeds and exploration. Peter Finnemore showed a film of clips that pertained to the ‘matter of Wales’ and which induced a similar nostalgic reverie in the viewer. Annie Morgan Suganami came with me to visit Jan, and produced two large portraits. Both Craig Wood and myself exhibited works based on maps, maps that Jan studies, and keeps along with the thousands of books at Trefan Morys. Maps indispensable to the study of the world, both real and imagined.

The fourteen artists contributing each exhibited work inspired by one aspect or another of Jan’s life and work. Christine Mills created wool felt book-covers, using wool from sheep around Jan’s home, Trefan Morys, and sea water from nearby Criccieth. Carwyn Evans displayed a photograph of books created from studio debris, MDF and chipboard books to the size of Jan’s published works. Books, and Jan lives in a converted coachouse that is as much library as home, are central to her life. Places too, were explored, Everest by Sara Rhoslyn Moore, juxtaposes a film she made climbing Snowdon and a reference to her father’s occupation, selling Everest double glazing. Everest appeared again through clouds in a painting by Lisa Eurgain Taylor, Manhattan is in the photographs of Aled Jenkins, and shadows of Venice in Rhian Haf’s work. Tim Davies’ film ‘Frari’ done for his Wales at Venice biennale representation, alludes to the ‘sense of place’ of Venice. Kim Waale from NY state contributed dozens of paper boats in the shape of Wales, and of leaving and returning. Iwan Gwyn Parry painted Enlli as a mystical island always beyond reach. Ivor Davies made a wall hung assemblage (a ‘Combine’ as Rauschenberg would have called it) of ‘things’… lead soldiers, maps, newspaper cuttings, army gear and his own childhood drawings of airborne dogfights, to evoke a museum of British wartime memory, of ‘Boy’s Own’ derring deeds and exploration. Peter Finnemore showed a film of clips that pertained to the ‘matter of Wales’ and which induced a similar nostalgic reverie in the viewer. Annie Morgan Suganami came with me to visit Jan, and produced two large portraits. Both Craig Wood and myself exhibited works based on maps, maps that Jan studies, and keeps along with the thousands of books at Trefan Morys. Maps indispensable to the study of the world, both real and imagined.

My own understanding of Jan’s writing keeps developing, as I read more and more of it, a humane understanding of the world seems to blossom in my head… and it might well be my companion until death. Until I read the ‘Pax Brittanica’ trilogy, I never understood the random, shambolic nature of the British Empire, and therefore, did not understand it’s significance to my own life. No one could be a better guide to an understanding of this, through humane and ‘kind’ reportage, but reportage that is nonetheless, damning.

But, as I said all along, it was meeting Jan, having some relationship with this person, Jan Morris, that is the most direct inspiration. There is no one quite like Jan Morris… there never will be again. And visiting Trefan Morys, to be welcomed, cosseted with tea or a malt whisky, to feel honoured (though undeserving), is to witness Kindness in action.

‘A Continent of Prose’

by David Lloyd

Jan Morris’s books cover an immense range: art, history, diverse cities, the human psyche, literature, geography, architecture – and these are the tip of the thoroughly-researched and personally-experienced Morris iceberg. But “iceberg” doesn’t work: it’s too cold a metaphor. Let’s call it the Morris continent: a densely-populated land mass, inviting a lifetime of exploration.

What strikes me the most while reading Jan’s “continent of prose” is the onrush of language. I love to read about history and culture – the byzantine ways humans organize ourselves, individually and together. And I take “humanity” broadly construed – Jan’s humanity, and the humanity (and inhumanity) of all humans through history in our disparate places – to be this writer’s ultimate subject.

But what has most inspired me are her written words, the letters themselves on the page, accumulating, pausing, stopping, rushing ahead again. Last spring I spent many hours revisiting Jan’s Pax Britannica trilogy on the rise and fall of the British empire, which escorted me through the corridors of power and the alleyways of the dispossessed, an achievement on a grand scale, with the world as the setting. Just prior to that excursion through the Morris continent, I read Contact! A Book of Encounters, a recent collection of vivid, fleeting interactions between Jan and men and women (and children) encountered over a lifetime of travel – an embodiment of how the grand scale of human life is the sum of such moments that arrive and dissolve: “between Here and There, to Him or Her, after Then and before Now,” as Jan phrased it.

