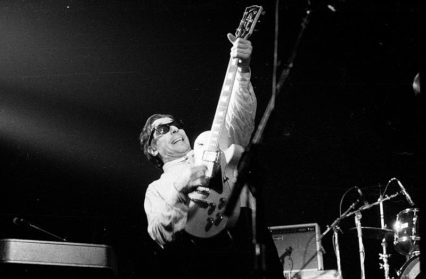

Max Ashworth charts the final flings of Swansea’s greatest son and the band that launched a thousand ships – settle in the for fascinating story of John Cale and the Velvet Underground.

“Hello campers!” hissed John Cale from the Park stage at Glastonbury 2008. “We’ve come to break your hearts!” And break our hearts he did. The set comprised of nothing from Vintage Violence, Paris 1919, Fear, Slow Dazzle, and nothing remotely Velvety. The band even ended the set with a ten-minute jam, FFS!

It is maybe an unremarkable feat, but by playing a kinda un-gig, a letdown set utterly bereft of any hits, an album track jukebox without choice, really turned me onto his back catalogue. There’s certainly a ‘why-should-he-just-reel-out-the-hits?’ argument, and it’s an old one. We could have seen The Blockheads or Seasick Steve or MGMT instead. But I wanted to hear ‘Dying on the Vine’, ‘Fear is a Man’s Best Friend’, ‘Guts’ (“The bugger in the short sleeves fucked my wife” is one of the funniest opening lines), ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Afford to Orgy’, ‘Cable Hogue’, ‘Big White Cloud’ (and I think he missed a trick by not playing his haunted and aggressive version of Heartbreak Hotel). Nope, none of that. Ha-ha! Therefore, I didn’t get what I wanted. He broke my heart. And then I had to apologise to several friends I had dragooned into coming with me on the strength that he was a founding member of the Velvet Underground.

But the opposite later occurred. Hearing the new songs and rarer songs actually pointed me directly to his back catalogue and latest album Black Acetate, and now, rather than feeling like being left out of a party, where only the die-hard in-crowd know what’s going on, I had been pointed in the right direction.

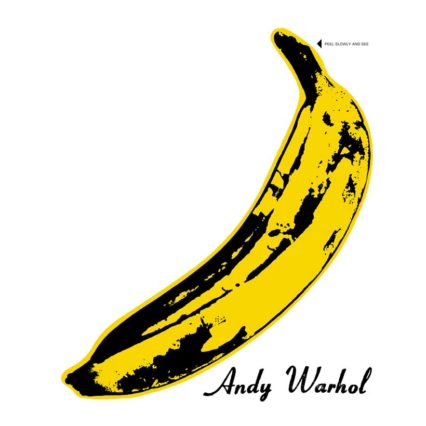

Yes, White Light/White Heat, in contrast to the Banana album, was even more poorly received, un-promoted, and the supporting gigs to promote it unappreciated. And yes, the Velvet Underground continued after John Cale’s departure. White Light/White Heat was an artistic turning point for both founding members. It was a big moment when Cale left – without his experimentalism, the band would become more radio-friendly, structured, have clear verses and structures, bridges and choruses, Velvet-lite.

And yes, although Cale had a head start, Lou Reed’s solo career took off faster. Reed’s second album, the Bowie-produced Transformer, would hugely out-sell John Cale’s Vintage Violence, a disarmingly radio-friendly and oddly hippyish album (the VU hated the west coast scene) bereft of the avant garde and La Monte Young and John Cage influences, and the prior obsession with drone. It is maybe interesting to note that when Cale and Reed met, Cale was a softly spoken Welshman, a classically trained musician with highbrow concepts of music theory, and Reed was an aggressively gay NYC rock ‘n roller with access to meds and shock treatment. Cale suffered a nervous breakdown at roughly the same age as Reed, but, despite that and other similarities, they were the opposites of each other, and in a Lennon-McCartney way filled in the other’s musical gaps. But apart, Lou Reed would go on to have a much more successful solo career with angry New York City-inspired songs. Cale’s lyrics adopted a more intellectual aesthetic and sonic perspective whereas Reed’s influence was more literary, more novelistic, 1st person narrative. Whereas Cale wrote almost impenetrable songs about Rene Magritte and wrote songs and interludes with French titles and hashtags, Reed was still further exploring seedy and nocturnal themes, from Berlin to New York, and was experiencing the commercial fame and notoriety. However, they both ended where they began: avant garde, and rock ‘n roll.

Bands sometimes soften up from their earlier material when the money starts coming in: the rough stuff starts to be retrospectively acknowledged, appreciated, some hits start to emerge, and then three albums later and they’re on the radio. John Cale left the VU at the right time, when they still had the integrity of a live band without excessive tweakery in the studio.

