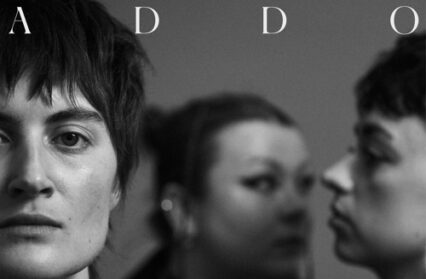

Nigel Jarrett unpicks Welsh National Opera’s latest production of Bizet’s iconic opera, Carmen.

One of the problems of trying to confound expectations in music-theatre is its capacity for encouraging regret and longing. Many opera-goers want from Bizet’s Carmen, set in Seville, sunshine as piercing as a banderilla or the atmosphere emanating therefrom. Add the story’s passion and they’re glad to be sitting in an air-freshened auditorium, with a drink to come at the interval. In weather terms that’s the Spain of the travel brochure and they’re happy with it. But stroll into a Spanish city’s zona industrial or its neighbouring back streets and any holiday takes on the appearance of having been mis-sold. They don’t go there; but the excellent Jo Davies, director of WNO’s new production of the opera, and her team do – sort of. Are the audience’s regret and longing any less justifiable? Ancient or modern, Carmen‘s geography will always be foreign.

Photo Credit: Bill Cooper

For a start, the heat and colour are in the music, or as much of it as is in the gift of conductor Tomáŝ Hanus to generate with his orchestra. Even if sets (Leslie Travers) and costumes (Gabrielle Dalton) were rendered in monochrome, the atmosphere would still be stifling. It doesn’t even dissipate when we discover that Davies has wandered into a variation of the original locale. She transforms the opera’s soldiers and gypsy-smugglers into repressive troops and gun-running revolutionaries, taking inspiration from the Brazilian military and its uneasy relationship with the inhabitants of Rio’s slums – the favelas – and the attempt to raze them. In the programme note, always essential reading in opera houses today, she seeks to explain the character of Carmen in terms of the situation in which the woman finds herself, from both the traditional ‘non-feminist’ viewpoint (the given) as well as the contemporary one in which the distaff side is defined and ‘explained’ by men’s boorish and aggressive behaviour towards it. That such attitudes are still widespread goes almost without saying. But Davies’s clear vision of the opera is not even remotely Weinsteinian.

Photo Credit: Bill Cooper

The new criticism finds no objection except among the inveterately unenlightened, who probably don’t go to the opera anyway, an important point to make when the attitude of Carmen‘s 1875 audiences is considered. But Davies makes a slightly fatuous comparison between Carmen, the loud, full-on, femme fatale, and Jane Goody, the loud, full-on, contestant in the TV programme, Big Brother. Dumbing-down and Goody’s courageous but losing battle against cancer aside, it’s conveniently forgotten that she also and infamously dished out loud and full-on racist abuse to another Big Brother contestant, though bizarrely denying it (much as Donald Trump denies telling a lie when he has told a lie). Despite the gender and social contexts – Goody was the working-class daughter of a drug addict and a pimp; this Carmen lives in a dump but has some taste – few can afford to make excuses for bigotry, or for that matter any other misdemeanour, though they all have their provenances. Loud and proud; loudly proud and nasty; or shameless, gobby and racist? One piles it on if only to question what this issue has to do with Carmen the opera or Carmen the woman. Who today takes against Carmen? If anything it’s Don José who has always been the weak and pathetic no-hoper, afraid to withdraw from the scene and seeking a resolution of his fateful fantasies in violence. He’s pure boo-hiss. That was as true at the Opéra-Comique in Paris 144 years ago as it is today. Only public opinion was/is different. We might have changed a bit, but few opera buffs in £50 seats in 2019 would ever wander into a Brazilian slum, or expect to find anyone seemly inside it. That’s what the class angle is about.

Also in a programme note, Clair Rowden refers to the ‘unenviable task’ of once more presenting Carmen as an ‘entertainment’. Come again? ‘Entertainment’ used in this sense means innocent diversion (otherwise, why draw distinctions?) and the corollary that opera-lovers are party to it. We don’t sit through Otello, The Ring cycle, Eugene Onegin – or Carmen, the place of its première notwithstanding – for amusement; but it’s our loss if we see them as irrelevant to our lives. Davies’s Carmen is a thought-provoker without being over-wrought. It’s processional evenness – with some super table-top dancing (Josie Sinnadurai, Carmine De Amicis) in the tavern scene, the whole choreographed beautifully – is matched by an equivalent balance of casting and musical delivery, departments in which opera companies so often get Carmen wrong. A good example is Phillip Rhodes’s Escamillo, here not entirely centre stage in the scene where he delivers his ‘Toreador Song’ as part of a smartly devised movement full of other incident.

Virginie Verrez’s voice in the title rôle needs no encouragement. Her way with some of the most familiar stand-alone tunes in opera is sound and assured if at times revealing places where further experience should lead to a more clearly etched portrayal. Davies directs her as someone less than impulsive, which makes another welcome change. Dimitri Pittas’s Don José is a lost soul from the start, as are his fellow squaddies, if body language is any guide. But both he and his hapless platoon sing so convincingly that we listen with more profit than we look. Unavoidable but eminently serviceable is Travers’s set: a curved cement backdrop that triples throughout as, respectively, tenement, derelict building (no mountains here) and outer bullring. The soldiers, armed with assault rifles – everyone on stage appears to possess a weapon – seem too inactive for their own good in what’s supposed to be an incendiary place; as the original barracks loafers they’d be fine, minus the gun-toting. Don José’s ambivalence towards Anita Watson’s admirable Micaëla, for which she summons the appropriate vocal resources, makes her character even stronger. There’s strength, too, in scenes that are sometimes dwarfed by the opera’s Big Moments, the ensemble singing involving Frasquita (Harriet Eyley), Mercédès (Angela Simkin), Remendado (Joe Roche) and Dancaïre (Benjamin Bevan), for instance, dazzlingly accomplished. Henry Waddington gives the bel officier Zuniga bulk of voice and physique, and Ross Ramgobin as Moralès makes the most of the little Bizet offers him. The tenement children – Emilia Campion, Mia Cocchiara, Isabella Davies, Guto Peredur Jenkins, Eiriana Jones-Campbell, Peter Martin, Nathan Marytsch, Matilda Mae Morris, Harriette Roberts, Luke Samra, Alys Thomas, Heidi Warren and Osian Twm William perform like troupers.

Photo Credit: Bill Cooper

Davies has delivered an interesting concept. But is it an illustration of what the critic Ernest Newman meant when he described Carmen as the most Mozartian opera since Mozart? Much of the orchestra playing enchants and the chorus again gives everything a sense of concentrated purpose. It’s more of a start than we are routinely offered, despite Davies’s insistence that we should re-compass our bearings.

Information on the current tour of Carmen can be found here.

You might also like…

Gemma Pearson experiences one of the projects attached to the Garth Evans residency in Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff, The Cardiff Tapes, a Chapter and Everyman Production.

Nigel Jarrett is a former newspaperman. He is a winner of the Rhys Davies prize and the Templar Shorts award for short stories, and is represented in the Library of Wales’s anthology of 20th– and 21st-century short fiction. Among others, he writes for Acumen poetry magazine, Jazz Journal, and on music and other subjects for the Wales Arts Review. His pamphlet of stories, A Gloucester Trilogy, has just been published by Templar Press.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.