Language for the grand scale and the sharp moment – that is Jan Morris’s gift. Humanity may be her massive subject, but words are her medium – and she is a master.

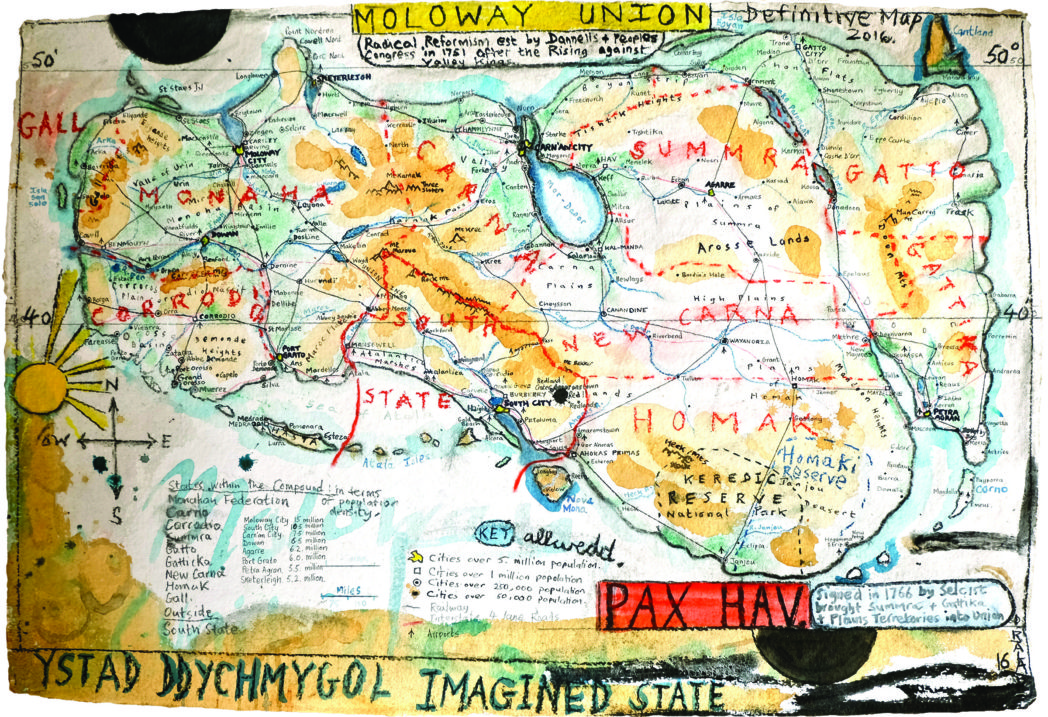

‘Pax Hav’ by Iwan Bala (mixed media on Khadi paper, 2016)

In my visual and intellectual response to Jan Morris, her work and her life, I have attempted as much a multi-faceted approach as possible in a small space. I have attempted to invoke her own wide-reaching creativity, in travel writing, in imaginary writing, in historical and political writing, in her deep interest (obviously for a traveller) in maps. And, of course, in her deep identification with Wales and its struggle for survival. The Eton Mess should therefore strike an amusing note for the author of Pax Britannica.

Thus, I have appropriated the Italian marble classical sculpture in the space, and made of it a talisman. A mother cradling, but also offering her child, the fruit of her creativity. Added are slabs of Kilkenny marble (brought to mind by the knowledge that Jan and Elizabeth’s tombstone already resides with them in their home), on these are the simple words; Geiriau (Words) and Marmor (Marble). This represents the monument of words that exists in Jan’s honour.

I have ‘borrowed’ from the A Writer’s House in Wales, several tokens of interest that are part of the collection, surrounded by books that cover every wall of the house. Amongst them a wonderful depiction of Venice by Jan, made in 1979.

In celebration of Jan’s ‘imagined’ country’, Hav, written about in two volumes, I have created a map of my own ‘imagined’ country, well, the first map to be displayed to any other human being at least. I began to construct this place when I was eleven or twelve, and it remains clearer in my head than most ‘real’ places.

‘The Matter of Wales’ by Ivor Davies (mixed media on canvas, 2016)

While rendering my statement into English I wonder if the reality is different from the original Welsh attempt to reveal the truth about how these pictures were done, the act of thought and materials. Explanations or analyses of pictures are like explications of the world, or of life itself.