As a young growing musician, Cale suffered from TB, and the medication prescribed was laced with opium, sending him into fits of ecstasy and delirium. Cale would later reflect in his autobiography that his later heroin use and musical experimentation could be traced back to these events.

Cale grew up in a rural mining village called Garnant. Desperate not to lead a coal-mining life like his violent father, Cale joined the Welsh Youth Orchestra age 13, benefited from a private education and various scholarships and developed diverse interests in artists, writers, composers and philosophers who would influence his later work. Schoenberg to Stockhausen, to Karl Marx and Dylan Thomas, to Lonnie Donnegan and Bill Haley. Aaron Copeland even wrote a letter in support of Cale’s successful scholarship application.

In Cale’s candid autobiography (co-written with VU nerd Victor Bockris) What’s Welsh for Zen?, Cale shows the kind of risk-taking that would put him into contact with Reed. Cale cashed in his return ticket home and rented an attic, and to supplement his dissolute lifestyle sold heroin for La Monte Young, a celebrated avant garde musician.

At this point, Reed worked as a staff writer at a record label specialising in quick pop hits; his first song was a tune called The Ostrich, which coined a dance phase and gained a reasonable chart position. Upon first meeting, Cale was amazed to discover Reed had written The Ostrich and had used an open tuning whereby all the instruments are tuned to the same note, the very same approach Cale had been using with Young. Despite Reed initially playing his songs to Cale on acoustic guitar, which Cale found folky and drippy, he couldn’t help but respond to the literate, cinematic and novelistic lyrics. Collaboration with a classical musician from the avant garde gave Reed a confidence, a vindication. With Cale, he could really thrive. Both had an immense gift for improvisation, and jams at their shared flat would go on interminably, and making Sister Ray appear punchy by comparison.

Surprisingly, they had quite a lot of success as buskers, performing Reed’s songs in Harlem, but otherwise made money selling drugs. Lead guitarist Stirling Morrison joined Cale and Reed in 1965, and three of the four members were in place, but what to call themselves?

Within two years The Falling Spikes became Warlocks became the Velvet Underground (named after a 1963 novel about suburban wife-swapping) became The Velvet Underground and Nico became a third part of The Exploding Plastic Inevitable became The Velvet Underground. Despite early equivocations towards a collaborative environment – they were, after all, at The Factory – Andy Warhol soon lost interest in the band, and Reed’s infatuation dissipated. Cale felt Warhol was driving a wedge between him and Reed, and for a while he did. Things were moving fast at the Factory, the drugs, the constant parties, and Cale worried that, thanks for the publicity, but they were being dragged in the wrong direction.

Of the four producers and engineers who did all the work on the Banana album, the sole producing credit went to Andy Warhol, and only the Nico songs were written and recorded during the heady period of The Factory. Still, it would be wrong to deny Warhol made any difference. He gave his name, his money, encouragement, rehearsal space, and access to many weird and wonderfuls. And of course, that album cover, the cover of which doesn’t even mention the Velvets, simply: Andy Warhol. Andy didn’t interfere. As a producer he provided the brushes, paint and easels, and galleries in which to display their art.

Of the four producers and engineers who did all the work on the Banana album, the sole producing credit went to Andy Warhol, and only the Nico songs were written and recorded during the heady period of The Factory. Still, it would be wrong to deny Warhol made any difference. He gave his name, his money, encouragement, rehearsal space, and access to many weird and wonderfuls. And of course, that album cover, the cover of which doesn’t even mention the Velvets, simply: Andy Warhol. Andy didn’t interfere. As a producer he provided the brushes, paint and easels, and galleries in which to display their art.

John Cale had many complaints with the Warhol collaboration, and despite the knowledge that Nico’s involvement would be restricted to the Banana album, and with Warhol losing interest in the Velvets as an Exploding Plastic Inevitable act, Cale was adamant on creating a live album next. He said the Banana album did not reflect a live Velvet Underground experience, felt the Warhol album over-produced, many tracks converted from mono to stereo, much to the band’s insistence otherwise; some of the edges had been softened and there was a kind of loose tightness, quite the antithesis of their next album, White Light/White Heat (1968), a blast of swaggering underground mayhem, allegedly recorded over two crazy days.

White Light/White Heat is perfectly book-ended with the title track, and closing with Sister Ray. These bombastic songs help to capture what makes the contradictions within the Velvets’ sound: urgency, debauchery, immediacy and improvisation, and sonic experiments with three or four chords. Both songs create a sense of impatience, both tracks start before the beat, using a pick up note, or anacrusis, a musical term Cale would know, but which Reed would know instinctively. So the title track lurches to greet you, provides a more than adequate welcome-to-the-jungle declaration of intent; the call/response in WL/WH sounds almost like an argument between the id and the ego, the title referencing the dubious pleasures of amphetamine use. We are immediately prepared for a trip into a world of opiates and sex and dangerous hedonism, humour and sadness, nihilism and ecstasy, the laconic and the druggy loquaciousness.

