St. David’s Hall, Cardiff, 4 May 2017

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Piano: Stephen Hough

Conductor: Xian Zhang

Tan Dun: Internet Symphony No.1 (Eroica)

Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody On A Theme Of Paganini

Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique

The BBC was wise to advertise this concert with the Berlioz Symphonie fantastique when they might have done so with its opening bagatelle – Chinese-American composer Tan Dun’s ironically titled Internet Symphony No 1 (Eroica) – or the still-galloping warhorse of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody On A Theme Of Paganini. The irony of Dun’s five-minute work is in the ‘heroism’. All three pieces are divertimenti in the sense that their manner is almost secondary to their matter, even in the Berlioz, with its ever-evolving pipe dream weaving its way tendril-like around a five-movement framework.

The decision meant that we could take the first work’s modernity as being more about the part played in its conception by digital media than about a truly contemporary piece in the musical, progressive sense. One might also say that its origins as a Google/YouTube commission, whose performance by around 3,000 auditioning ensembles in seventy countries led to the first outing at Carnegie Hall in 2009, were solely about internet reach. This is confirmed by its barely-sustainable claim to be interesting musically. It makes some initial noises to denote that it’s of the time, but before long the orchestra is galvanised to ride out on a tune whose banality is at best disappointing, at worst insulting. That Dun derives his use of the description ‘heroic’ from his view of the participants as ‘online heroes’ only further diminishes both the music and what one understands by heroism. We can all be heroes for fifteen – or five – minutes now, however debased the term. Perhaps it’s early days, but the suggestion that the mechanisms of the worldwide web can somehow transform or ease the basic elements of composing music – seclusion, inspiration, perspiration, and recognition – seems fatuous. And that its aim was to ‘invent a new era of classical music’ by passing on traditions and encouraging re-invention by the young, though laudable, seems even more insubstantial, when not meaningless.

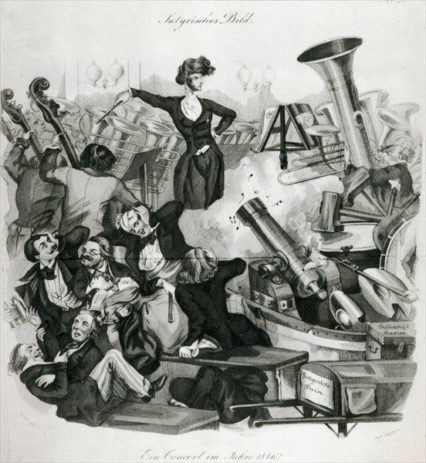

If Dun’s idée fixe in his work was the belief in cyberspace as the impetus for delivering socio-musical goods, Berlioz’s in the Symphonie was his muse, the Irish actor Harriet Smithson, denoted by what in opera are leitmotifs, and in the development of musical structures, ritornelli. Berlioz’s ‘returns’ to the theme, however, are not small of stature. Suitably transformed in the work’s every picturesque movement, they help the music burst out of its substructure; one as committed to Beethoven’s way with building blocks as it is to dissolving the continuity and concentration within the resulting framework. Though balance, orchestra numbers, and modern instrumentation would have been inhibiting factors, it was a shame that the BBC NOW couldn’t have turned up a couple of Berlioz’s ophicleides (instrument makers Wessex produce them) to replace the tubas played by Daniel Trodden and Martin Knowles, and to join the harps (Val Aldrich-Smith, Ceri Wynne Jones), bells (Andrea Porter), E-flat clarinet (John Cooper), and cor anglais (Sarah-Jayne Porsmoguer) in reminding us of how revolutionary this symphony was and how startling it still sounds, even after long assimilation of its procedures.

Perhaps the appearance on the rostrum of the orchestra’s principal guest conductor, Xian Zhang, was partly responsible for inclusion of the opening work. Having steamed through that, she set about solving the problem for all orchestras performing the Symphonie – that of defining some kind of border and perspective for all the darkness and devilry. It wasn’t a bad effort all told, the direction as sure-footed as the scene-painting; the narrative of the third and longest movement in particular benefiting from sharp and extended focus, but not at the expense of what had preceded it and what was to come. The ballroom scene of movement two could have withstood a more leisurely sliding of pitch to emphasise its wistfulness, but the march to the scaffold of the fourth movement was a genuinely scary dreamscape. There was more horror to come in the final parade of grotesquerie, with Cooper’s E-flat clarinet to the fore in vilification of the idée fixe. The fun of playing this music, of course, lies in the realisation that, even in the version for large modern orchestra, what one gets is probably not half as eerie as what was going round in Berlioz’s head. That said, the performance was spirited, the only reservation being the achievement of some slight fudging of tempo and texture at the expense of pointing up the shadows, the shocks and the awe.

By contrast, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody is a model of delicacy and passion under control, especially so in the hands of a pianist such as Stephen Hough, who has had a lot to say, not all of it convincing, about how the composer’s piano concertos should be considered. In this performance, he was almost leisurely, with hints of the rubato encouraged by a relaxed keyboard manner just about incorporated by Zhang into the overall scheme, while she was concentrating on preventing any slide into heavy-handedness among her players. There were some lovely solo efforts and some insistent changes of pace that almost always chimed with Hough’s barely-concealed attempt to dictate the course of events, notably in the famous 18th variation. Zhang and leader Nick Whiting clearly felt that the more urgent episodes should not be infected by Hough’s cool demeanour, a mood that skirted stasis in his soft-centred and languorous encore, Debussy’s Clair De Lune.

This concert was repeated at the Brangwyn Hall, Swansea, on Friday, 5 May, where it was recorded for broadcast on BBC Radio 3 (now available on iPlayer).

Header photo of Xian Zhang (c) B. Ealovega

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.