In 2009, beginning to design a figure of St David, I stretched thick paper and gum-stripped it on to canvas as taut as a drum. This canvas, with traces of the strips, is the basis of two new works for this exhibition. After experimenting with various pure blue pigments, such as indigo from plants and other azure hues from iron

and copper, I spread the coagulated casein mixture onto worn cotton bedclothes and placed these on that paper and canvas support. The colours penetrated through into the underlying layers.

Thus began The Passionate Sightseer on paper and The Matter of Wales on canvas. Unexpected grainy textures appeared suggesting oceanic stretches with hills and mountains in the distance. Undecided whether to take this propitious result further, it seemed possible to transform some of the small accidental marks into a map of Wales like a dragon; a long strip of train, racing from one side of the picture to another; one or two distant eagles; and an aeroplane, as well as the grainy marbled remains of a column at the right edge surmounted by an ironic Ionic capital. After this it seemed to be the picture which determined the signs: I did not know from where the giraffe had come and is there a bear, or is it is an ant-eater, nearby? From where was the yellow, white and blue banner imported? What is the yellow ink descending from the pen in the sun? And is this Jan Morris’s hand?

Friar by Tim Davies (film still, 2011)

… my eyes strayed upwards, above the tumbled walls of the courtyard, above the gimcrack company of chimneys, above the television aerials and the gobbling pigeons in their crannies, to where the great tower of the Frari, regal and assured, stood like a red-brick admiral against the blue.

In making new site-responsive work to be shown at the 54th International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale of Art, Tim Davies was given access to the usually publicly inaccessible interior of the Campanile of the Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. Located in the heart of the San Polo district, the Frari, as locally known, is one of the greatest churches of Venice with its campanile, the second tallest after that of San Marco, completed in 1396.

Davies records each step of the journey up the inner ramps of the architectural structure, investigating the unique, specific physical qualities of the tower. As the camera moves higher, leaving the chatter below, the sound of the Frari bells build gradually, bells that would have called to prayer, alerted residents in times

of danger and celebrated important dates. The arrival at the belfry itself is deliberately left unresolved and out of location, as Davies said: “It’s not as if I’m looking for the view, which would be a given from such a height as the Frari campanile, but more a sense of finding yourself in a unique, elevated position. When you do emerge into the belfry the first thing that hits you is the intensity of the light.” Silence is momentarily held as the architectural image bleaches before a quick descent making this a work that acts as a meditation on place as well as the passage of time.