There’s a great story about VU playing Sister Ray in its glorious 20-minute entirety. After the gig, the bar owner said if you play that song here again, that’s it. Therefore, the next time the VU rocked up for their 45-minute set, the only song they played was Sister Ray.

Cale supplied lead vocals to The Gift (a short story written by Reed at college, and using the groove to an unreleased song Booker T) and Lady Godiva’s Operation. I Heard Her Call My Name, a nihilistic song about sex and death, is the only song that could have been included on the Banana album. Reed also takes over some lead work from Stirling Morrison, with Morrison rightfully unhappy with Reed’s ability. Cale would go happily from thumping piano to playing a bass guitar with only two strings to screeching viola. Moe’s drumming was deliberately rudimental, but provided a constant, steady groove the others could relax into; steady and reliable, a bit like Moe’s other job: chief peacekeeper.

Despite rock apocrypha of the time, the album did not take two days to record but eight sessions over two weeks, which is still pretty impressive. The emphasis on this recording was of a sonic war, an ‘anti-beauty’, and resolutely the antithesis of commercial. “I wanted to fuck the songs up,” Cale would later recount. Moe Tucker called it a “constructed lunacy,” with the engineer telling the band, “all the needles are on red!” Do as best as you can, was always the response.

If not at all times, but this time especially, Reed was highly unpredictable and unreliable, and if not for his arguments and contradictions and heroin use, the band might have had a splendid time making WL/WH. Despite the collaboration between him and Cale, Reed would re-mix the tapes behind their back, claim full ownership of the writing and arranging and drive a wedge between him and the band.

But after Cale was fired, by Morrison under Reed’s instruction, a period of wildness left the band. The next album would feature ballads and nothing would reach the sonic pitch; and the ‘noise brings clarity’ argument that defined the first two albums was gone. I’m not sure who mitigated whom. Cale was certainly the musical director, adding form to Reed’s improvisation. In addition, Reed’s insistence on narrative reined back some of Cale’s wilder experimentalism. Cale called their relationship a non-sexual love affair that ran its course. Lou Reed, Stirling Morrison and Moe Tucker would be joined by Doug Yule, and continue as The Velvet Underground, and John Cale would start to plan for his solo career, and take a different path.

While Reed would pursue a more commercial path (the exceptions being Berlin and Metal Machine Music, a contract-fulfilling and musical fuck you to record label RCA) and even though Cale had a head start, both would flounder without critical or commercial success. Reed’s first album was a flop and he retreated to his parents’ house and took a job with his father. For Cale’s early years he produced and arranged albums for Nico, Patti Smith, The Stooges, and a lot of uncredited work for Nick Drake.

Both Cale and Reed would have their struggles with addiction, Cale first heroin, then cocaine, then booze. Reed would use heroin regularly but later got heavily into amphetamines. Cale was offered a record deal and A&R work and some producing in London. Cale saw this as an opportunity to get off the smack and upon his departure Bridget Polk of E.P.I fame saw him off but not before asking him to sing “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” on her tape recorder.

“Then wearily the footsteps worked

The hallelujah crowds

Too late but wait the long-legged bait

Tripped uselessly around”

But despite going solo, Cale and Reed would perform and record together infrequently, from Songs For Drella (1990), a memorial album for Warhol – his Factory nick-name (a portmanteau of Dracula and Cinderella), to various reunion tours.

There is a certain anarchy in collaboration; a sense of you-and-me-against-the-world. A kind of metallurgy takes place between people with disparate talents but a shared understanding; an essence is eventually extracted from the huge rock of sound and noise. You might well struggle as an artist without a sounding board, a team bereft of yes-men who will quite happily tell you exactly what they think.

The abstract expressionists of rock didn’t require approval, in fact they took great pleasure quoting bad reviews inside the sleeve of the Banana album and also on posters for gigs and promotional leaflets and press releases. They wore sunglasses at night, didn’t move about much on stage, and rarely acknowledged the audience or the EPI fanfare swirling around them. Arrogance and insolence are a niche market, but, by contrast, Television, who some claim took off from where the Velvets left off, saw their aloofness and self-confidence end their career.

It is hard to write about John Cale without mentioning Lou Reed. For their time they were the modern day American Lennon-McCartneys, who unfortunately for us, and unlike the latter, performed together for too brief a time.

Max Ashworth is a regular Wales Arts Review contributor.