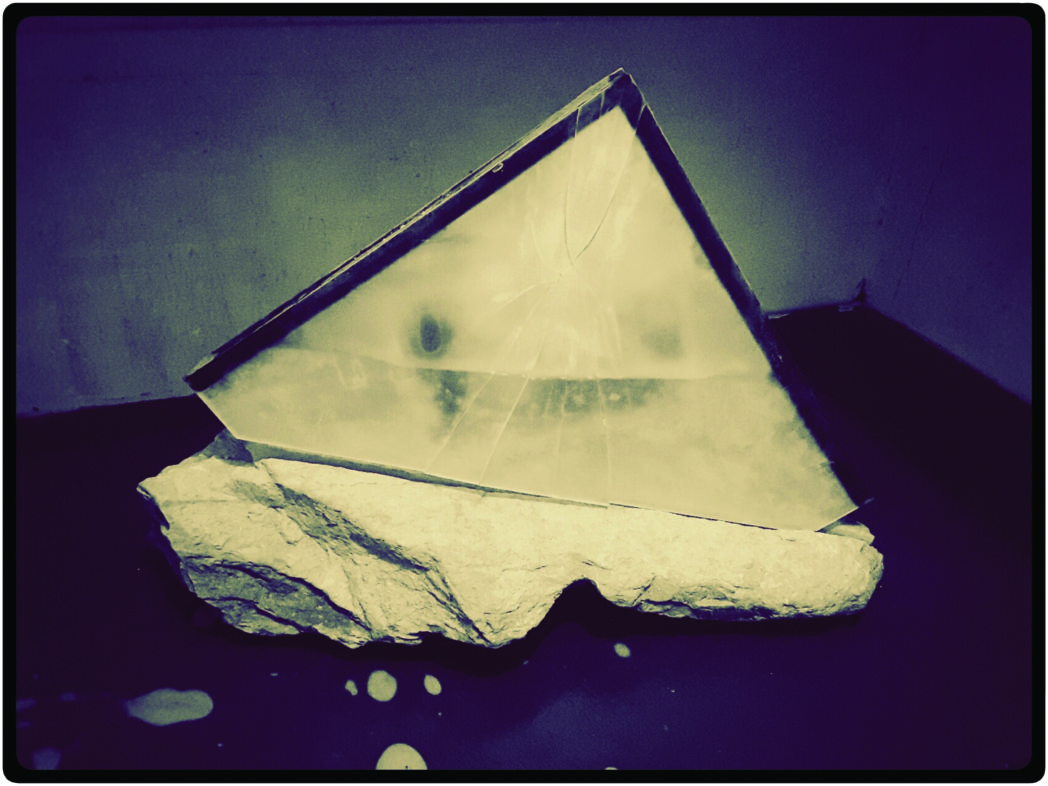

Library (Jan Morris) by Carwyn Evans (Detail; one part of diptych: digital print, 2016)

Book lovers will understand me, and they will know too that part of the pleasure of a library lies in its very existence.

Made from offcuts in the artist’s studio, and fashioned to the dimensions of Jan Morris’ published works, Library is an ode of sorts to a literary oeuvre. Here, presented chronologically and clinically in material form, these books withhold identification and the ability to unpick the subject from the object. This is the ’existence’ it occupies. Library is both made from, and foreign to, its environment.

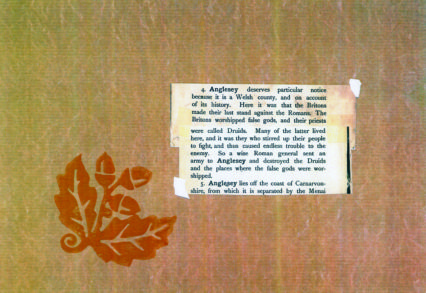

Lesson 56-59 by Peter Finnimore (film still, 2016)

In the 80’s when I was absorbed with ideas of identity and how to visualise identity construction and history, my root question was, what is Cymru? what is Wales? Is it a country, nation, province, a principality, a domain… ? and what the hell was the ‘Marches’? I read copiously, mainly second-hand books which contained narratives of Welsh culture and history. Whilst Jan Morris’s book the Matter of Wales was an important read, it was her lesser known book Wales – Small Oxford Books, 1982, which really inspired and motivated me to visualise Welsh history. It is an “anthology of Cymreictod, Welshness, the consciousness of being Welsh”. Morris charts a literary and historical travelogue, compiled through fragmented and montaged texts from Welsh history. I liked its modest and subversive form, its quiet authority and its non-judgmental scholarship.

In the 80’s when I was absorbed with ideas of identity and how to visualise identity construction and history, my root question was, what is Cymru? what is Wales? Is it a country, nation, province, a principality, a domain… ? and what the hell was the ‘Marches’? I read copiously, mainly second-hand books which contained narratives of Welsh culture and history. Whilst Jan Morris’s book the Matter of Wales was an important read, it was her lesser known book Wales – Small Oxford Books, 1982, which really inspired and motivated me to visualise Welsh history. It is an “anthology of Cymreictod, Welshness, the consciousness of being Welsh”. Morris charts a literary and historical travelogue, compiled through fragmented and montaged texts from Welsh history. I liked its modest and subversive form, its quiet authority and its non-judgmental scholarship.

The most poignant and revelatory text for me was Jan Morris’s inclusion from the Act of Union 1536. I had never seen this before and here I was, presented with the root legislative text that would define Cymru / Wales for the next half millennia. ‘Annexed’, ‘united’, ‘incorporated’, ‘subject to’, ‘under the imperial crown of this realm’, ‘king’s dominions’, ‘ no persons that use the Welsh speech or language shall have or enjoy any manner of office or fees within this realm…’ etc. These phrases are touchstones of power that endure. Marginalisation is both a historical and continual process, through legislation, culture, economy and symbol. Through time, these power relations become normalised and invisible.

In response, my Lesson 56 – 59, seeks to critique and visualise power, identity and narrative and, similarly to Morris’s ambitions in Wales, seeks an unfolding future through cross-generational dialogue.

Campo Pescheria, Venice, 2011 by Rhian Hâf (photograph)

….To me gender is not physical at all,

but is altogether. It is soul, perhaps,

it is talent, it is taste, it is environment,

it is how one feels, it is light and shade….

Silent transient moments, the play of light and

shadow within architectural spaces, subtle and often unseen and unnoticed, are primary elements of my practice. It is a subject of creative imagination where my artistic process involves translating and developing personal observations. Predominantly working with glass, photography plays a key element within my research. During time spent in Venice I was inspired to capture the city through its shadows. Portraying an unfamiliar perspective within a familiar setting by highlighting the city’s formations, character and atmosphere, presenting a glimpse of the surrounding environment. ‘Manhattan’ by Aled Jenkins (photograph, 2010)

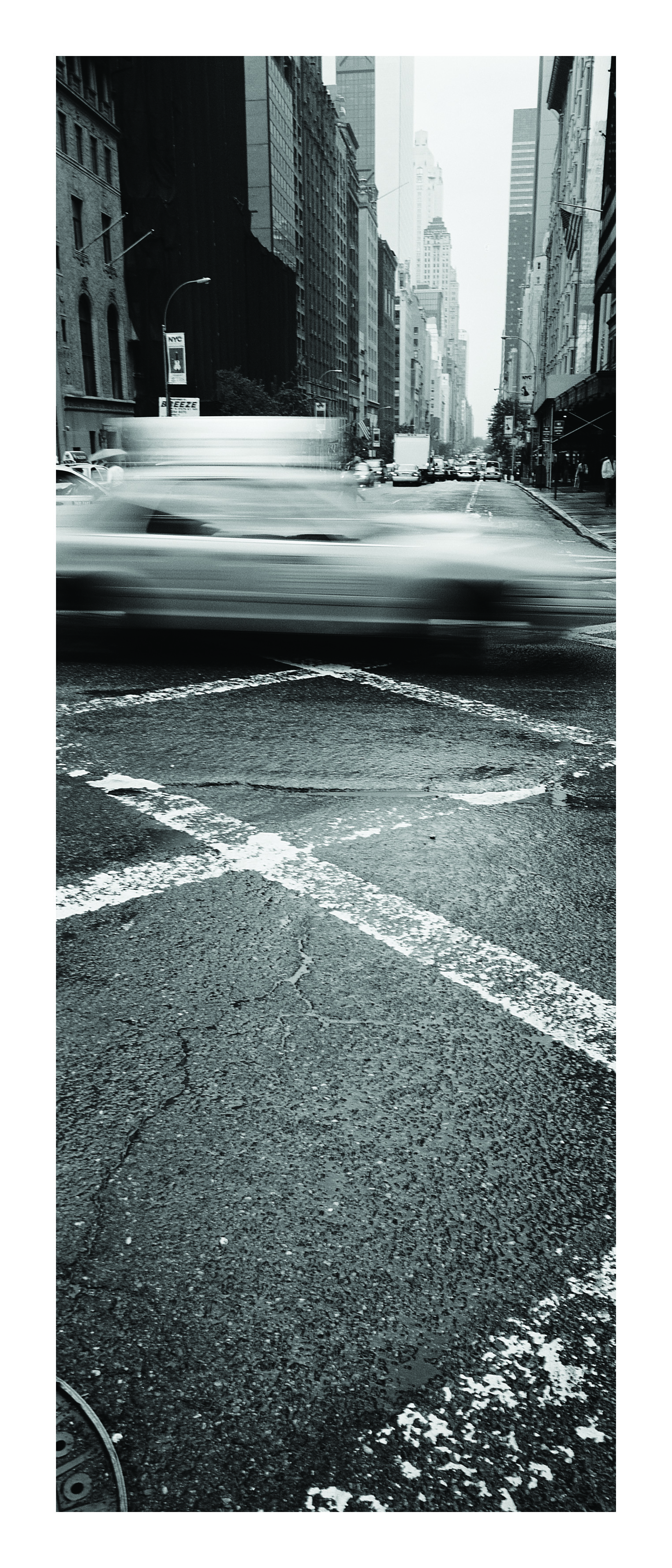

‘Manhattan’ by Aled Jenkins (photograph, 2010)

Jan Morris has been of inspiration throughout my photographic career. The way that she interprets a city gives a visual sense of the place, which stimulates and motivates the creation of my work.

Having read her books on Manhattan and Venice, her enthusiasm and passion for both cities is contagious.

Jan’s book, Venice, has been a companion during my travels to the city, providing an historical context to the creation of my own images. The images were taken early on a winter’s morning in December, capturing a somber air of melancholy that prevails in her book. The Venetian architect and historian, Francesco de Mosto, described Jan as the “only non-Venetian writer to have captured the essence and soul of the city”.

Manhattan provides a stark contrast to Venice, with its fast pace and modernity, where change is to be embraced. The New York taxi is iconic of the city as it speeds along Fourth Avenue.

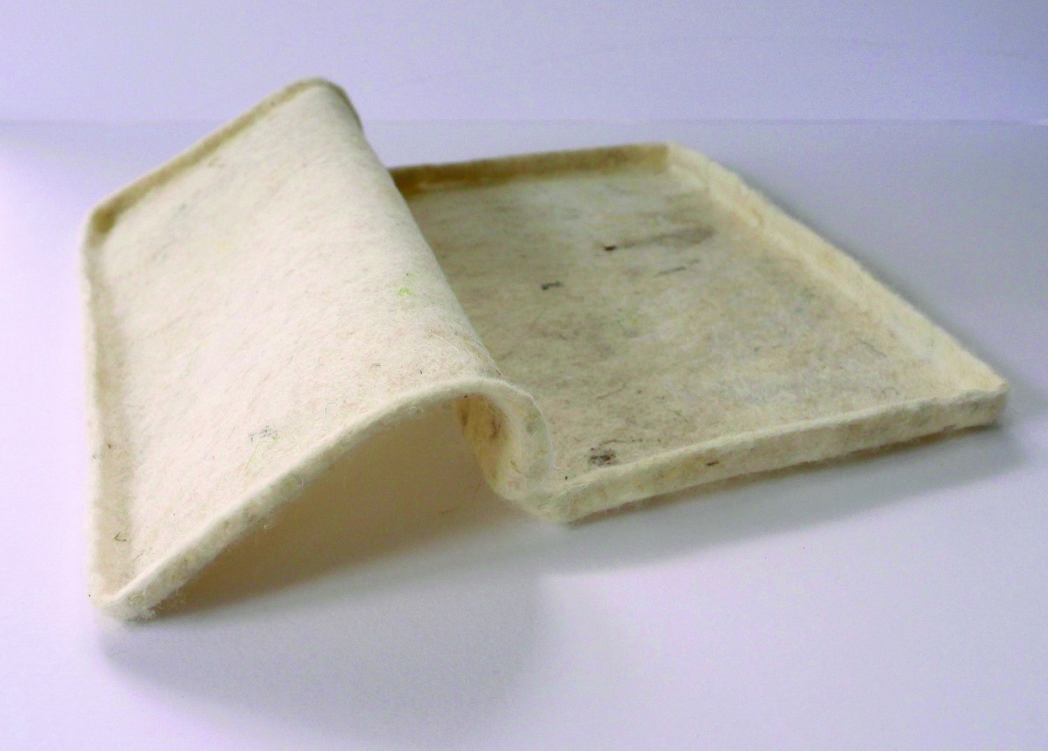

‘Between the mountains and the sea’ (where Jan Morris lives) by Christine Mills

A collection of ‘casts’ or wrappings taken from a collection of Jan Morris’s books. These ‘casts’ or wrappings create jackets that are made from the products of the Welsh mountains (Welsh mountain sheep’s wool) bound together by the use of the sea (Ceredigion Bay sea water)

The oldest publishers’ dust jacket now on record was issued in 1829 on an English annual, Friendship’s Offering for 1830. It was discovered at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

… After publishers’ cloth bindings started coming into common use on all types of books in the 1820s, the first publishers’ dust jackets appeared by the end of that decade … These books often had fancy bindings that needed protection. The jackets that were used at this

time completely enclosed the books like wrapping paper and were sealed shut with wax or glue.

… Most jackets of this type were torn when they were opened and then discarded like gift-wrapping paper

(quote from Oxford English Dictionary)

‘Between the mountains and the Sea’ ……a special place to be, but, the gifts are found inside.

Cast of Jan Morris book from Welsh mountain sheep wool and Cricieth sea water

Annie Morgan Suganami

I often return to using fluorescent yellow, gesso and charcoal for portraits. Jan greeted me at her doorway, as if she knew. She was wearing yellows, creams and whites, topped with that wonderful head of white hair.

Sorted, I thought.

I started with a large sketch as soon as I got home, hoping that fresh memory of our meeting might guide me.

The two portraits are like film stills from our meeting that day.

‘Bardsey, meditations on a land beyond time’ by Iwan Gwyn Parry RCA (oil on linen canvas, 2016)

Enlli, meditations of a land beyond time has been indirectly inspired by Jan Morris’s book , a favourite book of mine. It is a magnificent book celebrating Wales and all things Welsh. It is a deeply felt personal study but yet universally accessible, and I am sure will be relevant for each generation that reads it with care.

If the measure of all great works of art is Time, then Jan Morris’s art transcends Time, and this book, like its spiritual predecessor Wild Wales by George Borrow will leave a mark for years to come.

As an artist I use both figurative and abstract languages to construct my images. An attempt to combine both languages in a single image so that the work conveys the “seen and the unseen”. Ultimately what cannot be seen can be felt.

My paintings are unearthed rather than observed, layer over layer over time. They attempt to convey memories and experiences which have left an indelible mark upon me. Bardsey is a romantic emblem of all that is mystical about Wales; a timeless, symbol of our Celtic past and a place which remains “in the mind” of each who witness it’s enchanting beauty. I have attempted to convey its mystery and romance.

I am very pleased to contribute to this exhibition that honours this remarkable person and I hope that my painted work evokes the same spirit and passion as that of the author we are here to celebrate.

‘Everest’ by Sara Rhoslyn Moore (photograph, 2016)

This piece, made especially for this exhibition, has challenged me to push my boundaries and ideas as my work usually explores my Welsh identity and culture through personal experiences. Researching and creating this piece encouraged me into thinking of a broader sense of self and the experiences of others, and their effects on the whole world.

It was May 29th 1953, Hillary and Tenzing Norgay completed their mission, and stood on the summit of Everest but for Morris, a journalist covering the expedition, only half of the assignment was completed.

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was approaching and getting the news of British mountaineering success to The Times to coincide with the coronation would be a coup, not only for the propaganda value, but for the successful completion of Morris’s assignment. On the 2nd of June 1953, the day of the coronation, the journalist’s career reached its height. You couldn’t get any higher than Mount Everest.

In response I climbed Snowdon, the mountain the Everest expedition would have exercised on, in an attempt to experience being in the shoes of an inexperienced climber with an assignment to complete in time for a special occasion, mine being this exhibition, for Jan Morris’s 90th Birthday. The installation piece itself resembles an award of achievement, a visual journal of one of the most famous stories of exploration. It seeks to capture the two mountains, and both art and man, exploring the world.

From ‘Pen y Gwryd to the Top of the World’ by Eurgain Taylor (detail, acrylic on canvas, 2016)

Snow conditions bad. Advance base abandoned yesterday. Awaiting improvement. All well!

The secret code used by Morris to tell the world that Everest had finally been defeated. Morris had combatted perilous conditions on the mountain and, despite being pushed to the limits by the ascent, described the experience as being a “romantic” one. I convey this alluring mystery, combining the terrain of Nepal with that of Nant Gwynant, used by the ‘Pen y Gwryd’ group for training purposes, returning there frequently on anniversaries. Despite the despair Morris felt on the slopes of Everest, the fears were overcome by the drive to win the race for “the scoop”. Hillary and Tenzing were not the only victorious ones that day – it was Morris who triumphed in breaking the news in the press. The light amidst the darkness in the painting is representative of Morris’s efforts, perseverance and victory.

Following the conquest, people flocked to ascend the mountain – no longer insurmountable; the concept of it being invincible and impossible was gone. Morris despaired, seeing it now as “some magnificent wild beast, dressed up for a circus performance or a TV show”, and controlled by both man and the media.

She sympathised with the mountain but the charm she once felt had now faded.

Following the earthquake in Nepal in 2015, we were all reminded of the perils of Everest and its ominous powers. Despite the tragedy and sadness, Jan Morris’s adoration of the mountain was rekindled; “Goddess Mother of the World” was now free of man’s intervention, and stood in the “mystery of its own.” I convey the importance of ‘Chomolungma’ with its deserving place in the painting – so still and peaceful – “on top of the world.”

‘Hand Made Place’ by Kim Waale (watercolour and ink on paper, 2016)

Ursula K. LeGuin ends her “Introduction” to Jan Morris’s Hav by calling it “a very good guidebook,” albeit to a thoroughly invented place, ”not recognised in the atlas or the histories.” Morris herself wrote in the new “Foreword” to The World of Venice that the book, which defines Venice for so many readers, is “nothing like the objective report [she] had originally conceived.” Instead, “It is Venice seen through a particular pair of eyes at a particular moment.” This is of course not to say that Morris invented Venice; however, she did invent Venice for herself, and she shares it with readers—opening all of their senses to the experience of place, so they can invent the place for themselves.

The installation Fleet/Llynges and related paintings are about the subjective nature of place and how experiencing far flung and nearby places with open senses (in the spirit of Jan Morris) actually recreates/reinvents/re-forms/reshapes the places we think we know.

From The New Map Series by Craig Wood

The New Maps Series is an ongoing body of work created as a response to the major global changes currently unfolding in the early 21st Century. Issues such as the economic and cultural shifts in power between East

and West, migration and globalisation are international dynamics which have a profound impact upon every detail of our lives. Wood tackles these phenomena in a characteristically reductive manner and utilises his experience of ‘mapping’ gained through working as an architectural and archaeological draughtsman.

The work exhibited in this exhibition is a development of the more illustrative ‘painting on maps’ pieces created for solo exhibitions at Oriel Davies, Newtown and The Three Gorges Museum, Chongqing, China in 2015. Here, Wales’ physical scale and geographic position relative to the BRICS nations was brought to the fore by applying sea-blue paint to commercially printed world maps.

Similar techniques are utilised in these current works, but we are introduced to a more abstracted and predictive proposition. These maps are not intended to be accurate political or environmental forecasts, but allude towards a very different future where physical and cultural boundaries have become unrecognisable. The New Maps Series allow these transformations to be considered, but also represent a call to actively create new maps defining our own future.

‘Methods’

by Twm Morys

I have known Jan Morris now for over half a century, and during that time I’ve observed her methods and her habits in some detail.

There’s nothing sullen about her craft or art, and she has never, even in her youth, been one to work at night. She goes to bed around ten, and gets up early. By nine she’s reading the world news on her ipad with her toast and marmalade – a different marmalade, by the way, for every morning of the week. Then she’ll read her emails, which are many and varied. Soon the post will come, and maybe there’ll be a card from an old friend, a soldier or a bishop, in a shaky and absolutely illegible hand. Maybe there’ll be a letter from a historian who would like to draw Jan’s attention to an error on page 538 of Heaven’s Command, or a letter from someone who’s read all her books and feels she must write, though she’s never written to an author before. Maybe there’ll be a letter from a young aspirant, breathlessly thanking her for the inspiration…

She has given up writing books, of course, and now only ever writes reviews, forewords, articles, essays

and thought-pieces, or adds to her posthumous work, Allegorizings, which will run off the press the minute the word is given that she has kicked the bucket. A day’s work conforms to the same strict principles as it always has: that almost nothing gets in the way of the day’s quota of words (around 1,000 at one time); that she writes three drafts of everything (the first sometimes the best); that she goes for a walk, set nowadays at a thousand paces, as far as a certain gate on the Trefan lane where she has twice experienced a vision or epiphany.

When she goes for her walk alone, she whistles some military march to regulate the pace, and then turns over the morning’s work in her mind. But when one walks with her, then she tells stories; maybe the one about the Suez Canal and the French airmen, or the smile of the solitary Tibetan monk gliding down Everest towards her, or – my favourite – the relaying of the news to the sub-editor of The Times that the coelacanth had been found alive and well! ‘Well I never! The… um… coelacanth, you say? Well, well done, Morris, well done. Run along now…’

Jan never really makes herself the hero of these tales, but rather just the necessary observer, and sometimes the story will not concern her at all, but be an episode from history, especially British Imperial history. I remember well to this day the Battle of Isandlwana fought out again high up on the slopes of Pen-y-Fâl in Monmouthshire. And all these stories are full of asides, corresponding exactly to the footnotes Jan is so fond of in her writing: the national anthem of Siam, for instance, sung to the tune of ‘God Save Our Gracious Queen’: ‘O Wotta Na, Siam…’

One of my first clear memories is of lying on top of the garden wall in the summer in Trefan, listening to

the clack-click-clack of the typewriter through the open window of the study. That sound – which we don’t hear anymore in this country, of course – is to me still the sound of the good-humoured but unflinching artistic discipline which foolish people call selfish, and which I wish I had inherited!

You might also like…

Jan Morris bemoans the incursion of modernist materialism that is upsetting her romantic take on Wales.